by Dagmara Genda // June 27, 2023

This article is part of our feature topic Aging.

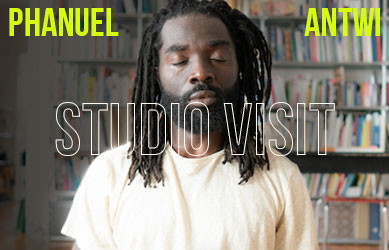

Laurel Nakadate’s work has a lot to do with time and the necessary changes that come with it. In the early noughts she became well known for provocative, strange videos, such as ‘Oops’ (2000), which she staged as a 20-something in the homes of older men she met by chance on the street. The ironic, strangely tender and ambiguously exploitative works were possible because of her youth, as was the media’s sometimes aggressive reaction. Since around 2011, the artist has moved away from featuring herself in the starring role—not least because her “body was up for discussion at all times,” as she explains during our interview—and started to focus on extended notions of family, though in a rather elegiac and melancholy way.

Life, death and the interminable forward push of time characterise her videos and photographs which, perhaps more than other mediums, are markedly temporal. Technology changes visibly and how we represent ourselves with and within it changes as well. To this end, Nakadate makes use of vernacular images and the visual possibilities of the day, such as enlisting the services of internet photo editors, to document and contemplate the passage of time. How time and age have affected the artist and her work is what I set out to find out in our recent conversation.

Laurel Nakadate: ‘Oops!,’ 2000, 3-channel SD video installation, color, sound 3:42 min, video still // Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Tanja Wagner

Dagmara Genda: Has the perspective of time affected how you view your early work?

Laurel Nakadate: When I made all that early work, I made it because I was thinking about the lives of my great grandmothers who came to America as picture brides from Japan. I was thinking about the chance encounters that led to the relationships formed with the men they eventually married. They were brought to American based on a single photograph of themselves. They married a man who chose them to come to a country they had never been to, to live in a country that didn’t want them.

I don’t feel that was discussed much in the early work. People weren’t spending a lot of time talking about race or the reasons I wanted to make that work.

DG: It’s interesting that you talk about relationships through pictures, because there is more of that today, isn’t there? Many young people are on Tinder before having ever dated. Their introduction into relationships is …

LN: … is through images, yeah. And through the value of images as a currency to create emotional space for one another, or to maybe not create emotional space.

We have been using photographs in this way since photography was invented. Sometimes I wonder—and maybe this is just because I’m old! [laughs]—if individual photographs matter to young people as much anymore. Does the disposable quality of photographs on the internet make them placeholders for emotions, or do they hold this sort of weight and currency that they held when we were young? Now we scroll so quickly, sometimes I wonder if young people really break their hearts over an image anymore.

DG: Today the image has replaced reality and people could have a relationship just through images. Do you think the image back then had a different connection to reality?

LN: Absolutely. I also remember the scarcity of images. You only had 36 images on a long roll of film. Maybe half would turn out the way you wanted them to, maybe only a quarter. Now, the roll never ends. I sometimes wonder if there is still that level of longing. I fell in love with photography because it created a space for longing.

Everything is so balanced now, perfectly sharp and clear. There is no real depth of field. I think of depth of field as a space for emotion in a photograph.

Laurel Nakadate: ‘Oops!,’ 2000, 3-channel SD video installation, color, sound 3:42 min, video still // Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Tanja Wagner

DG: Since 2011, you are no longer the main protagonist in your work. Why did you turn the lens away from your own image?

LN: Young female artists are often attacked for their physicality. My body was up for discussion at all times: in shows, in interviews, in talks. Part of that, of course, was put in the work on purpose. I wanted to have a discussion about young, female, Asian bodies and the ways that society views those bodies. But part of it was also the misogyny of the late 90s early 2000s art world. I reached a point where I wanted a break from that.

Laurel Nakadate: ‘Tucson #1,’ 2011, C-Print, laminated with UV protective flm, back-mounted on plexiglass, 101.6 x 152.5 cm, 104.1 x 155 cm (framed) // Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Tanja Wagner

DG: Do you shoot digital or analogue?

LN: I do both. I use digital when necessary. ‘Strangers and Relations’ was made with strangers at night under darkness and had to be shot digitally so that I could setup in darkness more easily and travel great distances with little equipment. I find myself going back to analogue technologies more recently as an insistence on slowness. I want to slow down.

So much of my work is about time: time changing how we view the work, time changing the way we view ourselves. In ‘Strangers and Relations,’ I opened the shutter for more than 30 seconds sometimes, so despite being digital, it was about this long exposure at night, being still with someone in the darkness. It was about the ways we can measure lives in small moments or increments.

DG: A lot of your projects seem to be long term.

LN: I started the ‘Relations’ series in 2011 and I am still working on it. I completed what I hoped to complete on my mother’s side of the DNA project, but now I have started to work on my father’s side. When I first started on that project, consumer DNA testing in America was in its early stages. I only had a few matches on my father’s side. Japanese Americans make up less than half of one percent of the U.S. population. I e-mailed all of my matches on my father’s side, and only a couple of people replied. Now that DNA testing has caught up, I have started to work on his side. That project could span 20 years. Long-term projects are something this medium is well suited for anyway—to tell a story over time.

Laurel Nakadate: ‘Kalispell, Montana #1,’ 2013, C-Print, laminated with UV protective flm, back-mounted on plexiglass, 76.8 x 114.7 cm, (framed) // Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Tanja Wagner

DG: Can you reveal a little about your upcoming multi-year film project?

LN: I am working on a project about my great-grandmother, who married multiple con-artists during her lifetime. She found herself in marriages with men who concealed their actual identities. It’s a long story and will probably take years for me to unravel. I started it before the pandemic and am only now about to pick up the thread again.

DG: There seems to be a shift in visual vocabulary with the explicit focus on family. It becomes more elegiac and maybe even sentimental. Do you get that sense?

LN: I definitely get that sense. The work of youth is to disrupt life and I think the work of middle age, or whatever this time I am in, is maybe to participate deeply in what is in front of oneself. I feel so lucky to even experience this moment. I love that the job of someone in their 20s and early 30s is to be disruptive—to flip over everything, to look underneath everything—and now there is this moment when things can be more measured, but also incredibly profound and deep.

In ‘The Kingdom,’ the project made right after my mother died, there was just no other choice but to tell this heart-breaking story. This was in 2018 when I made that work and the art world wasn’t talking about motherhood at that point. I was really, really worried about showing that work, but the profound grief that I felt gave me the courage, or perhaps just the lack of other options, to show it. That was the only work I could make back then. I was at my mother’s deathbed with my newborn. How do you process that kind of experience?

Laurel Nakadate: ‘The Kingdom #10,’ 2018, C-Print, 9 x 12.7 cm, 37.3 x 30 x 2 cm (framed) // Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Tanja Wagner

DG: You are usually very purposeful in how you compose an image, but here you chose to give up control of your aesthetic decisions to people who usually are hired to make you look thinner and have whiter teeth.

LN: It all started because of a spam e-mail for photoshop services. In the e-mail they wrote: “we can fix anything.” I responded and asked if they could fix these photographs of my mother and son and the fact that she had never held him. Their first response was that this project might be too difficult. I asked them to please try and wrote that I will accept any outcome. Then they started sending me pictures of my son in my mother’s arms. The photoshopping is just terrible. But that’s what is amazing about it. The process and outcome reflect the emotional space I was at in that moment, the impossibility of my request and the limitations of technology.

Laurel Nakadate: ‘The Kingdom #30,’ 2018, C-Print, 12.7 x 16.9 cm, 37.3 x 30.3 x 2 cm (framed) // Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Tanja Wagner

DG: It seems only recently that motherhood is becoming a little less of a taboo in the art world. A pause in art making or articulating motherhood in one’s work does not automatically end the career.

LN: Yes, I feel that too. For me, it has been about building both a deep and expansive career, and also a fortified emotional landscape in my personal life, and hopefully, resilience in both spaces.