Italian-born artist Quayola has developed a practice focussed around bringing back to life what are conventionally understood to be classical, and admittedly outdated images, particularly from the Italian Renaissance. Quayola’s works explore the composition of these images using programs and algorithms that allow him to abstract the image into shards of colors or select points of focus. He has also worked on creating sculptural models of his renderings of these images – something he aims to return to in the future, he tells me. In other works, Quayola has created animations in which these classical Italian paintings appear to crystallize and grow angular protrusions. His current show, Iconographies, at NOME Gallery focuses on a series of conscientiously printed works that resemble more closely the format of the still paintings that they are developed from.

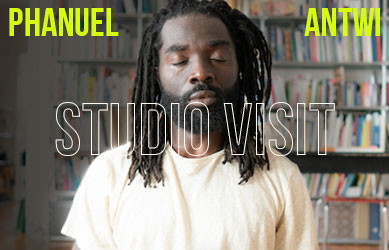

Iconographies #8102, Adoration, after Botticelli, 2015, ditone print // Image courtesy of NOME Gallery

We talked to Quayola about his paradoxical approach: one that both profanes and elevates the classical paintings. His works push the limits of the original image, both distorting it beyond recognition into incredibly precise geometric forms that could only be rendered by a computer, and at the same time revealing what was already there in the original paintings.

Alena Sokhan: What is your interest in these specific paintings?

Quayola: These images are deeply embedded in history and culture. These are all very iconographic works that are tremendously powerful. For instance, the theme of Judith and Holofernes is one of the most painted scene in the history of art. Many artists obsessively painted this image many, many times, sometimes only changing a few details, maybe as a pretext to explore this image further. I found this a very rich ground on which to base my own explorations. The Adoration of the Magi is another theme which has been explored extensively in classical art.

I am interested in the different ways of describing and looking at these paintings. I want to reach a level of abstraction that would allow you to see through the iconographic, traditional narrative, which is why my works are quite abstract and non-representational.

AS: Why distort them in this way? Why start with these images and not with something else, if they are barely recognizable in the end?

Q: I am interested in maintaining the tension that these works have with the original. For instance, ‘Iconographies #81-20’ shows this tension very clearly. One part of the work is a quote from Giorgio Vasari, who is considered the first art historian, in which he describes Botticelli’s ‘Adoration of the Magi’. Vasari’s version is very poetic and this quote in particular is interesting because in the end he talks about color, design and composition, these kind of qualities by which we could judge an image. What is interesting to me is how Vasari constructs a new language for looking at the painting, and evaluating it. The other part of the work is a a list of code, that also describes the same painting, though in a much different way. All the works in the exhibition are all generated with this unique framework of custom software that I use to look at these images in a way that I could not myself.

Iconographies #8101, Adoration, after Botticelli, 2015, ditone print // Image courtesy of NOME Gallery

AS: What relationship do you have to the original image?

Q: I want to re-understand these images and the values and ideas that shaped them. Also I have a personal motivation to do this: I grew up in Rome surrounded by these images, and was as a young person overwhelmed by the very intense culture and history that they carry. And I found myself wanting to run away from them, which I did when I moved to London at 19.

AS: What about them did you find overwhelming?

Q: Well I was running away from this dead past, which was very decadent, for sure, but at the same time it was this absolute symbol of perfection, that was gone and nothing could possibly compare to it. Also these images are connected to religion, to morals and traditions that are hard to relate to, especially as a young person. But after I moved to London, when I came back to visit I became very interested in these images, because I could look at them without being implicated so deeply in them and could now see them in a new way.

Iconographies #32, Judith & Holofernes, after Caravaggio, 2015, engraving on anodized aluminum // Image courtesy of NOME Gallery

AS: So do you think you could generate endless versions of the image? Does that devalue the originality of the original image, or the value of any one of your works?

Q: Firstly, I could generate an infinite number of images, and I think this is a good thing. The algorithm and the programs allow us to look at an image in a way that we did not have the possibility to before. The program is like an MRI machine – it scans the image in different ways.

I believe this process reveals an infinite number of possibilities for how we can look at something. I think each adds to the value: each image exposes a new method of perception and introduces a new image into the world. Each image is like the mineralization of one particular method of perception, each image the programs produced also represents infinite others that could be made. I like this metaphor of the mineral, and I want my works to be minerals, like the very old Byzantine Icons are very much minerals: they are cracked and fossilized from the way the paint has dried.

Iconographies #43, Judith & Holofernes, after Guercino, 2015, engraving on anodized aluminum // Image courtesy of NOME Gallery

AS: So as I understand it, you are using the algorithm to clear the ideology and tradition from our perception, to allow us to see the image without those influences. But would you say that technologies and algorithms are just part of another type of ideology?

Q: Certainly that is part of my ongoing exploration, and the issue you bring up is related to a much broader conversation about how technology is affecting our thinking. But I think it is important to note that all the works in here are not produced strictly with an algorithmic, analytical process, but rather a creative one. I have developed a system of programs and algorithms, and then I work extensively with the system to create an image that has value. I think I engage in a quite traditional form of image-making, that I believe is quite similar to how the original paintings were made. I focus on aspects like composition, design, color, focus, saturation, and so on.

I use additional tools to add additional enhancements and adjustments to the image. It is important to me that this should not be the documentation of a certain process, this should be a new object of contemplation, which is why the outcome of what I am doing is very important. I am very concerned with the physical presentation, the framing, the printing, and so on. I am not just printing a computer image.

A good analogy is that my system is like a synthesizer, the instrument that is used to make music. There is a system with many parameters, and you create new images by tweaking these parameters.

AS: What is your relationship to technology then?

Q: It is almost a collaborator, it is not simply a tool or a method. I like to be surprised by the system, to explore what is possible. I work with what the technology offers me, the types of images it reveals, rather than using it to render something I had already designed and preconceived. Through technology I can change my ideas and preconceived notions, my systems of vision can be changed by technology.

Iconographies #1601, Venus & Adonis, after Rubens, 2015, ditone print // Image courtesy of NOME Gallery

AS: How do you think your works relate to the original image?

Q: On one hand I use the original image as a point of departure. I try to look at it in a way we are not supposed to, and at the same time, the end result reveals something about those images, maybe the way that color is used, or how forms and compositions are constructed. At the same time, I am looking at the relationship between the formal aspects of the image, and I think that is very close to the original. Something is driving the power of these images, there is something dynamic and alive in these images, and I am trying to find it.

Exhibition

NOME

Quayola: Iconographies

Exhibition: Jan. 15 – Mar. 05, 2016

Dolziger Straße 31, 10247 Berlin, click here for map

Writer Info

Alena Sokhan is working on her Masters in Media and Communications at the European Graduate School. Her research interests lie in the topics of Queer Theory, Critical Theory, Film and New Media Art, and Economics.