by Adela Lovric, studio photos by Ryan Molnar // Feb. 11, 2023

Noises from the nearby construction site disturb an otherwise idyllic morning at Ana Alenso’s studio in Berlin-Wedding. It seems, however, as if the droning soundscape of heavy machinery extends from the artist’s workspace. Boxes and heaps of miscellaneous objects line its walls—from assorted metal scraps, tools and scaffolding tubes to electric motors, vehicle parts, oil barrels and a few other props that are instantly recognizable from Alenso’s artworks. They were all once discarded at places like recycling centers, landfills, basements and streets before the artist collected them for her projects.

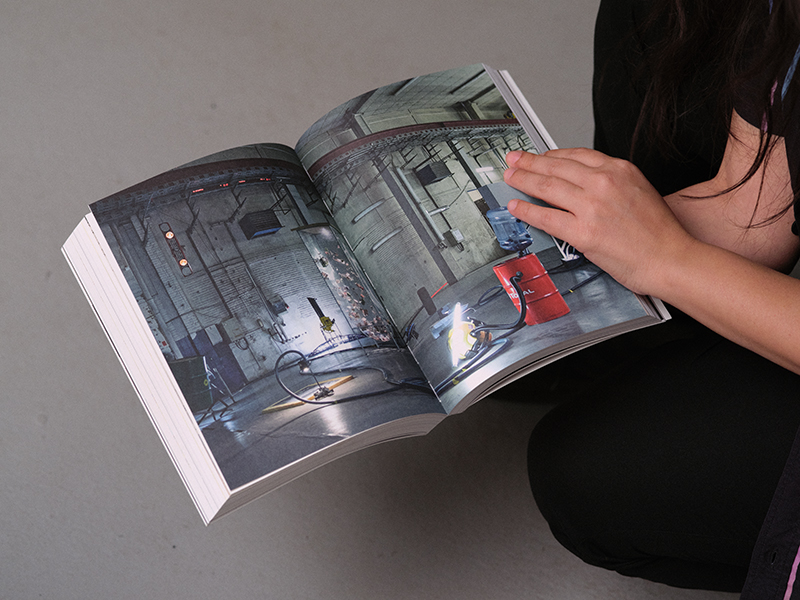

Her work-in-progress, ‘El resplandor los dejó ciegos’ (‘The Shining Blinded Them’), rests under an overhead window from which sunlight generously pours into the room. The artwork is set to be presented in the group show ‘Cabilla‘ at TEA Tenerife Espacio de las Artes in the Canary Islands—a project by Sol Calero exploring modernity in Venezuela that resulted from mass immigration from the Canary Islands, accompanied by a transfer of economic practices and images. Typical for Alenso’s practice, the artwork is a delicately balanced assemblage of industrial and mass production debris: metal rods, rubber hoses, fuel pumps, a couple of asphalt stones and upturned water bottles. “Water is always the most important,” she explains the latter, “not only for human bodies but for almost all industrial processes, so water is very vulnerable to contamination.”

Working with creative recycling processes and circular movements, Alenso aims to emphasize the connection between society, natural resource extraction and pollution. The rotating objects and closed loops of matter flowing through the installations materialize the artist’s preoccupation with the ways in which man-made systems work, and how we can collectively escape their devastating circuits. “I aim to provoke an experience, a reflection; to reveal alternative narratives around current and historical socio-ecological scenarios, which arise from the very materiality of the objects,” she adds.

A problem-solving inventiveness is the backbone of all her pieces. Conceptual connections and symbolisms unravel from heaps of waste that the artist transforms into perfectly balanced vessels. Her work is very physical, asserting its presence through size, movement, tension and noise. Tension reflects the instability she finds in the world around her and consequently within herself, while sound counterpoints the raw materiality of her constructions. The latter often comes from objects animated by airflow. Similar to working with water, Alenso incorporates the movement of air in her installations as it is “in a way alive, unpredictable, there are no guarantees that the work will remain the same during the exhibition.”

Alenso shows us a few of her other sculptures spread across the studio, ready to be packed and shipped to the next exhibition. This past year has been an incredibly busy year for her with shows lining up one after another: at Nkrumah Volini in Tamale, Geneva Biennale: Sculpture Garden, nGbK in Berlin, TEA in Tenerife, KAI 10 Arthena Foundation in Düsseldorf and Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, just to name a few. For 2023, she is planning a new commission for the next edition of Werkleitz Festival that will deal with post-mining landscapes and mentalities in Mansfeld County in Germany and comparable regions around the world. She is also about to publish her first publication, ‘What The Mine Gives, The Mine Takes,’ focusing on the recent expansion of the mining conflict in the Guayana and Venezuelan Amazon regions. It is the result of extensive collaborations with Venezuelan artists, filmmakers, poets, people of the Indigenous communities, as well as scientists and activists. Having these kinds of periods as an artist is great but challenging, Alenso admits. The issues to which she dedicates herself—economic crises, failed political systems, the brutality of colonialism, the avarice of capitalism, extractivist wreckage, ecological collapse—must be taking a toll, as well. Many of these difficult topics relate intimately to her Venezuelan identity, forged more fervently in self-imposed exile.

Alenso’s artistic language has been identified as “petrocultural imaginary,” pointing to the way she addresses the consequences that the petroleum industry has on all aspects of society and the environment. A Venezuelan who moved to Germany in the wake of the worst economic crisis in the history of her home country, she astutely communicates, through her artworks, the implications of the over-extraction of oil and other resources. Her multimedia installation ‘1,000,000%’ (2015-2018), titled in reference to Venezuela’s recent hyperinflation that rendered gasoline more affordable than a bottle of water, collates found objects as building blocks of a four-dimensional scene that engages (or rather aggravates) the senses, to capture the idea of a system in crisis. Recreating the once popular lottery game ‘Ciclón del dinero,’ the airflow coming from a leaf blower tumbles useless Venezuelan bolívars inside a plastic booth and gradually shreds them into dust. The ear-piercingly loud mechanism is joined by the panicking voice of a Chicago Stock Exchange broker blaring from a speaker placed in a pungent oil barrel. The interconnected pieces of the installation become associated with the larger picture; brutality and fragility take turns reflecting the tragic failure of capitalism.

There is a phenomenon at play, known in political economy as the “resource curse” or “the paradox of plenty,” which describes how countries with natural resource wealth have lower economic growth and worse development outcomes than countries without it. “It is one of the concepts I really identify with and from this point of view, I understand a lot. Resource richness doesn’t lead to the richness of the people, but rather of the government, reinforcing authoritarian regimes, corruption and violence. This is clearly happening now in Venezuela, but the history of oil is long.” Alenso continues to explain that Venezuela—the “Kuwait of Latin America”—has the first big reserve of oil. However, the so-called resource curse also affects Chile and Ghana—places where the artist had the chance to engage with the local workers and activists and produce art related to the issues affecting their communities—as well as many other countries around the world. “Oil is everywhere. We’re totally dependent on it. It’s hard to imagine the world without it.”

This sentiment is perhaps most explicitly thematized in her artwork ‘Medusa Fossil Addiction’ (2021), which was presented in the exhibition ‘Metabolic Rift’ as part of the Berlin Atonal 2021 festival at Kraftwerk Berlin. For this occasion, Alenso created a large revolving installation with diesel nozzles, strands of synthetic hair and asphalt stones attached to long chains—a modern, industrial twist on the ancient myth of Medusa. Suspended from the ceiling, it functioned as an amulet foretelling the fallouts of our collective dependency on fossil fuels.

Despite the severity of her work, Alenso strikes a light and cheerful tone. As we sink deeper into geopolitical issues, she pushes glumness away to emphasize the poetic and the imaginative in her creative process. “I am not so positive about the future,” she admits with a conflicted smile. “But I don’t want to be pessimistic with my art, either. On the contrary. I believe in the power of poetry and art to transform our vision of life.”