by Cate Smierciak // Nov. 3, 2011

Opening Reception: Tacita Dean’s film at the Turbine Hall at The Tate Modern. Photo by Beda Mulzer

Opening Reception: Tacita Dean’s film at the Turbine Hall at The Tate Modern. Photo by Beda Mulzer

Walking into the darkened Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern, one is drawn by a soft flickering across the room. Approaching this glow – its source initially blocked by a large structure behind a staircase – a huge, vertical screen comes into view, pulsating with rich, vivid images from a 35mm projector. Dean has turned the hall into a giant cinema with her work “Film” for this year’s Unilever Series.

The piece, an 11 minute film loop projected onto a stunning, 13 meter high surface, is Dean’s tribute to film – a medium increasingly endangered by the democratization of digital technology, the increasing expense of film stock and post production, and rapidly closing labs and equipment rental houses.

The piece, an 11 minute film loop projected onto a stunning, 13 meter high surface, is Dean’s tribute to film – a medium increasingly endangered by the democratization of digital technology, the increasing expense of film stock and post production, and rapidly closing labs and equipment rental houses.

An image of the Turbine Hall itself serves as a background for much of the film, consistently flanked by what seem to be sprockets, or the holes on the edges of a piece of film used to pull it through a camera or projector.

Sections of the hall are often turned on an angle, tinted with a bright color, or simply replaced with a plain color field. One image, a large yellow circle, is an homage to Eliasson’s Unilever commission (They are studio neighbors here in Berlin).

Images of nature, Deans eye, that of her son, Rufus, and a hand-painted mountain are among many that have been “overlayed” onto the Turbine Hall background. The mountain is both a reference to René Daumal’s book, Mount Analog, about a mountain that can only be reached by those who believe in it, as well as a wink to Paramount Studios’ logo, simultaneously affecting Romanticism and nostalgia.

“I’m in no way anti-digital,” Dean says “…it’s a fantastic medium that’s got massive potential.” She loves film, rather for its unique materiality, its specificity, explaining that she “needs the stuff of film as a painter needs the stuff of paint.”

I personally had the honor and treat to work with Dean on this project, as a camera technician here in Berlin. It was thrilling for me – likely of the last generation to be taught on film – a lover of process and material and handling, to help Dean tackle the kinds of technical problems few have faced since the 1920’s.

At the exhibition, the viewer is presented with a very large scale, impressive experience, named, someone in elegy, for the medium it celebrates, but many don’t realize the level of process involved in the work.

The only post-production done was a simple chemical hand tinting at one of the last remaining photochemical labs in Europe, and Dean’s long hours at a Steenbeck– an editing machine with which she physically cuts and edits physical film – as in, with a blade and clear tape – here in Berlin.

The effects in the piece, including the images of “sprockets” that run continually along the sides of the images, were created using very old, in-camera techniques, pioneered by the likes of Georges Méliès and Norman Dawn in the early 1900s.

Needless to say, we were presented with some unusual challenges.

Each piece of film had to go through the camera a number of times, ranging from three to about ten, in order to complete the full-frame image. Additionally, the magazines holding the film often had to switch from one camera to another in order to complete the picture.

Keeping track of what material was shot on which portion of the frame, in which place on the roll, on which roll of film – was an organizational feat demanding quite a bit of concentration and a custom logging system. Even wrapping your head around that sentence might take a second read.

Additionally, camera teams receiving partially shot film had to find the exact sprocket, or hole in the film stock, to be engaged by the mechanical pin that pulls the film through the camera when beginning their own shooting. This was the only way to shoot and mask off the correct portion of the filmstrip. Marking and understanding this meticulous type of loading is the only way to achieve multi-camera multiple exposure tricks without the help of postproduction.

A potpourri of other analogue tricks were used on the project, including glass painting, DIY color filters, and the unique use of an anamorphic lens in portrait format.

Dean has often worked with this sort of lens. Usually used in landscape format, it produces very wide, dramatic images. Dean decided to literally turn the lens 90 degrees to create a vertical, or portrait format image with striking proportions.

She says this was the first decision she made about the project, standing on the bridge of the Turbine Hall upon receiving the commission. Utilizing the grid structure of the architecture of the room itself, Dean uses the iconic space to create a portrait of the filmic medium.

The conversation about film disappearing from the market, the cinema, and the artist’s palette is an emotionally charged one, both in the museum and in Hollywood. The work’s accompanying book, edited by Nicholas Cullinan, includes insight from artists, feature film directors, and even actors, all extolling celluloid for its unique aesthetic, the specific meaning it gives to their work, and its current melancholic swan song.

ON THE SAME DAY that Tacita Dean’s show opened in London, Birns & Sawyer, the longest-operating camera rental house in LA, announced they would be auctioning off their 16 and 35mm film Camera inventory. In recent years, labs have closed and stocks have been discontinued. But Film is not dead yet.

Many feature films, and even some television programs, are still being shot on celluloid. That said, the market is certainly shifting, and proliferation of digital photography is making film processing more expensive – if only because this work is becoming more “specialized” as opposed to the standard it used to be.

Those who love grain and mistakes and the warmth of film – those who enjoy the process as much as, or even more than the final product – they will hold on for some time. Someday, film may become an old-fashioned delight, as the analog tricks in Dean’s work were for her and her crew.

But hopefully, at least a few of the film cameras that will be auctioned off by rental houses in the future will be bought by people who intend to use them. Not just to display as a collectors item, but to make new work, expose new film, keep some labs making and developing stock. Keep the industry going – and keep Dean busy making films.

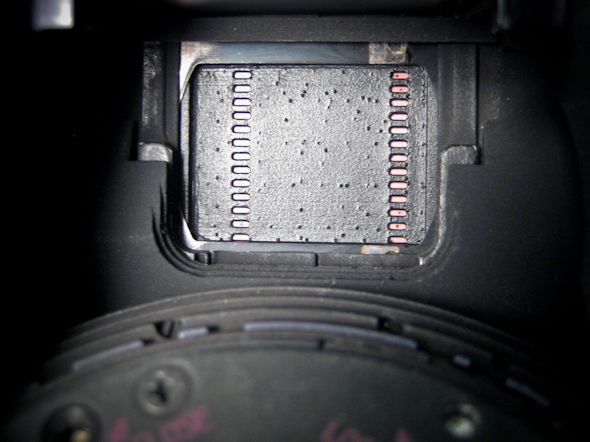

One of the custom-made masks used in the camera to create exposure effects. This one made the white sprocket holes on the edges of all of the footage. Photo by Johannes Thieme

One of the custom-made masks used in the camera to create exposure effects. This one made the white sprocket holes on the edges of all of the footage. Photo by Johannes Thieme

Homemade color filters to tint the image. Each portion of the final image that is tinted a different color shows one pass of the film through the camera, with the rest of the image masked out. Photo by Cate Smierciak

Homemade color filters to tint the image. Each portion of the final image that is tinted a different color shows one pass of the film through the camera, with the rest of the image masked out. Photo by Cate Smierciak

___________________________________________________________________________________

Additional Information

Tacita Dean was born in Cantebury in 1965. She lives and works in Berlin.

TATE MODERN

The Unilever Series: TACITA DEAN

Exhibition: Oct. 11, 2011 – Mar. 11, 2012

London, UK

___________________________________________________________________________________

Cate Smierciak creates and writes about film, video, and photography in Berlin. She received her BA in Radio/Television/Film at Northwestern University, participated in the FAMU International program in Prague, and spent a year at the HFF Potsdam-Babelsberg on a DAAD Artist Study Grant.