by Dagmara Genda // Nov. 9, 2022

Supposedly video game players make good soldiers, or at least the French and American armies think so. Both recruit fighters through video games, explains artist and filmmaker Antoine Chapon, whose 2020 short film ‘My Own Landscapes’ can be seen in the documentary section of the Interfilm Short Film Festival in Berlin. The film features a monologue based on the story of a video-game-designer-turned-soldier, who returns from the war traumatised. Using a mixture of real and found footage, as well as scenes from a game editor, Chapon traces a former soldier’s methods of coping through the very thing that caused him to join the army in the first place—video games. Instead of designing simulations of conflict, however, the veteran now spends hours designing landscapes through which he can roam, swim and observe the tiniest movements of branches and leaves. In our interview, Chapon explains how video game engines can reveal stories of trauma and produce images of things we otherwise would never be able to see.

Antoine Chapon: ‘My Own Landscapes,’ 2020, video still // Courtesy of the Artist

Dagmara Genda: How much of ‘My Own Landscapes’ (2020) is a true story and how much is invention?

Antoine Chapon: The film is a combination of the soldier’s story and research I did on the recruitment of video game players in competitions organized by the US Army. They believe that good video game players can make very good killer drone pilots. Sometimes two soldiers drive through poor neighborhoods in the US in a red hummer with a big screen and a Playstation in the trunk. They stop and make young people play a video game produced by the US Army. They also recruit with online video games. An American general once said in an interview that it is far cheaper to recruit that way.

DG: What brought you to be interested in this topic in the first place? Harun Farocki seems to be a strong influence in this work.

AC: It was when I began a series of interviews with former French Army snipers that I discovered that the French Army had a new video game ‘Spartacus’ to train its soldiers. All the veterans I interviewed had PTSD, including one who shot and killed a child in Afghanistan. While continuing my research on the different types of simulation in the French and American armies I discovered the work of Harun Farocki. During my research for ‘My Own Landscapes’ I felt close to ‘Serious Games’ (2009-10) and ‘Parallel’ series. Today, I feel closer to ‘Images of the World and the Inscription of War’ (1988).

We can also talk about the important work of Forensic Architecture— ‘Torture in Saydayna Prison’ (2018), for example, where they model in 3D the Syrian prison of which there is no image of the interior. From the sound memories of former prisoners they reconstructed the spaces as precisely as possible.

Antoine Chapon: ‘My Own Landscapes,’ 2020, video still // Courtesy of the Artist

DG: Why did you choose to have a female voice narrate the story?

AC: I chose a woman’s instead of a man’s voice for three reasons. First, the veteran in front of the camera didn’t want to talk. So I asked myself how I could tell this intimate story but make it clear that it was not his voice. Secondly, this gap between the testimony and the images seemed coherent to me because the film is about the evolution of different identities. Everything changes in the film: the avatars, the landscapes, the soldier. It also gave me more creative freedom. Finally, I wanted to avoid this kind of virile male voice that one often finds in films and documentaries about war and PTSD.

DG: Are you interested in virtual reality and video game technology as an expansion of film? Where do you think the drawbacks and possibilities lie?

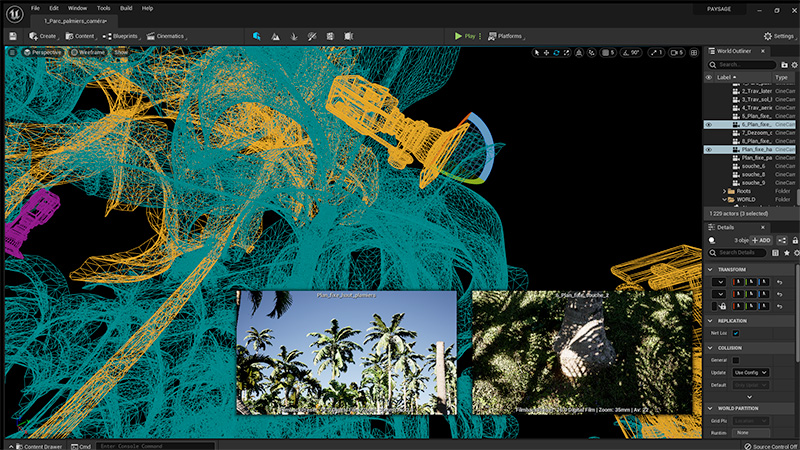

AC: I got interested in it for ‘My Own Landscapes’ by using the editor mode of the video game ‘ArmA III,’ the same editor mode used by the French and American armies. I was fascinated by the possibilities and the facility of creating worlds in this video game. For my next film ‘بساتين’ (The Orchards) I continue to be interested in these links. I will be using the Unreal Engine 5 software that is also used by the film and video game industries. The latest video games ‘Tekken’ and ‘The Matrix Awakens’ were made in this software. The question is how to appropriate these virtual tools and how to hijack them.

My interest in virtual reality and video game technology is to make missing images. Jacques Rancière says in a monograph dedicated to Alfredo Jaar that the debate about too many images in the era of the Internet is the wrong debate. It is better to ask: who is making and disseminating these images? To whom are they addressed? There are not too many images; there are many missing images, such from the Saydnaya prison or the war in Yemen. Trevor Paglen still says that there are too many images in line with the thesis of Jean Baudrillard, but we must be more precise in our analysis of images, as Rancière and Forensic Architecture are.

Antoine Chapon: ‘My Own Landscapes,’ 2020, video still // Courtesy of the Artist

DG: Can you let us in on some upcoming projects?

AC: ‘بساتين’ (The Orchards) is a film about a neighborhood in Damascus: Basateen al-Razi (the orchards of al-Razi) razed by the Assad regime in 2017. The neighborhood was inhabited by workers and farmers who rose up against the regime in 2011. This neighborhood was also known for its large orchards in the heart of Damascus. The fruit trees were very old. When Assad’s army chased the demonstrators into the street, some of them hid themselves between the trees.

Antoine Chapon: ‘بساتين’ (The Orchards), video still from in-process video // Courtesy of the Artist

The Assad regime is now building a luxury district to replace this demolished neighborhood. Thanks to Unreal Engine and VFX tools, I model the new neighbourhood including the parks of palm trees that are being built for future tourists. My film will appropriate and subvert the animations published by the Assad regime by combining them with the testimonies of witnesses, images filmed with smartphones. I am also integrating a simulation of a virtual crowd—a demonstration in the streets. Archival images from past demonstrations will be integrated into the avatars in Unreal Engine. Thanks to motion capture, several dances that were seen during the Syrian revolution will be integrated into the 3D animations.

I’m interested in the relationship between the revolution, the memory of a destroyed place, a construction project and the new 3D animations published by the regime to lure investors to the new luxury district. The regime wants to attract tourists and spread the propaganda under the slogan: “Syria Always Beautiful.” There are vloggers making stories on Instagram claiming that “everything is fine in Damascus and everyone can come there because there is no more war.”

Ultimately the idea of the film is to hijack the images of power, to rewrite the story of this razed neighborhood against the official story of the regime. In the heart of the planned glass buildings where future tourists will go in 15 years, the dance of the witnesses will be seen again on the land of Basateen al-Razi.

Antoine Chapon: ‘بساتين’ (The Orchards), video still from in-process video // Courtesy of the Artist

Festival Info

Interfilm

38th International Short Film Festival Berlin

Nov. 15–20, 2022

interfilm.de