by Jessyca Hutchens, photos by Song-Ming Ang

Although all art is ostensibly concerned with originality, the music world is kind of obsessed by it, still. The most lauded musicians or bands are seen as a having a trendy set of ‘influences’ (which in no way detracts from their originality), while the most derided are seen as purely derivative. It is on this basis that pop music has been traditionally criticized; it relies too heavily on the familiar, the catchy refrain, to be seen as truly original. Song-Ming Ang made music before he was an artist. As an experimental laptop musician, Song-Ming eventually felt that he was only emulating accepted styles. He chose instead to create art about music; an approach he felt could actually be more experimental, while still indulging his love of music. His experimental approach now, is applied not just to discrete musical genres or artifacts but also to the codes and conventions that shape our understanding of music. In my experience of his works, I saw notions of originality and authenticity at their core. To be experimental is not always to be original but, like pop, it can help to make a fresh start on old ground.

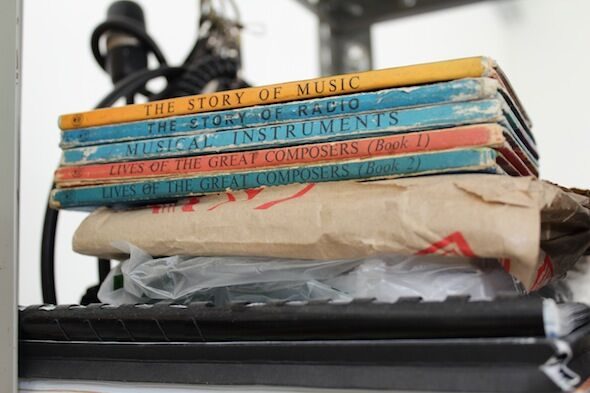

When I walk into Song-Ming Ang’s studio at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien (where he was a resident for one-year until very recently) the music-art connection is hard to miss. Something upbeat is playing from laptop speakers; glancing around the room I pick-out an Alvin Lucier book and a Justin Bieber poster among other music paraphernalia.

Parts and Labour” (2012), video

The first thing that Song-Ming shows me is a piano, a perfectly ordinary-looking working piano that, he explains, has been completely disassembled and then reassembled by him. I play a note. It’s in tune. The work,

Other recent labours are hidden in plain sight around the studio. Scrawled across the glass windows in pastel pens are Song-Ming’s “practice versions” of Justin Bieber’s signature. The work Justin (2012) includes practice sheets made over three-months, and a final perfected autograph on a Bieber poster. Here the labour in the forgery could translate simply – it’s not as easy as it looks to be Bieber. The slick one-dimensionality Bieber is most often scorned for, embodied by his literal autograph, is given a labour-value by Song-Ming. And it is Song-Ming’s forgery that is fake – not the sweet smiling, neat-haired pop-idol himself. The Bieber persona may be comparatively, well, real.

“Piece for 350 Onomatopoeic Molecules” (2012), video

On another wall I notice a series of minimal watercolour paintings aligned above a corresponding series of vinyl records. The works, Stop Me If You Think You’ve Seen This One Before (2012), made me do, well, exactly that – I was adamant that I’d seen them before, only to be assured that that they had never been exhibited.

What I had seen was a Jonathon Monk work that has been closely appropriated, down to the frames, to make this one. The central difference being, that Jonathon Monk’s work uses Smith’s records while Song-Ming’s work uses Belle and Sebastian records – a band heavily influenced by the former, both in their musical style and overall aesthetics (Song-Ming points out how both bands often used monochrome photographs for record covers). In the same way that Monk himself gets accused of making arty witticisms, does Song-Ming do the same, only adding an additional layer to the in-joke? But then the musical inter-textuality that Song-Ming produces here is also what he deconstructs across various works. And I think what takes this work, Justin and Parts and Labour beyond the one-liner effect, is the role Song-Ming is playing. He acts almost as a master forger- hiding his efforts and labour in the art objects he produces (the perfect piano, the perfect signature, the perfect appropriation), while letting his audience in on the secret.

Before this last year at Bethanien, most of Song-Ming Ang’s work incorporated a more literal social dimension, often engaging the audience in direct participation. An early work, Piece for 350 Onomatopoeic Molecules (2003), entailed a room full of live electric guitars, coloured plastic balls and an active audience. A 2010 work made during a residency with ARCUS Project, Japan involved Song-Ming inviting a group of former students of an elementary school, to remember their school song long after graduation.

The video work Be True To Your School (2010), shows the participants as they struggle to accurately sing the song (it’s fascinating to see and hear how their voices track the process of remembering), as well as a final performance by the group after they have been given access to the complete words and melody. As with Parts and Labour, there is a sort of disarray before order is then restored. The final song comes across as oddly satisfying, while the half-remembered versions convey something more of nostalgia. Again, Song-Ming’s strength lies in contrasting two musical versions in a way that confuses categories such as, original/copy, authentic/contrived.

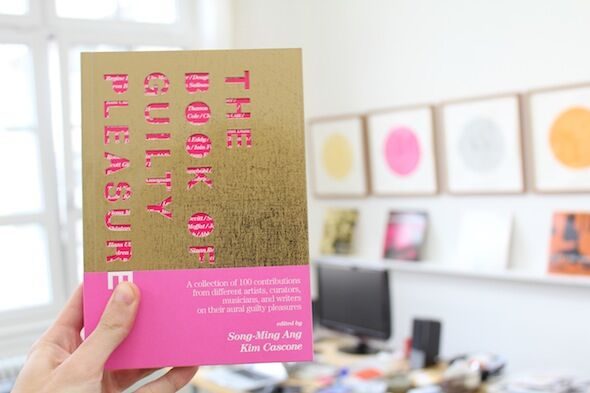

In Guilty Pleasures a work which began as a series of listening parties (the first taking place at in 2007 at the Singapore Art Museum), Song-Ming invited participants to bring along and share with others an audio guilty pleasure. The work then evolved into The Book of Guilty Pleasures (2011) co-edited with Kim Cascone, where a variety of curators, writers, artists and musicians were asked to contribute a text and image on the topic. Surprisingly there are not as many cheesy pop “choices” as you might expect, with that already being an expectation of sorts and therefore not so guilt-inducing.

“Be True to Your School” (2012), video

As the artists Aeron Bergman and Alejandra Salinas write; “artists are supposed to love pop music and trash culture as an antidote to our normally (so called) elitist activities.” (p. 21) There is of course, the danger, that a work like this might only reproduce a music culture where it is increasingly hip to have the right bad-tastes. But the diversity of opinions, at least in the book, suggests this is still a question worth asking. While Song-Ming’s aim may seem to be to try and democratize the playing field, his real achievement is ever to reveal the very complex system that we have in place to simply decide what we like to listen to.