by Dagmara Genda // Mar. 28, 2024

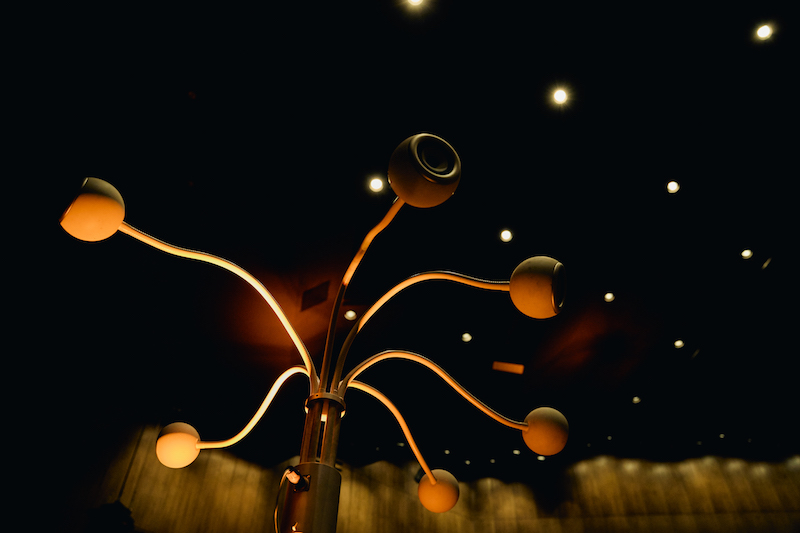

An opening concert consisting solely of about 60 loudspeakers might seem like a rather understated start to an international new music festival, but, in effect, it turned out to be strangely confrontational. François Bayle’s Acousmonium, first introduced in Paris in 1974, stared back, like so many unblinking eyes, at the packed house of Maerzmusik 2024 in the main hall of Haus der Berliner Festspiele. Each type of speaker, which also included six leering, alien, loudspeaker “trees” sprouting between the seats of the hall, emitted its own particular quality of sound according to acoustic dispersion capacity, sound colour and spectrum. The ones “performing” were spotlit by coloured light, but of course as objects, they kept unrelentingly still. And so it was a heightened sensibility to the acoustic moment as such—or, as Lucia Dlugoszewski, whose work formed the research topic of this year’s festival says in a 1992 interview, a “radical suchness”—that was central to director Kamila Metwaly’s perceptually-steered, yet also reflective, approach.

Acousmonium, opening of MaerzMusik 2024 // © Berliner Festspiele, photo by Fabian Schellhorn

Though conceived 50 years ago, the Acousmonium remains astonishingly futuristic, as was the music it “performed,” most of which is now historical, stemming from the original composers who formed Pierre Schaeffer’s Groupe de Recherches Musicales (GRM). In fact, it was the historical works that sounded most fresh in comparison to some of the younger composers. Beatriz Ferreyra’s ‘L’Orvietan’ (1970), for example, felt right in the moment with its mixture of electronic and concrete sounds, teetering on familiarity then blurring into surreality—a quality strangely parallel to the early visual evocations of text-to-image AI. And though Ferreyra championed the ethos of acousmatic music, which was all about non-referential sound, the start of her piece could be described as an army of bees with orchestral ambitions that gradually evolves into a world of feline wails to clarinet howls to some sort of bendy electroacoustic waves. The much younger Eve Aboulkheir and François J. Bonnet, in comparison, created dreamy atmospherics that seemed all too tinged by the subsequent years of electronic ambient innovation to which Ferreyra was not beholden.

Acousmonium, opening of MaerzMusik 2024 // © Berliner Festspiele, photo by Fabian Schellhorn

Of course, purely non-referential sound is now impossible after years of electroacoustic noise, vocoder effects, autotuning, feedback screeches and more. But what might still engender a sense of wonder is the recombinant flows that insinuate without fulfilling and anticipate without climaxing. This was the case in Lucia Dlugoszewski’s oeuvre, which seems to me a music of citations without references. Her sounds are words that sit at the tip of the tongue, about to give form to the notion struggling its way out of the body, but left only in outline, as something almost known. Dlugoszewski herself speaks of “radical otherness,” which she describes through poetry or as a “picture on its side”—something you already know but is made other in the moment. ‘Amor Elusive Empty August’ (1971/1979) was one of the many pieces created through her collaboration with the Erick Hawkins Dance Company, but which also stands alone as a musical work. It’s panoply of interconnected moments consisted of chords trying to lead to places to which they never arrived, and tiny snippets of what suddenly could have been Miles Davis’ ‘Sketches of Spain’ but instead shattered into sonic scribbles and piccolo screams. ‘Cantilever’ (1988) also contained a series of endings that never ended, competing glissandos and bending tones that were at times reminiscent of radio theatre or special effects. This was her way of breaking the emotion inherent in a pitch, she explains in an interview. Other strategies included rattling and ripping paper, as well as the lighting and extinguishing of matches.

‘Space is a Diamond,’ 1970, for trumpet solo, with a choreography by Edivaldo Ernesto // © Berliner Festspiele, photo by Fabian Schellhorn

This collection of effects was also on display on the closing night, which featured the Erick Hawkins Dance company. In a televised interview shown as part of an installation in the Maerzmusik Library, Dlugoszewski explains how she strove to create music for dance that was “equivalent to an opera,” that is, a major Gesamtwerk, not just an accompaniment for movement. In fact, many of the pieces featured in the programme were made in collaboration with choreographer Erick Hawkins, who developed his choreography in silence, focusing on movement as form. Dlugoszewski then analyzed the dance pieces to create an acoustic response, in conversation as well as in tension with the dancer. This was vividly on show in ‘Space is a Diamond’ (1970), a piece for dancer and solo trumpet. Also a poet, Dlugoszewski describes the piece in terms of “calligraphies of speed” wherein the “line flowers into a variety of oscillations including ¼ tone trills until it reaches a new concentration of tautness and finally severs itself…” These microtones, which she produced through augmentations in the trumpet and seven different mutes, fluttered in parallel with the movement of dancer Edivaldo Ernesto, whose body cut through the air in frenzied bursts of speed. An optical illusion, presumably due to lighting, caused a visual trail to follow his arm, making him look multi-armed for a brief fraction of a second, like a figure in a flip-book, animated to the sharp rhythm of his breath, like the whipping sound a thin rod makes when swung through the air.

‘teeth,’ 2024, MaerzMusik // © Berliner Festspiele, photo by Fabian Schellhorn

Coming from the visual arts, I can’t help but understand sound as material, similar to paint in its shades, textures, contrasts and malleable viscosity. It was precisely this tangibility that was heightened at Maerzmusik. Whether it was in older works like Helmut Lachenmann’s astonishingly three-dimensional ‘Mouvement (-vor der Erstarrung)’ (1983-84), where sounds rushed toward the audience only to be pulled back as if on an elastic band, or newly commissioned works like the playful but precisely structured ‘Gormod’ (2024) by Bethan Morgan-Williams or the flexible tonal combinations of Elena Rykova’s ‘A Sonic Corona to a Song Eclipsed’ (2024), the sheer stuff, or “suchness,” of sound remained consistently present. Other high points: the spongy layer-cake “drone” of Eliane Radigue materalised in a blockbuster bagpipe performance from Erwan Keravec and Laure M. Hiendl’s seamlessly fractured electroacoustic string quartet. In the end, it was a small video in Miya Masaoka’s ‘Refuge in the Vegetal World’ that summarised this range of experience for me. Though the show at Savvy was in part didactic and unresolved in its presentation, the ‘Adventures of the Solitary Bee’ (2000), a touching, even uncomfortable video with a buzzing violin soundtrack, drew a line back to the symphonic hum of Ferreyra’s ‘L’Orvietan.’ But Masaoka’s bee had escaped its disciplined army to roam across the landscape of a naked human body with other freedom-seeking rebels. Searching in a navel or struggling through pubic hair, the small bee engages in radical otherness, gathering new sensations that might just possibly reconfigure the tired structures of the same old world.