Article by TL Andrews in Berlin // Thursday, Sep. 29, 2016

Photographs only really became a staple in journalism from around the 1920s. Before then illustration, or so-called pictorial journalism, was the norm. Audiences experienced everything—from gruesome scenes in the American Civil War to grand openings of the latest architectural marvels—through an artist’s hand. Ironically, that era is so long-forgotten today that when Molly Crabapple illustrates glimpses of injustices around the contemporary world, it feels novel again.

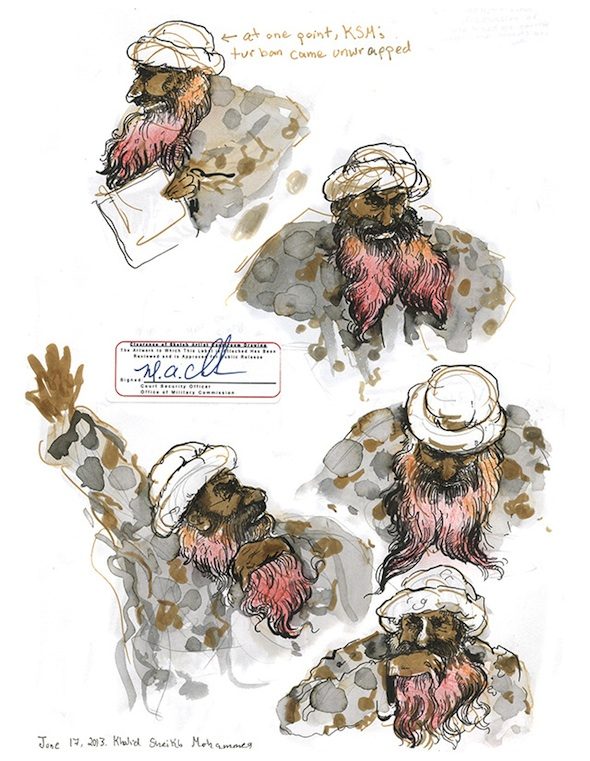

Molly Crabapple: ‘Drawings of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed from Guantanamo Bay’ // Courtesy of the artist

But beyond the retro flair some might attach to her work, Crabapple’s rediscovery of this ancient art form is notable because it gives her a unique ability to tell under-told stories. Reporting for VICE magazine in Guantanamo Bay, for example, she could side-step a partial ban on photography by publishing illustrations instead, thereby providing insights that a more literal medium might not have. She is a writer, too. And it is when she allows both skills to come together that her real potential is unveiled. Whether she is reporting on her arrest during the Occupy Wall Street protests, criticizing Donald Trump’s construction projects in Dubai or recounting the plight of migrant workers in Abu Dhabi, the seemingly anachronistic combination of her writing and illustration allows her voice to be heard an octave above the tech noise we’re used to. This September, she completed a project with Jay Z, in which she illustrated the history of mass incarceration in America. Crabapple spoke to Berlin Art Link for our month on “work” to reveal what goes into her creations.

TL Andrews: What are some of the challenges involved in writing and illustrating the same story?

Molly Crabapple: Drawing is easy for me. I’ve drawn since I was four years old, and at this point it’s somewhere between obsessive compulsion and my best means of communication with the world. Writing is hard. It was hard when I wrote my memoir, ‘Drawing Blood’, and it was hard when I reported from Pennsylvania prisons and from Gaza. Because reality is almost infinitely complicated, and stories have word limits; there are always going to be some sins of omission, and I suppose it’s the possibility of those sins that haunts me.

TLA: A lot of your work looks at power disparities that arise from economic inequality. Why would you say you have chosen to tackle these issues?

MC: My father is a Marxist, and I live in New York, one of the most staggeringly unequal cities in the US, that has become more unequal since I was born here 33 years ago, by orders of magnitude. It’s the city of glittering skyscrapers owned by Russian oligarchs, and undocumented women getting cancer at nail salons, painting the nails of those oligarchs’ wives. It’s a Maximal City, with all the classes smashed together.

TLA: Many of your stories are in essay format, with you playing a central role. What are the difficulties involved in inserting yourself into the story and the celebrity that may accompany that?

MC: In most of my reporting, I don’t play a central role. Though I’ll certainly make note of my presence where necessary, like to speak about how censors looked through my sketchbook at Guantanamo Bay, or how I had to sneak onto a construction site in Abu Dhabi in order to speak with workers in an uncensored fashion. However, neither I nor anyone else is an invisible transparent blob objectively documenting the Earth. None of us has god-like omniscience. Who we are affects how people treat us, what answers we get, the places we have more or less difficulty accessing, and if you write yourself out, that can conceal this fact.

TLA: What have you learned about power and economics through doing your kind of work?

MC: Artists are often Fabergé egg makers pretending to be revolutionaries, and journalists are just as often vampires, packaging the worst days of others lives and selling them to a First World audience. But despite all of this, I believe in both fields.

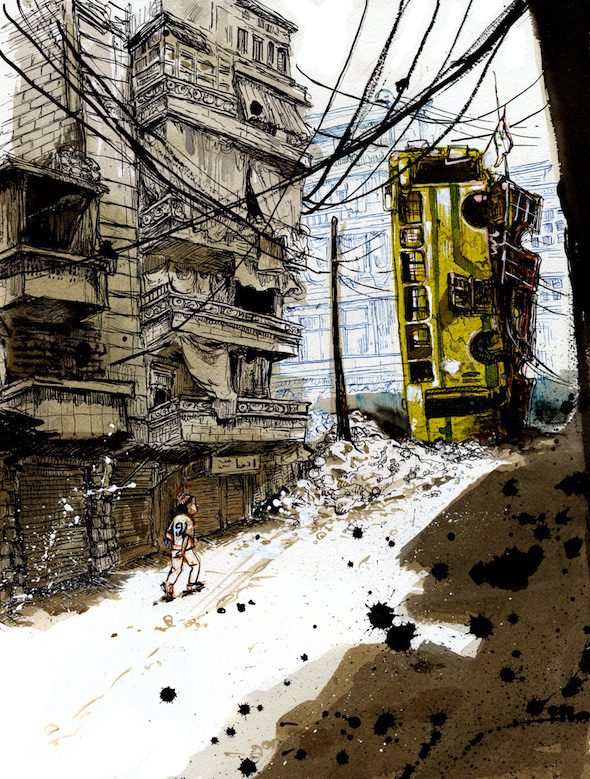

Molly Crabapple: ‘Bus Placed Between Buildings to Block Snipers’. Aleppo, Syria // Courtesy of the artist

TLA: What do you see as the storytelling power of illustration (as opposed to photography or video, etc.)?

MC: Art is done by hand, and since we live in an age of utter image glut (I think more photos were taken in the last decade than were in the previous century), the sheer humanity and novelty of a hand-done image has a different sort of power.

TLA: What specific challenges of representation are inherent to illustration? In other words, do you spend a lot of time thinking about stereotypes and how to represent your subjects in a way that does not perpetuate problematic beliefs?

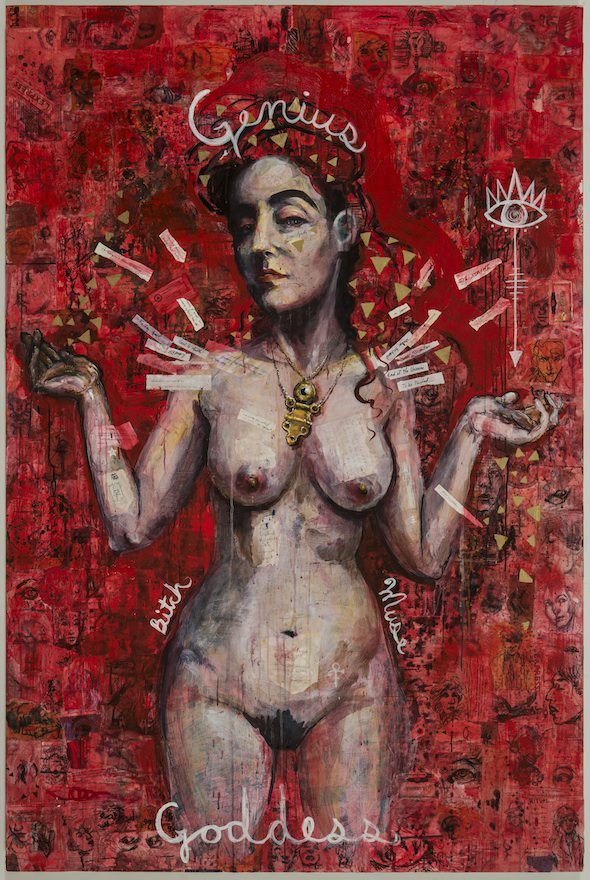

Molly Crabapple: ‘Annotated Muses: Kim Boekbinder’ // Courtesy of the artist

MC: I speak to friends in the communities I portray about stereotypes, cliches and idiocies that are frequently employed when portraying people like them, then I avoid those. I also ask them what they want to see.

TLA: Who are some of your biggest influences in the world of illustration?

MC: There’s little difference between fine art and illustration, so I’ll just pretend you said art. Goya, Dix, Ralph Steadman, Toulouse Lautrec, my friend Ganzeer, Diego Rivera, my partner Fred Harper, and my mom, an amazing artist in her own right.