by William Kherbek // July 20, 2021

It has been more than 50 years since Roland Barthes published the profoundly influential essay, ‘The Death of the Author.’ In the piece, Barthes created a philosophical architecture for a set of concerns that had long troubled authors (living and dead): what is the nature of authorship? What strictures does it impose? Where, if anywhere, does its legitimacy lie? Barthes wrote that “to give a text an author is to impose a limit on the text.” Perhaps this is true, but writers from the Dada movement through Barthes’ own time were devising their own methods for challenging the limits of authorship. The Dadaists had pioneered the cut-up technique, combining found texts to create poems. T.S. Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’ featured appropriation as a modernist tool. Hope Mirrlees’ ‘Paris’ explored the ways in which text and type interact to create narrative. The limits of authorship have found a new frontier in the age of machine learning. The publication of ‘Pharmako-AI,’ a novelistic collaboration between the writer K Allado-McDowell and the GPT-3 text generation system, was the first major attempt to bring AI into the field of literary production. One can imagine Barthes savouring the expansive possibilities for dispersed authorship AI licenses.

The English poet and publisher Sam Riviere is known for works that challenge ideas of originality and authorship. Riviere harvests language from various sources to create some of his poems. His 2015 collection, ‘Kim Kardashian’s Marriage,’ for example, was entirely created from second-hand language. Since the publication this year of his first novel, Riviere has begun experimenting with integrating a GPT system into his own writing practice. Co-authorship with an AI, in Riviere’s recounting of his experience, sounds less like the confrontation of a limit, than a starting point. Perhaps it signals another change in the reader-writer relationship, if not the “rebirth of the author,” then a kind of digital afterlife of the author.

Portrait of Sam Riviere // Photo by Jonathan Pryce

William Kherbek: Your most recent work is a novel, ‘Dead Souls.’ As a poet, were there differences you noticed in the process of writing, particularly in the way you approached depicting or representing subjectivity?

Sam Riviere: I didn’t really grasp this until I started writing the novel, but I started to think of subjectivity as a kind of flow, as a continuum, and the poetry side of my brain would be like: “yes, but you have these little sharp moments that stand out, these little realisations. Isn’t that how memory works?” Little sharp explosions that you map somehow. It’s something to do with representing cognition.

I started out writing fiction and then moved away from it. I had all sorts of problems with a totally immersive fictional world, because part of me would feel that it was too much artifice. You’re creating a sort of tunnel—and writing does feel a bit like digging a tunnel—you’re going back to it every day, extending its length. In a sort of fairly conventional novel, that’s the reader’s experience, they’re in this immersed tunnel frame of mind and carried along by it. Maybe this ties to having an art school background as well, part of me would resist the idea of that. As soon as something becomes too coherent and stable, isn’t that where it should be intruded upon, and reflected upon?

I want to have this sense of flow, or like being in a tunnel, but I also want the reader to be occasionally dipping out of that and seeing the architecture of it, realising that what they’re in is made up, and, more than that, it’s a disguised version of reality; kind of an augmented thing that slides down on top of the real world, and you’re looking at it, but you can still see the real world past it.

I suppose with poetry the appeal is that it’s like a little circuit breaker or something. You plug a reader into it, and it that fries their circuitry for a minute. It’s easy to point out the fallacy of a narrative way of looking at life. You could never construct the story of your life in any convincing linear way, because the sheer quantity of stuff you’d have to leave out would mean it would be this fishbone version of your life that probably doesn’t feel very real. In English fiction, the conventions of realism are not “real” at all. They’re just conventions that we’re in the habit of reading as real, a bit like a soap opera. We think they’re quite real, but if you actually examine the codes of that kind of representation, the adherence to reality is quite tenuous. It’s just a habit that we think about it in that way. With poetry, there’s always a part of me that would think of it as something more authentic, about that interruption of linear representation. I have a two-brained feeling about it.

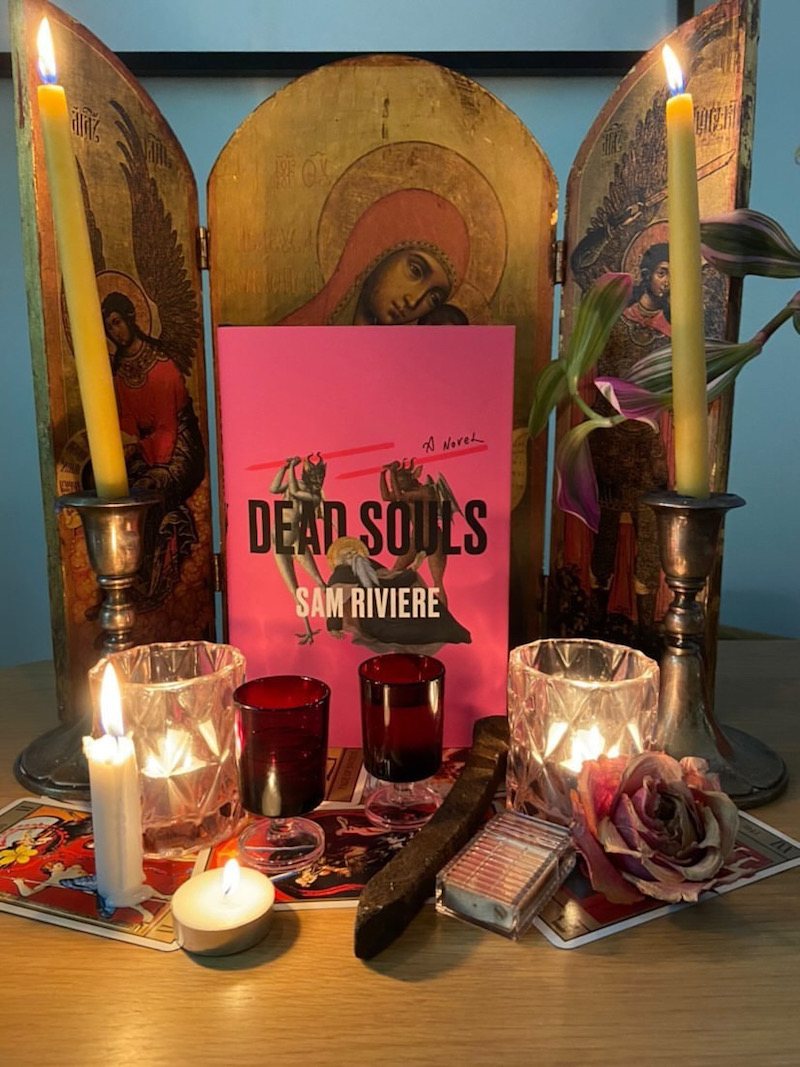

Sam Riviere: ‘Dead Souls,’ book cover // Courtesy of the author

WK: The idea of subjectivity is also central to your current project, which I believe you’re working on with an AI? How is that disrupting, or confirming your intuitions about, or ways of working with, poetry?

SR: A poet friend, Charlotte Geater, had written a pamphlet I published about a year ago where she used GPT 2, I think, which is what I ended up using, too. First, just as an experiment, because it’s free software. There are various interfaces, and I found a particularly accessible one where essentially I would just start with a title; then, you’re given a set of drop-down options every word or two. I inputted one of my previous books, ‘Kim Kardashian’s Marriage,’ which is, itself, completely made from found text. It’s an interesting question about individual style, I suppose, and if that’s connected to individual subjectivity. Through writing the Kardashian book, which is kind of like an old-fashioned bricolage text—it’s all sourced online and collaged together—I was able to hear my own voice in those poems, despite their being generated outside me completely. And readers felt that it sounded quite similar to my first book. It was kind of me, and it kind of wasn’t. With this new project, I was intervening more because I wasn’t taking whole sentences. What came out seemed to be this slightly scrambled or slightly misheard version of my own voice. I could certainly hear myself in it.

The strange thing is that language is exactly that, anyway: we’re all using a language that we didn’t invent. We occupy that language, and tailor it to our own requirements. I’ve definitely noticed myself stealing a certain phrase from a friend or something, if I found it particularly satisfying. A friend uses the word “confected” quite a lot and I started finding myself reaching for that word, which I probably never used before. A friend told me he’s writing poems in this method, too, and he sent me quote that the musician Holly Herndon said: that it’s not really about the computer being better than you at composing things, of you being the human version and the computer being this kind of Terminator poet. It’s more that you can make use of this interface or software to become more individualised, or more human.

I guess it’s leaning towards feeling a slight bit 90s cyborg. Actually, the technology is invented by humans, and it’s linguistic, so the wrong way to see it is that it’s going to supplant. It’s more that it’s going to augment in a certain way. That is the potential, or the utopian idea. My fear would be that it would just end up that a lot of the poetry created in this way would sound the same, a bit like flarf. At first flarf was hilarious, but because it’s hellbent on seeming like non sequiturs, and comedy, and irreverence and how many poems do you read before you think: “yeah, I get the idea now.” It’s almost as if it’s a style of poetry that inhabited a group of people at a certain point. Maybe that’s not different from a normal literary phase or style.

Sam Riviere: ‘Kim Kardashian’s Marriage,’ book cover // Courtesy of the author

WK: It may seem a bit incongruous or “futuristic” working with algorithm-driven processes to create poetry, but you could think of poetry as having algorithms embedded in it from the earliest days, e.g. epic lists in epic poems, or sonnet forms.

SR: Yeah I think it actually makes me think that the earliest poetry was certainly an oral tradition. The goals of an oral tradition are not originality, or powerful individual reflection; it’s about a good story. It’s also a story you should be able to memorise if you hear it. So it’s a kind of text that doesn’t really sit with an original author, but it spreads. A story is kind of a viral thing anyway, a folk story inhabits different people.

Maybe this is a bit too utopian, but could we circle back to the idea that a good poem or even a good process of writing poetry is one that surpasses the individual author, that isn’t really about the individual author’s virtuosity? Really, individual authors are like a field that the poetry inhabits, and that might be a quite large group of people. I think you get glimpses of that, like with the Surrealists. There’s a sense that they’re all tapping into the same kind of energy, or the same way of thinking about process, and, sometimes, the works could slide across and be by one or two people. It didn’t seem to matter much. That being said, I still feel a strong affiliation with the notion that the only way we understand poetry is from its individual basis. Someone’s poetry only really makes sense when you stack it up under their name. Maybe we’re going to move away from that eventually, and maybe that would be good, or maybe that would be really dystopian. It seems to me a lot of the literary projects of the 18th century, or the 20th century as well, for obvious reasons, were to do with the human point of perception as indivisible and unique, and you can’t dispense with that. It would seem like we haven’t got past the point of needing that reminder.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Poetics.’ To read more from this topic, click here.