Interview by Göksu Kunak // June 19, 2019

Safe. It is a big lie to utter the word safe, while Black folks are being murdered by official dark-blues, while the word rape still exists, while a big part of the Middle East is being displaced by some normative suits so that their weapons, their cars and their mainstream porn with racist remarks (“Arab cumshot”, “Turkish girl enjoying herself”, “Black cock fucks a redhead teen”) accompany them in dreams causing not only our but also their, suffering.

The things we were taught as etched in stone, are they really so?

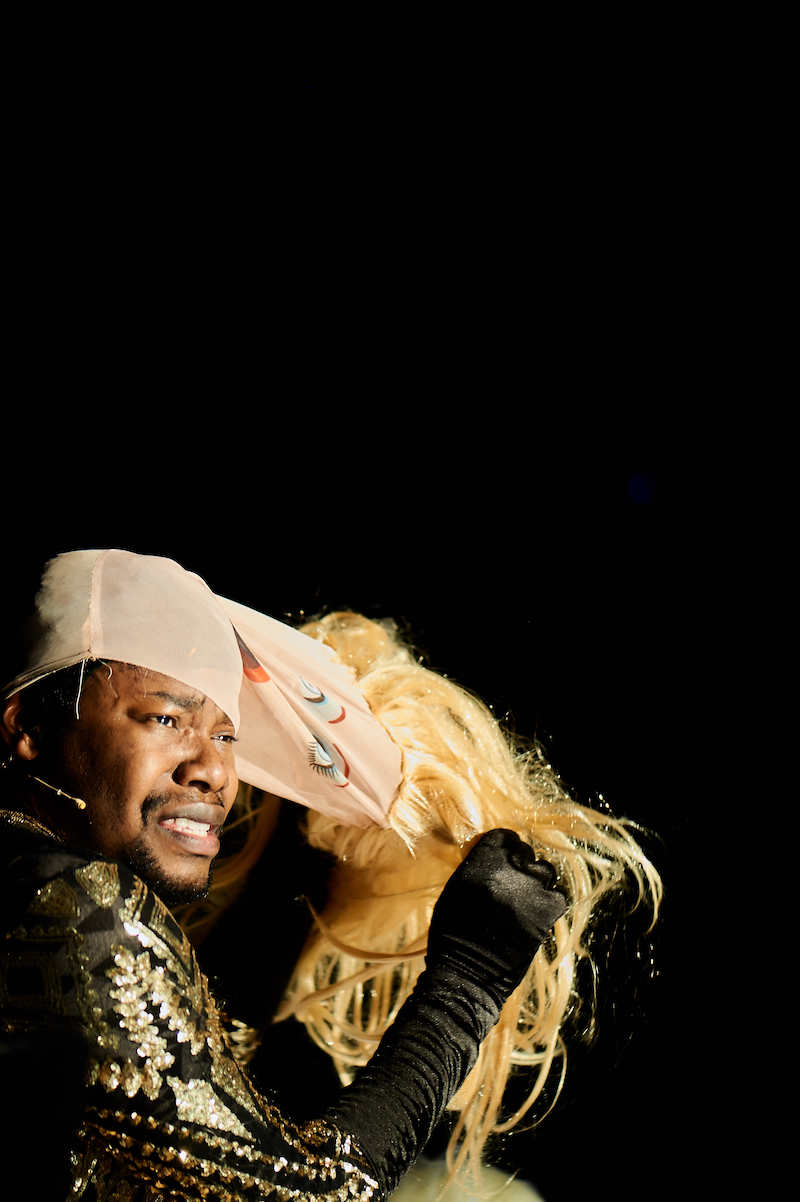

Pausing and feeling an indescribable intensity, after watching Jaamil Olawale Kosoko’s piece ‘Séancers’, was inevitable for me. A year after performing the piece at American Realness in New York in January 2018, Kosoko brought it to Sophiensaele in Berlin. In all his sincerity, he gave hints about the deaths in his family (loss of his mother at a young age, loss of his brother by murder) and talked about the deaths all around us. As it was a séance, various rituals were performed—tea time with a portrait of a lost one, diving into a pile of “things” and peeling them off one by one despite their (conceptual) heaviness. There was a skull, a blonde wig and the portrait of his mother—who passed away when he was 16—among other things, all wrapped in tulle. Some uncanny singing moments made me question if the artist purposefully played with the idea of the Black body as the “entertainer(!).” By the way, who made Micheal Jackson White?

Type a smiley at the end, otherwise, some will find it too much, too emotional.

Jaamil Olawale Kosoko: ‘Séancers’, 2018 at Zürich MOVES!, Zürich Switzerland, Tanzhaus Zürich // Photo by Len Olafson

Kosoko brings us to the effect and heavy burden of always being on the edge. In that sense, the piece itself registers access to the pace of the perpetually interrupted. What is seen as the artist’s own history is a collective trauma of a community, of a whole continent. More than just a representation, (t)his approach creates a form around tears and trauma, well, almost a how-to list. That’s why Black theory finds its way into his pieces. Theories around the Black imagination and Afrofuturisms/pessimisms tear down what is seen as holy.

“Never in a million years would I have thought that the world I’d be going into would be one that is performative, that is artistic and creative,” says Kosoko. Thanks to these performances, he repetitively sheds his skin off: skin that was sculpted with the help of patriarchal structures strengthening themselves via self-policing. And now, as a queer choreographer and poet, Kosoko—intentionally or not—points out that if one reaches out, there is wondrous power in the hidden traumas that would lead us to undo and relearn.

Kosoko’s contemplation provides us with tools to restructure the traumatic repetition—not to negate but to pierce through the ordinary and use these tools to heal and break apart. A place to play. Maybe that’s where Jaamil rests.

Jaamil Olawale Kosoko: ‘Séancers’, 2018 at Zürich MOVES!, Zürich Switzerland, Tanzhaus Zürich // Photo by Len Olafson

Göksu Kunak: You opened your performance ‘Séancers’ at Sophiensaele by saying “I’m playing with all the toys I was denied as a child.” How does ‘Séancers’ allow you to heal from past traumas?

Jaamil Olawale Kosoko: I feel things really deeply, almost too deeply. Even as a child, I felt a weird sense of guilt around my sensitivity. There are certain ways of posturing, being and performing one’s self that you’re not supposed to do, or have access to, as a young, Black child in America. “You don’t do this, you don’t do that”. Not only being Black but being a certain kind of boy. You’re told, “Be a man!” All these things we teach young boys; how they should be, how they can’t be. There is no room for softness or sensitivity or the possibility of other ways of performing one’s self unless you have very open-minded parents. Interestingly enough, I feel that only quite recently inside of my performance work, I’ve been able to really play with my own edges as they pertain to gender performance and sexualities and eroticism and pleasure. There are ways of being that are sensually blocked or that you are taught not to do. I find myself coming to terms and reckoning with a lot of childhood policing.

Jaamil Olawale Kosoko: ‘Séancers’, 2018 at Zürich MOVES!, Zürich Switzerland, Tanzhaus Zürich // Photo by Len Olafson

GK: Self-policing?

JOK: Yes, but also policing from my uncles, from my father, from my mother, even. Knowing what I know now, I understand that a lot of that information is learned behaviour. It’s a generational shift also: “How do I prepare this person for the world that I believe they will have to go into.” Never in a million years would I have thought that the world I’d be going into would be one that is performative, that is artistic and creative.

There is a kind of exorcism that’s also taking place inside ‘Séancers’. There is something about allowing myself to become fully, and then there is something about exorcising or expelling certain toxicities, behaviors; colonial behaviors, colonialist mentalities that have become embodied and embedded in my psyche, in my body, in my lived experience. I try to find a balance between these and essentially the performative platform becomes a place where that reckoning can occur. That’s why I’m so exhausted every time I perform this work because there is some real restructuring taking place. I feel my body is moving, is transforming, is healing. I do feel that! It may be through the emotional, through the physical or the transformations that occur metaphorically inside of the practice. All of it is working towards what I think is the embodiment of my own medicinal self-making or re-making.

Jaamil Olawale Kosoko: ‘Séancers’, 2018 at Zürich MOVES!, Zürich Switzerland, Tanzhaus Zürich // Photo by Len Olafson

GK: Among the various texts of the vigorous Black literature why did you choose to work specifically with Audre Lorde’s 1978 poem, ‘Power,’ Howardena Pindell’s 1980 short film, ‘Free, White and 21’ and a radio interview with the civil rights activist and theologian Ruby Sales?

JOK: It was something about these works that were coming up; it was almost as if they kind of self-curated themselves inside of the process. This is why it’s so important for me to share work in process and practice as a methodological perspective, just because it influences the way in which I’m building the work. As I was creating ‘Séancers,’ I was doing residencies and public showings here and there, literally testing the material, seeing how it landed, how the audience reacted to it. So, it was really in conversation with various groups of people and my personal lived experience. Specifically with Howerdena Pindell. She is from Philadelphia and the questions she was asking years ago seem to be naturally coming back up for me. Then, I found myself in Miami, at the Perez Museum and her work was on display. Sometimes certain works just keep coming at you, saying “you need to work with me”. While I was researching this project, this catchphrase ‘Free, White and 21’ became such a staple in American cinema for years after the Second World War into the Civil Rights era.

So for me, when I’m making a piece there is something auto-ethnographic taking shape, but there is also something about it that is asking for me to really delve into the historical proposal to understand what points in history I am trying to evoke, remind us about. In that way, I almost feel like an archaeologist. Like I’m taking the historical relics and brushing them off, even if they’re ugly or really problematic. It’s important that we continue to remember and bring these memories, histories back into the room no matter where they’re landing, they want to come back. It’s the same with Audre Lorde’s ‘Power’.

GK: Even now, Lorde’s poem is still so valid and explains so much in terms of what Black communities have been going through in the US.

She wrote that poem some forty years ago! It’s so powerful even till today. I just can’t shake that. That could have been written yesterday. It’s so incredibly important now. So, I believe that in the work of a number of intellectuals like Lorde or Baldwin, there are these maps, these road maps embedded in the work, in their texts that they’re leaving tools, medicine, prescriptions. And I do feel that I’m a part of that lineage of this extended family of writers, philosophers that are creating certain pathways for generations to come. I feel that weight deeply when I move in to make work, when I really delve into the criticality of particular proposals, I have to be aware of these histories. There is no other way.

Jaamil Olawale Kosoko: ‘Séancers’, 2018 at Zürich MOVES!, Zürich Switzerland, Tanzhaus Zürich // Photo by Len Olafson

Jaamil Olawale Kosoko: ‘Séancers’, 2018 at Zürich MOVES!, Zürich Switzerland, Tanzhaus Zürich // Photo by Len Olafson

GK: What is Black dramaturgy or Black writing for you? How to conclude in a fugitive way? How to crack the lineage of White performance making and White institutions? For instance, during the talk you were mentioning “Not being concerned with the final product that’s to come” and if, say, one of the performers is having a bad day that’s more important than the rehearsal or what is about to come for you.

JOK: I love this idea of Black dramaturgy. Practicing a kind of refusal inside of certain hegemonic realities, in ways of being. I’ve been thinking a lot about this, especially as I approach the final part of this trilogy of works consisting of ‘#negrophobia’, ‘Séancers’ and ‘Chameleon’. I think about the idea of refusal. There are learned ways of making of a piece of art, and I’m so grateful to have had certain training to get that data and to study the canons, but the more that I learn and lean into my own truth, and my own reality and my own needs, to be completely honest, and the needs of those around me—emotionally, politically, spiritually—I’m trying to find a way of making that feels more holistic. The stage is simply an extension of my reality, of my lived experience. It’s certainly a crafted space and time, a curated space, but I feel the way in which we’re positioning certain images, certain questions, certain intimacies is rising naturally out of the lived experience. What it means to create a community together to be in real dialogue, exchange and to crystallize those moments. This is how I’m learning and redirecting my practice now.

Jaamil Olawale Kosoko: ‘Séancers’, 2018 at Zürich MOVES!, Zürich Switzerland, Tanzhaus Zürich // Photo by Len Olafson

GK: Do you feel pressure as a Black artist to meet certain expectations to show ideas in a specific way, especially from the performance scene or within the White institutions?

JOK: That’s a good question and I have not concerned myself with it, honestly. It might have been a concern of mine, once upon a time, when I was emerging, looking for opportunities and trying to place my work but not anymore. The more that I’ve come to learn and understand my own interests and concerns, the realities of what’s happening in the world, it’s become more about how I frame myself, and how to share my research with the curators. I think, having stepped more deeply into my own power, I am aware of my critical position; I know the importance of what I’m doing in the world. Does the curator know that? Maybe not. It’s ok, so be it! I know, and I think the audience knows as well. My work has become less about fitting some expectation of a curator and more about letting that curator know how they need to be thinking about what I’m doing and the importance of it. Either they take it or not. I understand that it’s such an amazing benefit to have, especially as an American artist. There is so little resources, people are trying to get the few little dollars that there are. I’m very much aware of that position, to be nominated and to be invited is such a gift that I’ll never take for granted but I know my power inside of this work. I’ve studied curatorial practice, I’ve worked in that world. I know that job, so I feel very confident in my positionality right now and how I’m holding space for myself, for my team, for my community; for people of color in the world, for queer people. This also creates more dialogue. We really need to find each other at an even playing field, and not practicing these weird hierarchies.

Jaamil Olawale Kosoko: ‘Séancers’, 2018 at Zürich MOVES!, Zürich Switzerland, Tanzhaus Zürich // Photo by Len Olafson

This article is part of our monthly topic of ‘Unlearning.’ To read more from this topic, click here.

A longer version of this interview can be read here.

Artist Info

Jaamil Olawale Kosoko: ‘Séancers’, 2018 at Zürich MOVES!, Zürich Switzerland, Tanzhaus Zürich // Photo by Len Olafson