Apichatpong Weerasethakul, or “Joe” as he’s known to most fans, grew up in a hospital. The child of two Thai doctors, Weerasethakul spent most of his time surrounded by the colors, odors, and rituals of this site of transformation, the origin of birth and often the backdrop of death. He calls hospitals “microcosms of humanity.” On the occasion of his first full retrospective years later, this term is equally fitting to describe the poetic, transformative works of cinema that capture his homeland.

‘Mysterious Objects at Midnight’ at Volksbühne is the culmination of a lifetime of Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s work thus far. In addition to screenings of popular films, such as ‘Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives’ (which won the Palme d’Or at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival), and rarer features, such as the 2-minute ‘Nokia Short’ recorded on a mobile phone, Weerasethakul also presents a new experiment with theatre. Concurrently, ‘Fever Room’ charts new territory for the filmmaker, in which audiences seated on the Volksbühne stage experience the dream-like materiality of cinema through a performance of moving screens and projected light on their bodies. Berlin Art Link spoke with the acclaimed director about his retrospective, the Berlin premiere of his theatre work, and the tactility of cinema.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul // Photo by Anna Russ

Jack Radley: Congrats on your first full film retrospective, ‘Mysterious Objects at Midnight’, here in Berlin. What does it feel like? What was it like looking at old work in preparation for this, and what have you learned from your archive?

Apichatpong Weerasethakul: It’s so nostalgic in a way because there are so many things that I have done and collected, but at the same time, even though there’s so many changes through the years of different kinds of camera formats, they are very much in the same universe because as a Thai person, I really only document my surroundings and the things that I love. The things that I would miss if they disappeared: my dogs, my boyfriend, my trees, rivers, certain actors who are friends. So I shot them.

JR: I know you have your own production company, ‘Kick the Machine’, which you brought here. Where does that name come from?

AW: It’s from a screening program in the early 2000s. I was part of this alternative space where I was in charge of the cinema program, and we go “Ok, let’s go kick the machine!” It’s an action that is anti-establishment, or it could simply mean to turn on the projector.

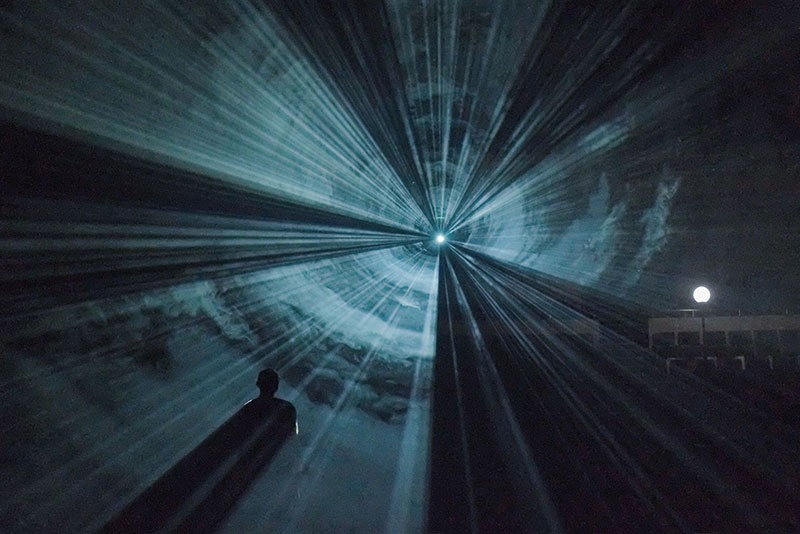

Apichatpong Weerasethakul: ‘Fever Room’, 2017. // Photo: Kick the Machine Films, Courtesy of Volksbühne

JR: With ‘Fever Room’, how do you think about creating a work of theatre vs. a work of film?

AW: It’s an accident. I never understand theatre – I watch and it’s so far away, I need a close up. But then with the challenge from the art theater commission in Korea, the curator loves cinema and challenges filmmakers to use theatre as a space. For me, my first reaction is “I don’t know. I only want to make cinema” so I look at a space and the view from the stage: it’s something new.

JR: I know you studied architecture, and I felt a real sense of space in ‘Fever Room’. The screens create a closed area, and the curtain lifts and it hits you that you are on the stage and you see the empty seats in front of you. How do you think about space in theatre versus space in film?

AW: Wow, good question. In retrospect, it may be similar because of the way you’re watching. In theatre, it’s like a box, and you just look. That’s why I think ‘Fever Room’ is a reaction to that switch. Actually, the view from the stage is really intimidating for me. Suddenly there’s empty seats, and I feel like shaking a little bit, and that’s what the theatre actors must feel to be watched. And maybe that’s a space for cinema, too. Usually you only see the image on the screen, so what about making the audience come inside this belly of cinema, belly of architecture, and turning the audience into the skin, into surface. This channel perspective is very important. It starts from the flat 2D cinema more, and then you realize that we never pay attention to the space, we just think about the screen in front, this image. But what about the space and the people around? I think ‘Fever Room’ tries to aim for that shift in perspective and be aware of this ritual that we have shared since we were in the cave. That’s why there’s a cave in the movie, it’s a reference to Plato. In the end, I think when the one screen comes down, that’s the whole point of the show, that suddenly this screen is different from the beginning screen, that you’re aware of the other people and you’re aware of the empty air before, the beam of light.

JR: The air has a materiality to it. So the ritual that you’re talking about—is this the ritual of cinema, of watching films, or is this a different ritual?

AW: It’s a ritual of dreams, which is linked to cinema and theatre, that we need to isolate ourselves for different experiences as a different way to digest realities. When we dream we have a wave in the brain, and it moves to different stages, like REM. And throughout the night when we dream, we move through these stages in cycles, and each cycle lasts 90 minutes. For me, that’s exactly the perfect length of cinema. I really believe that the duration of cinema is derived from this biological need to dream. That’s why when you’re watching a longer film, you go “Oh, that’s too long” because you cannot take more than 90 minutes. So I think of this in relationship to cinema and dreams, and that’s why we have virtual reality now. Because in dreams you can move, you have freedom. We always want to break free from this frame. In VR and the next technology, it will become more like dreams.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul: ‘Fever Room’, 2017. // Photo: Kick the Machine Films, Courtesy of Volksbühne

JR: Over the next 24 hours, is there one film in particular that you’re really excited to show in Berlin?

AW: In general, I love the movie ‘Syndromes and a Century’, because it’s such a no-plot movie. It’s such a marvel of architecture, of the memory of places where I grew up.

JR: Are you generally resistant to narrative?

AW: Kind of. Not resistant, but I think movies are not only stories, they’re vibrations of emotions. The books you read are an intellectual activity full of intellectual information. The movie is that, and also something invisible, the light. I was having a massage by a Reiki master that was supposed to feel universal energy channeling to your body. For me, it’s a little bullshit [laughs], because it’s more about the placebo effect. In order to have this effect you need to believe, and your body needs to react to the touch, and we don’t get enough touch. Touching is a very strong thing, and I believe that movies have the ability to touch, literally. I was talking to the sound guy today: with the sound it’s not only the waves, but also an aura, physically, but sometimes you forget that it hits you as this particle. And I think the movie wavelength vibrates between image and sound in the same way, but you need to believe. You need to be ready, or know yourself that you like a particular kind of wave vibration. That’s why you like movies but you cannot explain it. So it’s more than a story, it’s about many things.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul: ‘Fever Room’, 2017. // Photo: Kick the Machine Films, Courtesy of Volksbühne

JR: I was thinking about the cave in ‘Fever Room’, and what you were saying about the light being part of the film. I read somewhere that the cave paintings in Lascaux were the first form of cinema, because the light of the fire would flicker onto the paintings and animate them during rituals, which reminds me about the rituals you were talking about.

AW: Again, the need to create something beyond our vision, to create artificiality, illusion. We start from there until now, when we’re in ‘Fever Room’ it’s like a modern cave. It’s the same ritual that we keep continuing.

Additional Info

VOLKSBÜHNE

Apichatpong Weerasethakul: ‘Fever Room’

Screening/Play: Jan. 26 – Jan. 28, 2018

Linienstraße 227, 10178 Berlin, click here for map