by Alison Sperling // June 20, 2023

This article is part of our feature topic Aging.

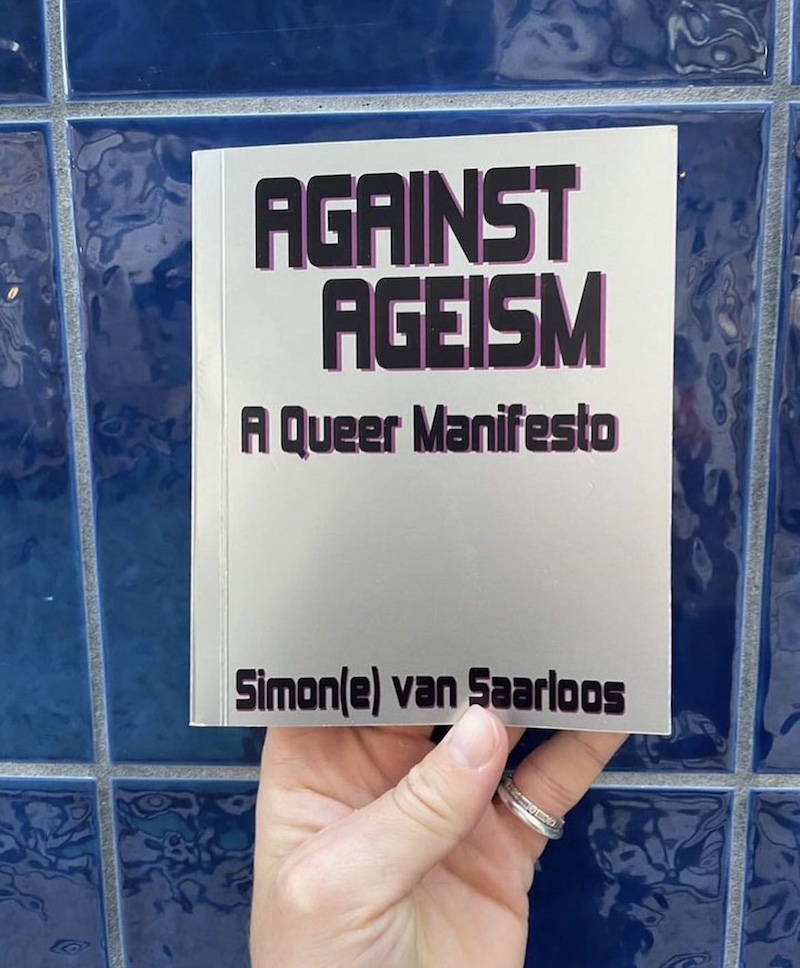

Simon(e) van Saarloos is a writer, artist and philosopher based in Amsterdam and in Berkeley, California, where they currently pursue a Ph.D. in Rhetoric at UC Berkeley. They are the author of ‘Playing Monogamy,’ ‘Take ‘Em Down: Scattered Monuments and Queer Forgetting’ and, most recently, ‘Against Ageism: A Queer Manifesto.’ Though only their most recent book outwardly claims itself a manifesto, van Saarloos’ dynamic work across their writing, curation, performance and activism is always as spirited as it is seductive. Their other recent works maintain their sharp focus on dismantling racism, ableism and structures of colonialism and whiteness in projects that draw from the often queer communities in which they are situated, including ‘Cruising Gezi Park’ and Rietveld Academy’s Studium Generale, multi-year transnational queer community, nightlife and art project ‘Through the Window.’

‘Against Ageism: A Queer Manifesto’ was recently published with Emily Carr University Press (2023) and will launch in Berlin at Hopscotch Reading Room on July 27th. We spoke with van Saarloos, in a written exchange over the course of a few days, about the book and about how age and ageism inform their thought, as well as their artistic and curatorial practice.

Simon(e) van Saarloos, portrait // Courtesy of the artist

Alison Sperling: I’d like to begin by asking you about the origins of ‘Against Ageism: A Queer Manifesto.’

Simon(e) van Saarloos: I was generously invited by Vancouver-based publisher Kay Higgins to contribute a manifesto to her ‘Reflector’ series at Emily Carr University Press, and immediately knew it had to be about ageism. I’ve been working with questions of the colonialism of linear time in most of my previous books, and I’m now engaging more with the ways time is mapped onto the body. We are all assigned an age at birth. From then on, the normative timeline that we call age, decides what is normal for you, whether you are ready for certain things and should be protected against others. I draw from many different people who think about time in relation to race and access, for example, asking: who has access to time? The longer life expectancy of white people is a question of access, and the patterns of expected behavior and development according to age, are arranged to further privilege and reinstate the centralization of white life.

While feminist theory allows for an analysis of power, queer theory further de-naturalizes everything and anything that seems even remotely self-evident. Queer theory, and especially queer of color critique, has done a juicy job of twisting time, of questioning the naturalized forward flow and sharp distinction of developmental phases in children and adults alike, of destabilizing the division between adult and child, of derailing time as a progressive and reproductive rhythm.

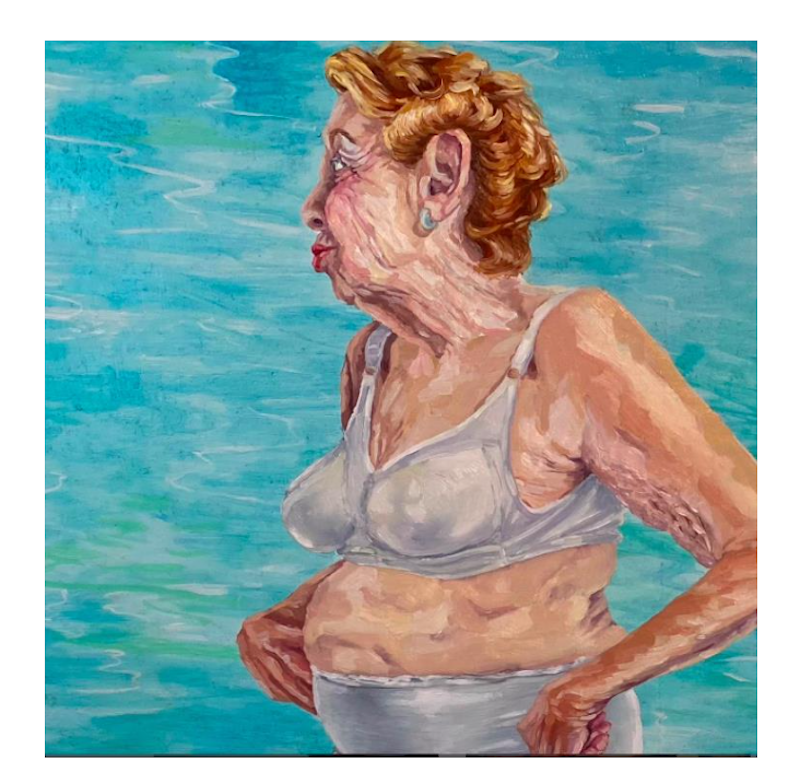

AS: Details from artist Samantha Nye’s works ‘Piss Pool’ (2021) and ‘1-800-FLOWERS’ (2020) bookend this text. Can you talk about the various artists that you draw from in this work about ageism and in other work you personally do in your practice and activism that also operate against ageism?

SvS: Samantha Nye’s work is fantastic, especially as she works inter-generationally, collaborating with her bio mother and grandmother without safely desexualizing them. Nye plays with the doubling effect of her and her mom looking alike, but the familiarity of their image is not safeguarded from eroticism: they are lusting over the same people and participating in the same play scenes. Nye’s serious engagement with queerness and age is playful. I believe this is the strongest approach to queer and trans-ness at the moment. Not to defend its reality, its existence, its naturalness, but to refuse to defend our existence and intimacies altogether.

Samantha Nye: ‘Piss Pool (detail),’ 2021, oil on canvas, 66” x63.26″ // Courtesy of the artist

AS: You’ve curated Nye’s work elsewhere. It’s really productive and joyful to think about aging as abundant in the way you framed it for that show: it shows aging outside of age as the (mere) accumulation or ownership of time. Is abundance, besides operating as a philosophical framework for you, also a stylistic or methodological choice? ‘Against Ageism’ is a slim book, but it’s packed with references and ideas from across academic disciplines, artists, and activist and social circles.

SvS: Abundance is definitely a methodological ambition, a strategy to continuously strive for a spilling over, an enforced redundancy of the categories that seem useful and are often perceived as natural or evident, such as time and age. Abundance also shows up in the writing itself. I try to have a non-monogamous citational practice that allows for scatter and non-linearity, countering the academic fidelity to lineage, performing completeness and approaching discipline as totality, longevity and loyalty. Sometimes citation is collaborative, a mutual exchange. Sometimes it is an invitation for future comradery. Sometimes it’s simply to show you are not alone. Sometimes citation is without a desire for reciprocity. Sometimes citation is submissive, desiring to see where the work takes you.

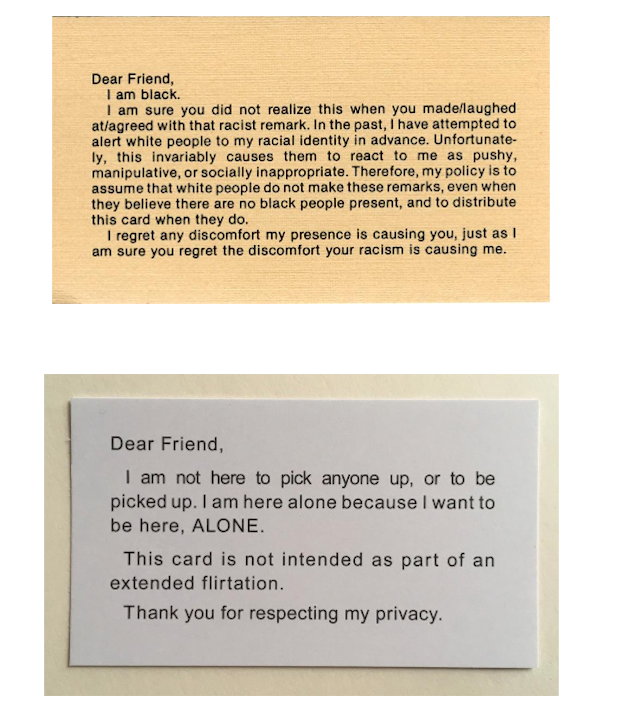

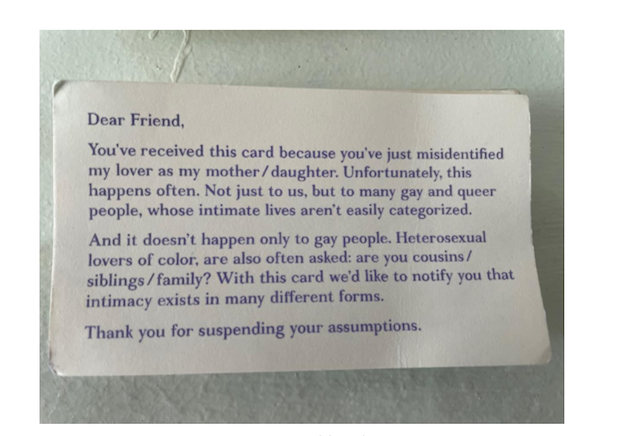

Adrian Piper: Performance prop: brown printed card. 2″ x 3.5″ (5,1 cm x 9 cm) // Courtesy of Collection of the Adrian PiperResearch Archive (APRA) Foundation Berlin, © APRA Foundation Berlin and Angry Art

AS: Tell us about some of the other artworks included in the book.

SvS: Adrian Piper’s ‘Calling Cards’ (with generous admission from the archive in Berlin) are also included in the book. These calling cards formed an inspiration for me when trying to figure out how my 60+ partner and I should respond to constantly being addressed as mother and child. We would be kissing and still people would say “how nice you are here with your mom.” Piper’s calling cards taught me to flip the script by having these cards that say: “Dear Friend, you have just misidentified my lover as my mother/daughter.” Instead of shaming our extraordinary presence, their ordinary and predictable attitudes are on display. These cards teach me abundance too, as they challenge me to read people as queer couples, even though they might just be mother and child. Allowing this fantasy and projection, public spaces become much more queer, juicy and livable.

AS: What kind of responses did you receive when you handed people these cards?

SvS: When you’ve been identified as mother and child, you’ve been placed in this supposedly “innocent” category of “the Family.” Coming out as a couple after having been read as family brings the thought and taboo of incest to mind. The hostility that you meet when coming out is countered by the card, because having produced and printed the card puts the receiver in an apologetic position. It’s fun to watch! The partner—“Mother” in the card—and I broke up, but others in intergenerational relationships have asked to use the card, and I’m sure I’ll be having to use this card again. I’m now thinking with some folks about a phrasing that addresses invisible disability and assumptions around fatness.

Adrian Piper: ‘My Calling (Card) #2 (Reactive Guerrilla Performance for Bars and Discos),’ 1986-present, performance prop: printed card. 3.5″ x 2″ (9 cm x 5,1 cm) // Courtesy of Collection of the Adrian Piper Research Archive (APRA) Foundation Berlin, © APRA Foundation Berlin

AS: I want to ask you about your provocation in which you write: “I wonder whether opacity regarding age wouldn’t be a stronger form of anti-ageist resistance. What if we refused numerical age…?” What are some ways you imagine the question (asked mostly of women, as you note): “How old are you” being reframed and in what context? Or, what are some anti-ageist ways of responding to questions that attempt to center age?

SvS: This is a great question. My skepticism is, of course, of the promise of certainty that comes with calculation and numbers. What does one expect to know or have access to, when revealing one’s age? I don’t think opacity regarding age is just about responding to assumptions. We should literally refuse to be classed according to age; in schools, learning environments, dating apps, on passports. Legally, the world is very much divided by age. Why do we normalize age related voting rights, holding on to the idea of increased rationality and stability, while ignoring the fact that those who are distributed a lower life expectancy have less access to dismissing the institutions that neglect their well-being? Why do we expect the age of consent to be protective enough while letting the white nuclear family off the hook, even though for some if not many it is the most dangerous and confining place? Why do we celebrate laws against child labor but allow companies to create murderous labor conditions for those 18+ and rapidly increase the age of retirement? Why do we have juvenile treatment, but still allow for prisons? Why can white boys be boys at 50 years old and Black teenagers are treated as adults? Age needs to appear as a natural category, to disguise the fact that there is no universality to age at all.

Simon(e) van Saarloos: ‘Against Ageism: A Queer Manifesto,’ 2023, cover image // Emily Carr University Press

AS: Did you have any concerns releasing this book with regard to its content being perceived as too radical? I’m thinking about two places in the book in particular. The first, in the chapter you reference above with the calling cards, where you question the forms of intimacy we have with our family relations. It’s quite an important observation, I think, that if we are invested in expanding notions of the family (or abolishing it altogether, following Sophie Lewis) as a queer political project, this also necessitates a revisiting of the boundaries of intimacy between familial ties. The second moment is your disclosure of an experience of sexual assault as a child, and your focus less on blaming the perpetrator and more on the harm that age as a category does, when, for example one is constantly treated as not being “old enough.” Are you comfortable talking a bit more about either of those issues or more generally about if anything felt especially dangerous about some of the claims you make in this book?

SvS: I don’t push through fear to write, I display a very simple and sensitive unease with existing limitations. I just don’t get why things are the way they are. That doesn’t push me to provoke, it pushes me to find community.

Everything is a material question for me: books are not a moral or sacred product, they are objects in a hyper-capitalist world of scarcity. I have been extremely lucky and privileged (considering my history as a white person in the Netherlands) and it’s through such material access and distribution that I view my ability to write and speak, and not through the lens of freedom of speech and bravery. Ultimately, I’m interested in the possibility of writing and speaking without defense. So, how to continue while subjugated to criticism, without defending the value of what one has to say? This is the trans question, too, right? How to refuse being subject, being subject of any debate, without claiming a right to exist, without demanding inclusion into fucked up structures of normalcy?