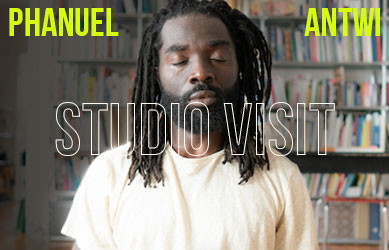

by Zoë Ritts, studio photos by Curtis Hughes // Nov. 10, 2023

“O my body, make of me always a man who questions!” says Phanuel Antwi, citing the closing line of Frantz Fanon’s ‘Black Skin, White Masks.’ It is late September. Antwi sits on his heels at the top of the marbled yoga mat that travels with him everywhere. His workspace is here, in the Prenzlauer Berg living room of an attic apartment that doubles as a studio. The rich timbre of his voice fills the humid air like an embrace. This afternoon it subdues a 15-month-old gazing at him on wobbly legs, brought along by her mother. Antwi is a natural orator, the kind who can captivate a room of 80 people.

Antwi is an associate professor at the University of British Columbia and Canada Research Chair in Black Arts and Epistemologies, but has been traveling to and from Berlin for the last 12 years. He is also an activist and artist, working with dance, poetry and the overlapping field of somatics, as well as (moving) image. “When I’m in Berlin, the neighbourhood becomes my studio,” he explains. A ritual of criss-crossing walks in the city’s eastern areas last year, during a particularly dark winter, inspired the forthcoming essay collection ‘Gifts of Lichtenberg.’ Walking is not an empty gesture: it is catharsis and methodology, “an embodied art of practicing freedom.” This is rooted in Antwi’s background in dance, which began in highschool. There, he tells me, he came to favor embodied poetics—as opposed to oppositional politics—as a way of moving through the world.

Like many of his projects, ‘Gifts of Lichtenberg’ is the trace of a movement, captured in fixed form. Process is at the core of Antwi’s practice, its primacy helps resist any singular reading of his artworks or poetic works and any sense of finitude within them. Instead, his whole oeuvre can be understood as dealing with and channeling through movement: even when at rest, dreams present a dynamic moment.

Throughout our conversation, we circle back to the processing of knowledge through embodiment, with a special nod to the body in historical, haptic and political formation. In mid-November, Antwi will launch his most recent work ‘On Cuddling: Loved to Death in the Racial Embrace’ (Pluto Press, 2023), which slips between essay and poetry, wrestling with the entwining of racial violence and intimacy. The book’s title suggests his interest in the relational: it takes two to cuddle.

For Antwi, the Black and diasporic body, even the collective Black Atlantic and Pacific body, is a cipher to the world. It is a means of thinking-through, situating his practice within the lineage of the pioneering Black studies tradition. Fred Moten and Stefano Harney’s concept of “hapticality” contrasts with the western, European, white epistemology that severs thought and feeling. Instead, hapticality insists on an aesthetic and a political formation informed by the overlap and suturing of this break. With an image of the slave ship’s hold in mind, Moten and Harney assert that hapticality is “a way of feeling through others, a feel for feeling others feeling you. This is modernity’s insurgent feel, its inherited caress, its skin talk.” It is knowledge obtained through the senses, shared through sweat, passed through pores.

I bring us back to the yoga mat, fingers fanned out on its rubbery surface, to ask which raw materials and objects inspire new work. For an ongoing work about soil, Antwi covered his living room floor with dirt and recorded the sounds of walking through it. The sound recordings and tactile memory of direct contact with soil were the process of coming to know the material, a necessary means to create what might later become a poetic work. “You don’t get to see what I do to make the writing,” he tells me, “the writing is born out of doing things.”

His poems thus become a private notation—the compression of thoughts that might be revisited later, but they are also inherently pluralistic. In the economy of the poem, there also exists open and invitational space for the reader’s interpretation. Meanings are “few and many at once,” similar to the unbound nature of his artistic practice, with its outputs in image, text, or gesture. A political undercurrent winds through our conversation, and calls to mind Walid Raad’s wary titular phrase “scratching on things I could disavow”—the admission of a hesitant or provisional engagement, but a necessarily physical one nonetheless.

“The doing is the thinking and the thinking is the doing,” Antwi tells me, drawing the cycle by tracing a loop in the air. At the University of British Columbia, he and his research team have founded the Studio for Racial and Colonial Tidalectics. Their concern is not only with the Black Pacific—contributing to studies of the Black Atlantic after Paul Gilroy—but with the experiences encoded in waves of contact against the flesh and bones of the racialized body. ‘Tidalectics’—borrowing from Barbadian poet and academic Kamau Braithwaite—“is an invitation to think about the archive and history as something that is never fully graspable, as a wave.” The ungraspable can’t be fixed or finished—a wave is pure process.

We’re on oneiric terrain; we’ve left the yoga mat behind. In 2021, Antwi returned to Berlin for a residency at transmediale. For that year’s iteration of the festival, he and his collaborators Max Haiven and Cassie Thornton had a studio space at Silent Green and used it to work on their ‘Strange Bedfellowship’ project. Their project goes against the world-destroying system of colonial racial capitalism that insists dreams are simply worthless brain noise or personal inspiration. They take solace in ways that civilizations around the world and throughout history have found dreaming invaluable, especially when it can transcend individualism and become a collaborative practice. Antwi, Haiven and Thornton mostly used the space at Silent Green for sleeping. “We would nap together,” he says, smiling. “In order to dream.” They invited others to join them and sleep away the afternoons in collaboration.

As part of the transmediale’s 2021 festival, the film programmer, Ben Evans James, commissioned work from Antwi and filmmaker Rhea Storr. They created a two-channel film installation, ‘For the Record’ (2021). The result is a decidedly dreamy conversational incantation between Antwi and Storr about memory and diasporic space. In the installation of ‘For the Record,’ grainy, sleek, streaky, black-and-white images of London and Vancouver flicker to life on two screens under their guiding voiceovers. Nighttime photos of harbours, rainy highroads, over- and underpasses, alleys and apartment towers appear and recede. Images of significant historical sites are there, too: London’s Black Cultural Archives, the former site of Olive Morris House, Windrush Square and Vancouver’s English Bay, Hogan’s Alley area and the Georgia Viaduct erected on top of it. ‘For the Record’ is a visual archive of histories, illustrated by the spaces of their absence. The two screens of the installation face each other in a conversation, leaving the audience in between, unable to see both at once in an experience of split perception.

The pace of ‘For the Record’ is a resting heartbeat. It pulses consistently onward, ducking in and out of history. Antwi has been interested in the rhythmic—breath, tides, steps and flow—long before ‘For the Record,’ and long before his 2022 Marshall McLuhan Lecture on media. For that lecture, entitled ‘Anticolonial Dreaming: The Elemental Poetics in Dub,’ Antwi turned to the beat of experimental music emerging from Jamaica in the 1960s and 1970s to further explore his interest in dreaming, suggesting that dub poetry inaugurates a method for anti-colonial dreaming, “one that insists that dreaming is not a passive activity that happens at night.”

We end our conversation about Antwi’s varied practice by situating ourselves in the present again: he notes that his work always begins with a daily walk around the neighbourhood. The repetition of his own daily rituals are seen by Antwi as a practice of alignment, an effort to “syncopate the senses as systems of knowledge.” This creates an arrangement that is harmonious but still acknowledges displacement, disturbance in the regular flow of rhythm. Dreams can be that syncopating beat—an interruption, towards other worlds and futures. Or, dreams can wake us up to existing realities and radical awareness.

In another film from 2021, ‘FKA Sort Of,’ Antwi and collaborator Lesley Loksi Chan sit at a wooden dinner table, framing the Canadian poet Lillian Allen. Allen reads from a book of poetry, reciting words that seem to summarize Antwi’s practice-as-process best: “but Oh. Oh oh oh Oh! Oh! Ooh! Your smile provokes a poem in me, and I would love to make a revolution with you.”

Exhibition Info

Savvy Contemporary

Phanuel Antwi: ‘On Cuddling: Loved to Death in the Racial Embrace’

Book Launch: Tuesday, Nov. 14, 2023; 7:30pm

savvy-contemporary.com

Reinickendorfer Straße 17, 13347 Berlin, click here for map