Article by Marta Jecu; Tuesday, Jul. 21, 2015

The following series of interviews look at the curatorial work within three pavilions at the 56th Venice Biennale. Though in different ways, the exhibition spaces in these pavilions are not understood as a mere container or receptacle of artistic pieces. They are designed to create a context, inducing meaning in the work or even co-formulating its reading. The usual exhibition space as a temporary platform that displays a certain content is being annulled here, while it instead becomes a sort of agent of the work. In an almost uncanny way – which duplication or mimesis usually causes – space is delegated to materialize a discourse, situating the works in a particular tradition and instantly immersing the viewer in it. In the following conversations with the curators of these pavilions, we will not explore so much the artworks as their thoughts behind these contexts that the architectural spaces bring forth.

The curatorial approach of the exhibition space will be followed in interviews with Mihai Pop, the curator of the Romanian Pavilion, showing the work of Adrian Ghenie; curator Katya Garcia-Anton, showing Camille Norment in the Nordic Pavilion; and in a discussion with Nina Magnusdottir, who curated the Icelandic Pavilion, transformed into a functioning mosque by Christoph Büchel.

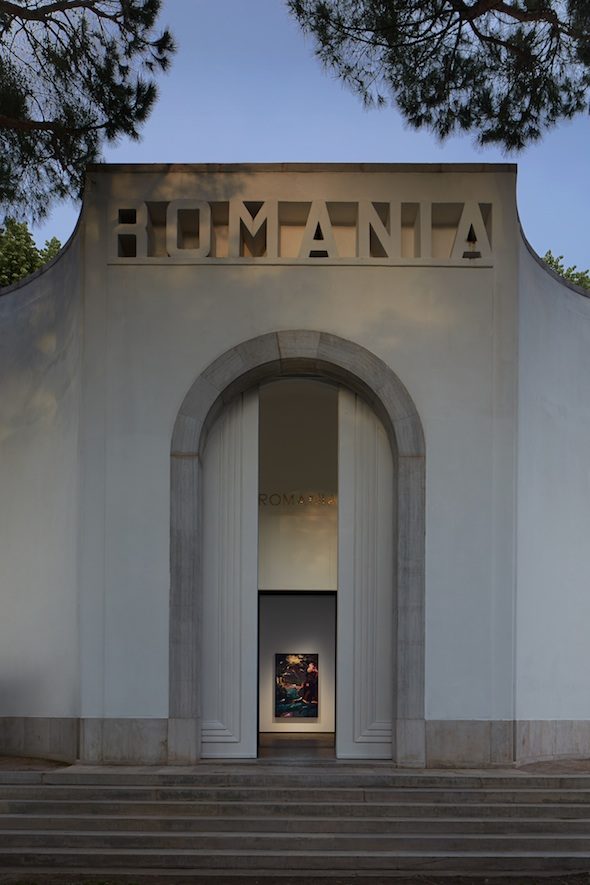

Romanian Pavilion, Entrance, Installation View; Photo by Mathias Schormann, Courtesy of the Romanian Pavilion

Romanian Pavilion, Entrance, Installation View; Photo by Mathias Schormann, Courtesy of the Romanian Pavilion

Entering the Romanian Pavilion we are instantly immersed into the prototype of a museological situation. Five generous exhibition halls appear unexpectedly in what had been, for decades, played out as a unitary space. The walls are heavily charged with the immense paintings of Adrian Ghenie. The impact is strong, imposing and coherent. While admiring the works, a classic ‘Salon’ display tradition reverberates. Adrian Ghenie is a so-called abstract symbolist, expressionist, deconstructor and re-appropriator. He flashingly became one of the world’s best selling artists. Together with Victor Man, Mircea Cantor, Serban Savu, Ciprian Mureşan, Cristi Pogăcean, among others, he aggregated what was called the Cluj School: a generation of artists of a Romanian post-communist cultural reality, that rose to prominence in 2005 along with the coagulating gallery PLAN B, with branches now in Cluj and Berlin. Its founder, Mihai Pop, is the curator of this year’s pavilion. I talked to Mihai Pop precisely about the implicit museological narrative that his curatorial approach and the particular display convey. Reinforced by a paradigmatic situation of contemplation – the viewer in an predefined position in relation to a slightly dominant work – these paintings are shown as incarnating a model of representativity, of historically accumulated and stored value. In a museological paradigm, the curatorial approach creates a subtle liaison between the affirmation of legitimacy given by a national context, a pictorial tradition in Romania, archived, but distorted under the constraints of the communist regime and the personal pictorial vigour of Ghenie.

Marta Jecu: This small interview is concerned with the curatorial discourse that you had in mind and its outcome on the architectural space.

Mihai Pop: As you have probably noticed there is no painting exhibition in the biennial, painting seems almost a rejected media, unfairly, because painting is very present in the world of art.

I was interested in a mature approach. We are part of a generation that, as I see it, reached a certain maturity. We are in what is called a mid-career situation: we did not want to play with this pressure of visibility and with the pressure of being ‘modern’ in the sense of ‘vanguard’ and ‘experimental’. For me the objective was to show in a mature way that which Ghenie’s painting represents, the historic content of his work, as he is approaching painting from this historic perspective. I see his work as having affinities for example with the German academic expressionism.

Adrian Ghenie – “Pie Fight Study” (2012), Oil on canvas, 55.5 x 76 cm; Courtesy The Sander Collection, Darmstadt

Adrian Ghenie – “Pie Fight Study” (2012), Oil on canvas, 55.5 x 76 cm; Courtesy The Sander Collection, Darmstadt

MJ: The display was therefore meant to place Ghenie’s work in a historic continuity of painting?

MP: I did not want to create a false historic legitimation. I just wanted to clarify what his painting is. Many people know his name, know his prices (as the market invaded his life without allowing a natural time frame of growth, which would have been necessary). Nevertheless many people do not actually know his work. Ghenie is an artist whose work is definitely entitled to be shown in Romania’s pavilion, but I wanted to give first of all weight to what this person is preoccupied with. We definitely could have created something more experimental for the Venice Biennial, but my intention was to clarify his work through a very consistent exhibition.

A main curatorial question was to find the perfect architecture for these works. As Ghenie is preoccupied with history, it became very interesting to look at the history of the pavilion itself. Looking at the way it was initially constructed, the architect Attila Kim and I understood that it must have been constructed on three divisions.

MJ: Where did you find the original plans?

MP: We asked Daria Ghiu, who wrote her PhD on the history of the pavilion and she told us that between 1938 and 1962 the pavilion had three inner spaces. In 1962 a big refurbishment was done and they created a new, unitary space.

As painting requires its own tempo of viewing (looking again and again), it needed a more labyrinthine space, since painting cannot be grasped just from a single viewpoint. When these pavilions were first built they were designed as an ‘echo’ of a museologic space. We wanted to confer back to the space its initial elegance from the time when it was built. So we brought to the surface a very beautiful Venetian tile floor that had been hidden by layers and layers of paint which were added by many generations (including mine, in 2007, when I was commissioner of the Romanian pavilion with the curatorship of Mihnea Mircan).

What we also did was reconstruct the walls and take down to the brick all the layers of wall paint which had been there. The idea was to see the space in relation to its own history and its own spatial model, which is a museological one.

Romanian Pavilion, Installation View, 56th Venice BIennale; Photo by Mathias Schormann

Romanian Pavilion, Installation View, 56th Venice BIennale; Photo by Mathias Schormann

MJ: Was the recreation of the pavilion to its historic form part of your initial project or did it occur during the process?

MP: It was part of the initial project. Corresponding to the three main divisions in the pavilion, for me it was very important in the case of Ghenie’s painting to delimit in space also three fundamental themes in his work: the tempest, portraits gallery and historic dissonances.

Painting has its own limitations regarding the amount of historic content that it can carry. If you put too much and too explicit historic content in painting, it becomes an illustration and you loose the painting.

In the classic painting masters, nature is always reflecting back to the subject of the painting. In a similar way, nature in Ghenie’s painting becomes also a metaphor for history and its tumults. So I have stressed these sub-themes that adopted the historic content of the paintings. In one of the paintings, ‘Opernplatz’ (which recalls the Nazi book-burning campaign that culminated in 1933 on the Opera square in Berlin), the largest part of the painting consists of a stormy sky, painted in an expressionistic ‘wild’ way, while it also carries the whole historic content without becoming illustrative (the legend goes that the storm and rain were so strong, that the books could hardly be burned).

MJ: You regard this historic non-illustrative way as a general working method of Ghenie?

MP: Yes, and this is also imposing a limitation to a curator, since anyway a solo show does generally need less curatorial input. But it probably needs a clarification of the material and this is what I opted for as a curator with these three themes and the corresponding spatial inner divisions.

Adrian Ghenie – “Carnivorous Flowers” (2014), Oil on canvas, 42 x 52 cm; Private Collection, Denmark

Adrian Ghenie – “Carnivorous Flowers” (2014), Oil on canvas, 42 x 52 cm; Private Collection, Denmark Adrian Ghenie – “Turning Blue” (2008), Oil on canvas, 30 x 31.5 cm; Courtesy of Collection Cooreman

Adrian Ghenie – “Turning Blue” (2008), Oil on canvas, 30 x 31.5 cm; Courtesy of Collection Cooreman

MJ: You have seen these themes as specific keys to read history in Ghenie’s work?

MP: Yes, and we included them in this sort of historic cabinet (or cabinet of historic curiosities): Darwin’s Room. For Ghenie, Darwin is a patron of the history that we share today, with him the paradigm changed. Ghenie says that if we look behind Freud or Marx‘s shoulder, we still see Darwin. Ghenie sees Darwin as an absolute figure of the modern world.

MJ: At the same time it seems to be a contradiction between the crepuscular, dim matter of social subconscious in Ghenie’s paintings and the clear, historically legitimated space of display: a gap between content and container which generally speaking contemporary art tried to overcome.

MP: The exhibition space is also meant for expressing a conservative side of his paintings, a sort of expressionistic academicism. I am thinking at this point about a painter like Max Lieberman or other central European painters from that same epoch (with their academic reflexes and historic references in a tumultuous expression.) This is where I would situate Ghenie and this is a rare approach, which is endangered to disappear: I was also drawing my curatorial approach from this insight.

MJ: Which other curatorial references in contemporary art come to mind from this point of view?

MP: While we have been in Venice, we went to Accademia to see how Tintorettos are displayed: the paintings all stay next to each other, charging themselves mutually. This type of display can also be found in contemporary artists like Cy Twombly for example.

Our exhibition is not a blasphemy, we did not intend to historicize artificially, but rather to access something which is intrinsic in the painter’s approach.

Massimiliano Gioni told me that our exhibition is one of the few pavilions that can be called ‘exhibitions’, while otherwise he had seen in many other pavilions works simply thrown into the space, ideas that have not been distilled until the point in which you can say this is a coherent exhibition: a coherence between the material and the presentation setting.

Romanian Pavilion, Installation View, 56th Venice BIennale; Photo by Mathias Schormann, Courtesy of the Romanian Pavilion

Romanian Pavilion, Installation View, 56th Venice BIennale; Photo by Mathias Schormann, Courtesy of the Romanian Pavilion

Personally I really appreciated the last Romanian pavilion and the way choreography filled the space*. So now I wanted to catch up with that and show that through these almost opposing approaches, Romanian art is a mature enough scene to be able to support diverse approaches.

At the last exhibition at Plan B for example, my curatorial approach was very different, literally opposite to this one in the Pavilion. These are different points of view at which I am working right now and choosing the most clear format for each of the artists.

I also think that the courage to exhibit painting in the most purified or essentialised way at the Venice Biennial is on one hand more eccentric than inventing another experimental approach. This could have been the case: conceiving for example an installation with his paintings – an approach that Ghenie had had before. I see the present pavilion as a risky exhibition, but I see it as being necessary.

—————

* At the 55th Venice Biennale, Alexandra Pirici and Manuel Pelmuş presented An Immaterial Retrospective of the Venice Biennale.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Additional Information

LA BIENNALE DI VENEZIA

“All the World’s Futures” – GROUP SHOW

Exhibition: May 9 – Nov. 22, 2015

___________________________________________________________________________________

Marta Jecu is currently researcher at CICANT Institute, Universidade Lusofona, Lisbon and independent curator.