Interview by Noëlle BuAbbud // Nov. 3, 2020

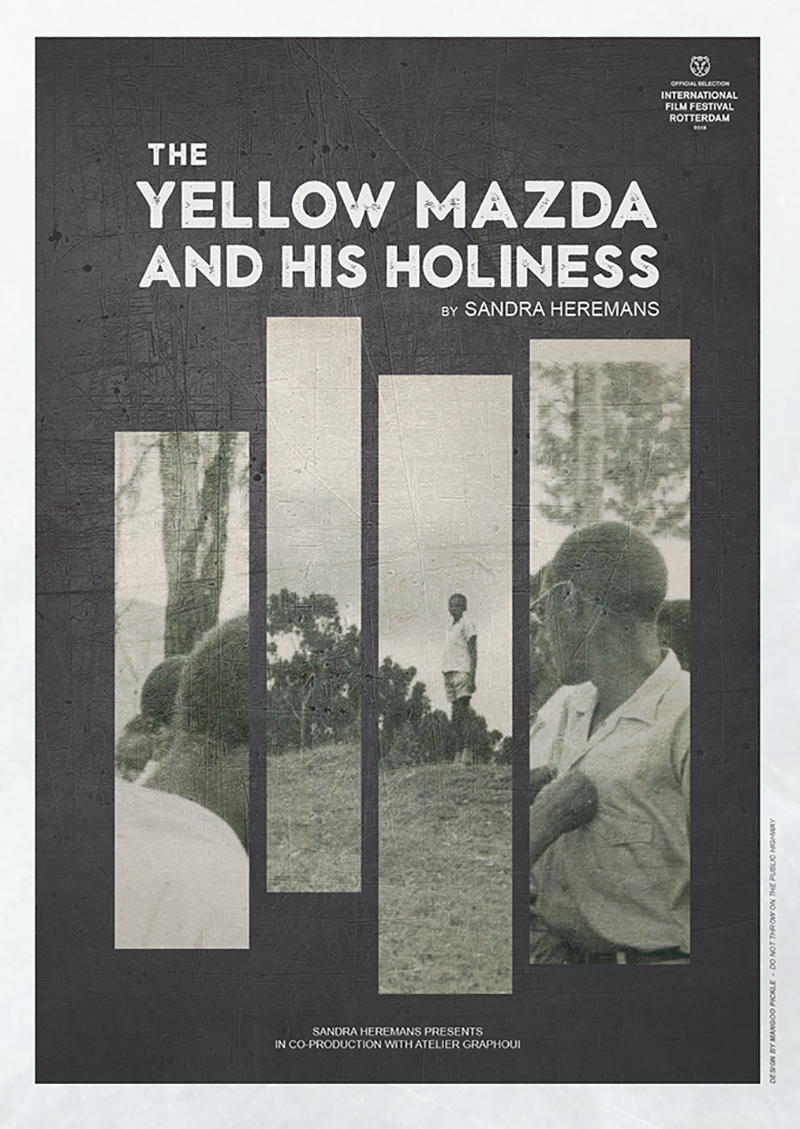

Collective memory and personal histories play an important role in decolonizing understanding and knowledge. The filmmaker, historian and cultural anthropologist Sandra Heremans addresses this idea in her film ‘The Yellow Mazda and His Holiness’. The filmic essay tells the story of her parents, a Belgian missionary who falls in love with a Rwandan woman, and the colonial history that Heremans is confronted with through imagery. ‘The Yellow Mazda and His Holiness’ has been selected as part of this year’s interfilm Festival Focus On: Postcolonialism. We discuss Heremans filmmaking as a point of departure for modes of decolonized consciousness and storytelling.

Still from ‘The Yellow Mazda and His Holiness’, 2018 // Courtesy of Sandra Heremans

Noëlle BuAbbud: In your work, how does your personal history act as a launching pad for wider critiques of colonial institutions, like the Catholic church and missionary service?

Sandra Heremans: The starting point is my family’s story. It’s not fiction nor a story of a third person. It is personal to a certain extent, but I tried to leave enough space for the audience to connect with it on different levels. The danger with personal stories is that the audience can disconnect, because it can be too singular.

I see this film as a kind of visual allegory, as a form of extended metaphor, in which persons and actions in a narrative are equated with the meanings that lie outside the narrative itself. In an allegory there are two meanings: a literal meaning and a symbolic meaning. The form of the film, on the other hand, is an objectification of the re- and de-construction of a narrative and about what to do with this heritage. This notion can be applied on a much broader level, I think, to society as a whole: Do we deal with our past? Which narratives are told? What is the missing narrative/missing image? What do we remember? And what do we do with this heritage?

The story is layered. The encounter between those two people touches on very clear symbols coming from the colonial era, such as missionary work, the catholic church, but also, a bit more subtly, the act of writing the history of the other, the act of projecting. It also touches on more intimate themes, topics such as loss, grief and heritage, things that a lot of us have experienced. Furthermore, on an individual level, it speaks about agency, the act of positioning oneself towards an institution and creating a family. And, through the form, I investigate the intimate and political potential of family archives and I experimented with the missing or imagined image through the black image.

NB: In ‘The Yellow Mazda and His Holiness’, you alternate between a black screen and archival images, and this formal choice is later mirrored in a written dialogue on screen that you have regarding a growing distance or gap between you and the world. How does this idea of the gap illustrate ideas of your authorship, image making, memory in a decolonial dialogue?

SH: The (family) archive has a great intimate and political potential. It is, on one hand, a reflection of an intimate moment, but can also be connected to bigger political and social dynamics. On the intimate level, it’s about the act of remembering. The alternation between the black screen and the archival image is formally investigating the notion of memory and recollection. It can also be read as a reference to the lost image and the imagined image. A memory can change in time as you are getting older. At some point, it can even become more of an imagined memory, based on what you are told. We fill a perceived gap with thoughts, images and ideas. It’s a metaphor for the act of creating.

On a more political level, there is the dialogue about the growing distance or the gap between the world and the self: the friction that is felt between the narrative told and the narrative felt. This can be connected to what is happening now, especially this year, during this ongoing pandemic. It feels like the West, which is defining himself by a severely idealized past, has begun the mourning of its own created fantasy. It feels like, under the pressure of this pandemic, it has entered into the negotiation phase of the mourning process. There is just something not right about the narrative that is told (about the past), there is a gap felt about the bodily experience of it. And now, what do you do with it?

‘The Yellow Mazda and His Holiness’ Poster, 2018 // courtesy of Sandra Heremans

NB: Can you tell us about your turn from academia to experimental film? How does this medium suit your research interests?

SH: I feel more freedom in understanding the image, in investigating reality, exploring human experiences through (moving) images and sounds. What attracted me in my Art History and later Social and Cultural Anthropology studies was the power, or more the affect, of an image. The (moving) image, with sound, can inherently touch an audience in the core of their soul. But during those studies I felt a conflicting relationship toward the use of words, concepts and ideas to “capture” and organize reality. It reduces the layered sensorial and chaotic human experience of the world to a cold, organized and static form: a form that doesn’t assume its subjectivity nor can it be questioned. Through the films of Maya Deren (film experiments) and Zora N. Hurston, I got introduced to a form that felt right. The subjectivity of the re-creation of reality is assumed and played with there.

I was also fascinated by Aby Warburg’s ‘Bilderatlas’. He collected images (from all possible places) on black panels, that he organized according to themes or geometrical forms. When looking at pictures of this ‘Bilderatlas’, it felt like those images were visually in dialogue, on a pre-symbolic level, and were restored in their spiritual charisma. This really inspired me in the editing of my film. The end of my film is connected to the beginning. The different photographs are in dialogue with each other, support but also question the narrative.

NB: How does your (formal) approach to filmmaking/storytelling challenge colonial ideologies embedded in the medium, specifically the use of documentary and archival footage?

SH: Every artistic creation goes through a human body. What inspired me in Art History is the fact that you can date a painting by its style. I say this because in the creation there is always a sense of unconscious collectivity present and also an unconscious individual style, there is a lot of unconscious stuff going on in our creating bodies.

In storytelling, this degree of subjectivity needs to be assumed. The objective act of storytelling doesn’t exist. The filmmaker is for me a sponge that fills herself with a story and ejects it in a film. It goes through a body, with its conscious and unconscious layers. In that objectivity, there is a dangerous power dynamic. Especially if the starting points are pre-conceived concepts. Also being aware that the colonial ideology (and fantasy) is still strongly embedded in daily interactions, as well as in the history of cinema.

I see editing as an instrument that can interact with the unconscious dynamics in the body. I attempted to use a cinematic language to show how I feel towards the narrative told, that I tried to de-construct, re-construct and to read between the lines of the images shown. I experimented visually with the notion of memory, remembering and also the act of the re-thinking of a narrative on the ‘black image’ or the non-existent image. I see a lot of potential in cinematographic languages, it’s still a relatively ‘young’ art form. A lot can be experimented with. It’s like experimenting with the evidence of the things not seen.

Exhibition Info

Interfilm Festival

36th Annual Short Film Festival Berlin 2020

Festival: Nov. 11–Dec. 13, 2020

interfilm.de

Streaming: sooner.de/festivals/interfilm

Still from ‘The Yellow Mazda and His Holiness’, 2018 // Courtesy of Sandra Heremans