by Nina Prader // Sept. 14, 2021

‘Redemption Now’ is the title of the Israeli, Berlin-based artist Yael Bartana’s retrospective and newest commissioned work at the Jewish Museum Berlin, curated by Dr. Shelley Harten and Dr. Gregor H. Lersch. The exhibition brings together more than 50 early and more recent works, including a swooping three-channel installation that cinematically explores the fantasy of the messiah, a series of photographs and neon works. The aforementioned impressive video installation reflects on Germany’s post World War II collective memory. Distinct reoccurring visual methods abound throughout this display of Bartana’s oeuvre, with speculative strategies that envision and question the many forms that repair and redemption can take in society.

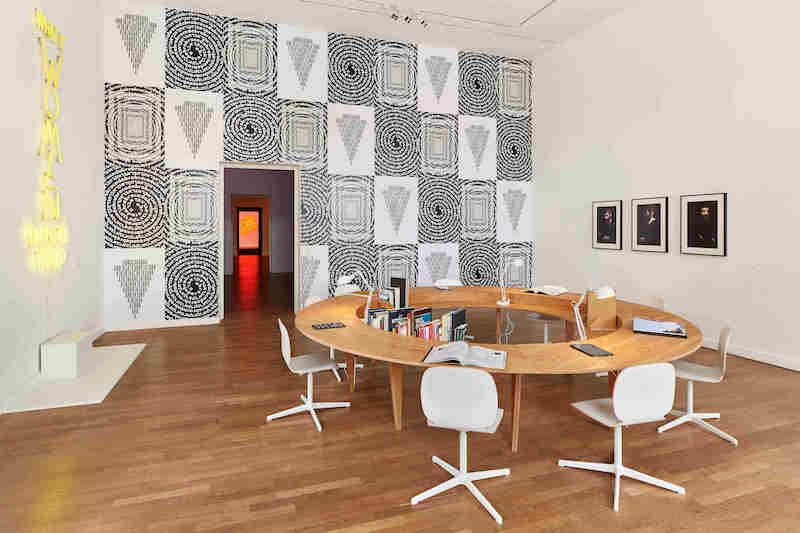

‘Yael Bartana – Redemption Now,’ 2021, exhibition view, Jewish Museum Berlin // Photo by Yves Sucksdorff

Each work sets up a different set of catalysts, places, signs, collectives, codes and motivations for repairing a broken society. However, the act of resistance is a crucial element in all her works. For Bartana, art is a tool that aids the anti-fascist struggle, making representation possible and recharging cultural narratives. The first work to set the tone in the retrospective is ‘Entartete Kunst Lebt (Degenerate Art Lives)’ from 2010. A super-8 projector animates a series of avant-garde paintings, such as ‘War Cripples’ (1920) by Otto Dix, depicting World War I veterans. Avant-garde art movements—such as Expressionism and New Objectivity—and their adherents were persecuted during National Socialism. Music, literature, performing and fine arts were deemed “degenerate art” by the Nazis. Yael Bartana empowers these wounded characters by animating them. They creak forward, zombie-like. Many of them have lost limbs, wear eyepatches, rest on crutches, scoot in wheelchairs. The display seems inspired by the notion of a “crip” revolution—a term coined in the 1960s, as a self-description of people with disabilities who demonstrated for equal rights. A movement is reborn and gains traction.

Yael Bartana: ‘Entartete Kunst Lebt (“Degenerate Art Lives”, excerpt),’ 2010, animation, 16 mm film and sound, 5 min // © Courtesy of the Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam and Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv

So much damage in society is caused by gendered, homophobic, racial, antisemitic and nationalist violence. The retrospective meanders through identities and where they collide, commune or divide. Jewish identities (plural) take shape on a spectrum. They are explored, redefined and debunked, from conservative to secular. Identity can be both polarizing and intersectional, alienating, educational and a tool to build common ground. Yael Bartana’s camera acts as an objective anthropological lens, following, for example, the Orthodox Jewish community during the holiday Purim in Jerusalem (‘When Adar Enters,’ 2003 and ‘Ad de’lo Yoda,’ 2003); watching highway traffic in Tel Aviv during the moment of silence to commemorate fallen soldiers (‘Trembling Time,’ 2001); or a group of Israeli teenagers wrestling in a role-playing game, reenacting the evacuation of the Gilad settlement (‘Wild Seeds,’ 2005). In every encounter, her camera captures the potential for conflict and reflection, if not resolution. The past, the present and the future exist in a time zone beyond reality. These films form part of a methodology Bartana refers to as “historical pre-enactment,” which commingles fact and fiction.

Palpable alternative universes emerge, but are they any better? The films set on loop, endlessly perform these struggles and longings, searching for redemption over and over again. They speak to German, local struggles but also pan-European and global wounds. Perhaps her best-known work is the ‘Jewish Renaissance Movement.’ The fictive film series, manifesto and conference entitled ‘And Europe Will Be Stunned’ (2009–12) explores the question: what if 3.3 million Jewish people were repatriated to Poland? Different people of all genders from the diaspora convene: the Jewish-Left, Palestinian, Israeli, Polish, German, American. The renaissance’s regalia (or merch) in red, white, and black conflates symbolism, with a star of David, a Polish eagle, EU stars, and the United Nation’s olive branches. The manifesto is multilingual. The discussions add salt to wounds, brainstorm options, share bitter irony. An alternative solution for reparations opens up another can of worms.

‘Yael Bartana – Redemption Now,’ 2021, exhibition view, Jewish Museum Berlin // Photo by Yves Sucksdorff

By readjusting the social choreography, Bartana shifts cultural storytelling. A recurring method she uses is queering gender norms. Challenging assumptions, Bartana herself makes a cheeky cameo in drag as Theodor Herzl (Herzl I–III, 2015), the Austro-Hungarian journalist known as the founder of Zionism—the philosophy of Jewish self-determination, applied differently by socialists and nationalists. Most often, women lead the social movements in her films. At the museum, a reading room installation and a yellow neon sign, reading ‘What If Women Ruled The World’ (2016) sets up another conference scenario. The sign is named after a performance of the same name about disarming nuclear weapons. ‘The Undertaker’ (2019), a film set in the birthplace of democracy, Philadelphia, follows an armed group—led by a white-haired woman—to bury their weapons, inspired by an indigenous ceremony. Would the world be less of a militarized place if women ran the show? Malka Germania (The Queen of Germany)—the newest messianic character in Bartana’s repertoire—appears in the exhibition as another case in point.

All in white, Malka Germania pensively watches a dystopian dream sequence of events unfold. Her exact role and function are never named, however, her presence is commanding and monumental. Strange things start to happen. Nazi architecture by Albert Speer emerges from Wannsee, Jewish Orthodox men change German street names into Hebrew, German symbols of national German identity, like golden soccer balls or flags, are thrown out of windows. The past crops up once again on German soil. According to author Max Czollek, the success of winning the soccer world cup in 2006 symbolized a sense of problematic relief for the mainstream majority, enabling German society to re-embrace their nationalist identity in the post World War II era, kickstarting the timeline of what we see today in the news. Bartana’s golden soccer balls seem a literal reminder of this analysis. Soldiers stand as a warning, guarding the Brandenburger Tor. Loaded signifiers when relocated to Palestine and Israel. Bureaucratic-looking individuals are seen heading for the train tracks on a long march with their jet-setter carry-on luggage. Norm-core youth with buzzcuts jog in groups through the woods and avant-garde dancers contort into power-poses. A Jewish takeover and a fascist return seem to exist in the same time zone. A new era is in the process of setting in, the phase before passing judgment. The work speaks to the burden of taking on the shame of collective memory: the desire to let go of the blame, enter a healed normality, a mythic band-aid in German commemoration culture known as the so-called Wiedergutmachung. However, the inter-generational trauma in Germany is ever-present and non-linear. Time does not necessarily heal all wounds.

Yael Bartana: ‘The Undertaker’ (film still), 2019, one-channel video and audio installation, 13 min // © Courtesy of the Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel Aviv, and Petzel Gallery, New York

Yael Bartana’s work illustrates the notion of redemption as both a fantasy and a process. This reparative process requires an active shift. It is accompanied by rituals, the creation of new pathways, diagrams, maps and social constellations. A new formation must take shape: a performative symbol hoisted or destroyed, a building built collectively. Bury your weapons, throw out what no longer serves. In Judaism, tashlikh is a ritual as part of the Jewish new year, where sins are symbolically thrown into a body of water as a rite of atonement. Bartana’s retrospective is an encounter with the many faces of redemption, depending on who is looking for it. Every era produces a different messianic possibility. Perhaps redemption lies in embracing the idea that collective power struggles and desire for change are never-ending.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Repair.’ To read more from this topic, click here.

Exhibition Info

Jewish Museum Berlin

Yael Bartana: ‘Redemption Now’

Exhibition: June 4–Nov. 21, 2021

jmberlin.de

Lindenstraße 9–14, 10969 Berlin, click here for map