by Elizabeth Feder // June 28, 2011

We started by rummaging. There were boxes of bubble-wrapped paintings, binders thick with inspirational images, photographs and fragments, and two new canvases with beginnings applied in charcoal and paint secured to two opposite walls. I met artist, thinker, eager-laugher, Melissa Steckbauer in her Prenzlauer Berg studio, on a March morning to have homemade mango lassis, rummage through her past explorations of the social-sexual and the latency of erotic space, and to discuss the potentials of interpersonal-connectivity for her work in the future. Surprisingly (and quite happily), the interview ascended to a point of Cosplay…and a great exchange.

Elizabeth Feder: So this is an exciting time to speak with you; we’re looking at a body of your older work as you’re beginning to move into a new phase. You’ve typically worked in two different scales in your paintings: you have these smaller canvases and then much more expansive works. What are you investigating with the larger pieces as opposed to the more intimate, delicate frames?

Melissa Steckbauer: Well, it’s indicative of my emotional range, so the way that I work either requires that I be that big or that I be that small. The middle formats are just not comfortable, somehow. It has to feel really small: tender, delicate, intimate, private. Or it has to feel like I’m taking all of that intensity and power, and stretching it out over a larger surface. That way the works can communicate the intense, big, and bold or the tight, tiny, and sweet that I’m experiencing.

Have you always translated your interests into painting? Are there other artistic mediums that you work through?

I have a girlfriend that I’m working with at the moment who is a videographer and we’re doing some work together. It’s nice but it’s not my first choice because I’m not using my hands. When I’m working with video, I’m in front of the computer more and I try to avoid time with the computer. I’ve done sculpture, but for me it felt really wasteful because it was large and had to have storage. That was just practically and environmentally difficult. As a student growing up with a relationship to the environment, throwing away massive “whatevers” became a problem. So I haven’t done much of that since. However, there are other things as well. I like it all!

In a lot of your paintings, I see this digital language that comes through the paint. For example, the way some of the bodies become pixilated, striated or reduced to these emptied contours. On the one hand, there is this very classical approach to exploring sexuality, intimacy and the body but then it confronts this digital expression, which I find incredibly exciting.

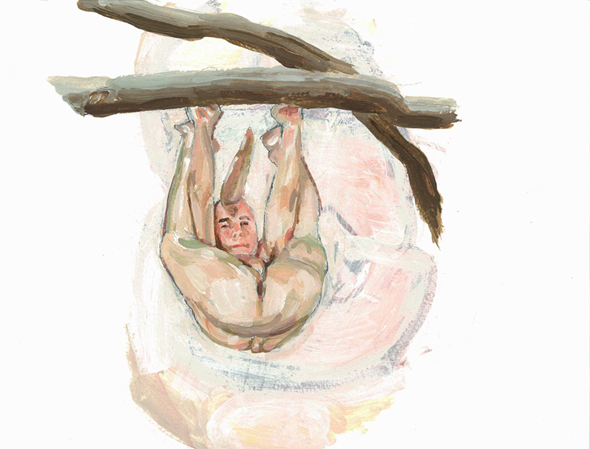

I like a lot of the classical handling: it feels very, very, very sexy, the way that paint was manipulated. While this is part of an old body of work, for me, the tenderness of flesh, the intimacy of touching bodies has to come through the paint. Now I’ve had to make a jump, but it’s so nice to talk about this earlier work.

I’m also thinking about the way that you place these figures. Sometimes they stand in a domestic setting, sometimes in an abstract landscape where everything’s open and there’s this explosion of limits. Do you see limits of physical identity? Do you see limits of the environments in which we place ourselves? Or is this something that is being disintegrated through art in the 21st century?

A lot of the people I know who are in the poly and queer communities, the alternative communities, and those who are politically-oriented, have very clear and specific ideas about identity. There’s this identity-culture, which is progressive and is changing from pre-identity, where there is no queerness or alt-sexuality (read: invisibility), there’s only one way or the other, and the “other” was usually shamed and excluded. Then there’s the hyper-identity thing, which is concrete and specific. I saw in The New York Times that there was a crop of folks who were doing this unclear gender-reassignment: maybe they were having their breasts cut, but they weren’t changing their genitals. There is this whole new territory for making a tradition by saying, “we’re going to cut, cut, cut.” Buck Angel, for example, is a man with a vagina. He kept his pussy but he cut off his breasts and he does gay pornography. It’s figures like these that take me into this other world. The same way that these identities create a new space, so do the differences between each individual. It was important for me to explore these specific conditions. If you enter a post-identity space, then there’s the issue of singularity. I’m interested in individuals as specific beings in specific bodies. Then it’s not about being body- or sex-positive, it’s just, “I have a body, I enjoy pleasure and I am going to work within this condition to deal with my body, my feelings and try to grow and develop.” Then if I cut, if I don’t cut, if I dress like a boy or a girl or however, if I mix it somehow, this is really revolutionary. Just to be a person, to go beyond all that other stuff. But that was a necessary step for people, this firm identity thing. But then there is the other issue of “energy.”

Here it becomes complicated on an immaterial level: the communication between intimacy and forms. So when people are experiencing each other emotionally, they’re dealing with intensity on an interpersonal level while not being super structured regarding language or intellect. We don’t feel emotionally safe with everyone and rarely take the time to carefully communicate with, for example, the clerk at the grocery store. Misconnected moments happen within intimate relationship as well, but again this foundation of self-knowledge, knowing the body and the emotional-self is where we can get to new territory with more people more of the time. That is what I’m trying to talk about with my work. If I get close, then I think I’m successful.

But this energy thing is probably the most interesting thing for me: the way that people are able to intuitively connect. There’s this magical condition where understanding happens. I think, generally, there’s a lot of misunderstanding in relationships, but the place where it transforms is in this kind of ambiguous space where there’s an open-heart, from at least one side, leading to an attempt or effort to connect. And that’s very sexy, that’s the sexiest thing. Then you can forget all the body-stuff. Forget all the porn, post-porn stuff. At this point, it is less relevant because it becomes about something connected, something honest and intimate. If you have any opportunity during the day to expose yourself to vulnerability and intimacy, then you can see how hard it is. It’s incredibly challenging to be so naked with the clerk at the grocery store, your boyfriend, your best friend, your mother. The energy is there when you have to say, “I’m breathing, I’m going to do this, I’m going to tryyyyy to be a whole person, I’m going to tryyyyy and be exposed and honest and really show up for life.” It’s incredible.

And this idea of the “ambiguous” space, you’ve really got to enter it. There has to be a deep willingness to pass over that threshold. I’m looking at the painting with the two figures on the bed, where that space is completely charged with the landscape and the body. Here, everything is articulated the same way. The space and the figures are so connected. The figures that you’re inspired by generally come from three different places. How do you negotiate between the pornographic, academic and personal sources?

Yes, the resources are from three different places: internet pornography/images, The Kinsey Institute, and friends and lovers. In the past, I’ve sought out people who were the most progressive and transcendent in their capacity for freedom: their capacity to talk about these things on a deeper level. Those folks are, in some cases, available to being shown and shared. But then I also sometimes work with friends, people who are not researchers or pioneers, but just people who are willing to be exposed. It’s always been organic and easy. And this became a part of the relationship, just to be able to play with this stuff. It was really fine to ask someone, “Can I photograph you? Can we do this project? Can we try that?” It was an entrance into a relationship. Sometimes, however, the relationship existed only at that level: that was the only space where it was possible to be intimate and engaged because we were both doing this work on this level, while daily kinds of things would fall apart. In a way, it’s like tight-rope-walking where you choose to walk this way and it’s very risky. It’s not on the ground. At the moment I’m trying to get more connected to the ground. In a way, I have to give up some of those progressive relationships in order to be more grounded.

When you say, “More grounded,” do you mean placing yourself in a different context? Are you searching for a different kind of expressive space?

I was carving it out this morning in my mind, because I was living in the atelier downstairs and it was big, empty, and spacious and it was at the ground level; the doors, the windows, everything was open and I would be painting these twelve naked guys kissing on the wall and everybody could walk by and see it. I was thinking, “Yes! Freedom! Sharing!” but I was ready for a change. This space is already different: it’s a space for a family. This is a different kind of world for me. I was thinking, monogamous, “hetero-normativity” sounds really nice for a change and it looks really good. It’s not the bohemian, super Poly, “I make love with my girlfriend and then my husband comes home…” but a very separate thing.

I’m still curious about, just going back a little bit to this older body of work, the process. For a project, you approach someone, and what happens? There is a connection that you’re exploring through painting, but there’s a personal connection that you’re forging. You have this relationship now.

Oh it’s intense, it’s passionate! I should say it was intense, it was passionate. Before, I would meet people who were peers. I would see them and say, “You’re a peer.” And they would see me and go, “You’re a peer.” It was very clear. Then when we catch each other, everything’s on the table. “Oh, I’m doing rope-work.” “Ok, can I photograph you?” “Yea, let’s go right now,” and so on, and so on. It just goes, like that [snap]! Some of the material that I have is from 2006 and I’m still looking at it…incredible.

But then other things are really safe and benign. For example, one of the subjects was another art student and clearly just a friend. On the one hand, that person was off-limits, but to play in a certain way was perfectly okay. This was part of a series of photographs where I was energetically dressing people up. In this case, I was literally dressing this person in my attire. So we went to my apartment, I dressed him up in all my clothes or he dressed himself up. It was totally free. He was the most amazing visual subject! He was so tender, so dear, and it was because his sexual appetite was so low in front of the camera that I was able to play with whatever he gave me. It became this stretched-out, beautiful exchange. I look at it now and all my queer boyfriends say, “Yea, wow, he is wonderful.” It’s because he’s in this really nice space between male and female energy, where he’s soft but he’s still very male. He’s something else.

This is where you get into the question of how do we speak about this post-identity condition where nobody is really male or female. Here it gets complicated. Within certain structures, such as the queer community, there can exist a super-clear identity thing. There is this, “I am they. I am not he or she. I am post-gender.” Then you might have folks in the yoga and Tantra communities who are recognizing male and female energy as distinct and separate, but they seek balance and symmetry. Then there are the BDSM communities with a total amalgamation of forms: role play, gender, power exchange, defined identity, switching, etc.

And then many of these issues deal with an intersection between human and animal experiences. There are these complex identity explorations that are not only supremely human (even emblematic of a 21st century understanding of humanity), but also coming from very primal, animal desires. The “animal” enters your work very provocatively, in many cases as a mask for these human figures. How does the “animal” become a part of the figurative story?

It’s very old iconography that I’m dealing with, and many artists have drawn from this imagery. It’s very popular, and it’s satisfying to play with those relationships because there’s something that we are missing in our raw communion with each other. I went to a Grinberg session recently and I felt like I was at the zoo: there was growling and pawing. You know Grinberg? It’s like therapy but they don’t construct it as therapy. But I felt like I was at the zoo. I was with this person, who was male, and it was like, “arrrrr-ack!”

[Laughter] A connection is made in letting these indefinable things out.

[Laughter] Yes! It was fun and I recommend it. It was totally noninvasive. I had all of my clothing on. There was no sexual energy but there was this other experience, kind of like wrestling. But I was not used to being on the side where I don’t have the control in the situation. I became really vulnerable; I was vulnerable in that moment. It was animal. It was so animal.

How many people were participating?

It was just me and this other person. But there is another thing you can do which is called “play-fighting,” which they have at Schwelle 7, a BDSM dance studio in Wedding. The way I learned it, “play-fighting” has essentially no strategic rules except, of course, that you’re not supposed to “intend bodily harm” to the other person. So it’s basically just wrestling, but you can bite and you can pull hair, you can do all these things that you’ve always wanted to do! It gets pretty raw. It was truly incredible because, deep down, there was this more gentle, “we’re just playing,” level.

I also tried women’s boxing (they have this in Kreuzberg). There was that similar animal energy except that there’s a clear structure. There are rules and you’re training to learn this “one way.” Grinberg is more like therapy; it has a more open, healing component where the intention is to get you more into the body.

I’m looking at this new piece you’re working on and I all I see is this Pangaea-world: instead of the continents drifting apart, here they are colliding. You’ve lived and worked all over the world, from Germany to Japan, and you’re tapping into very culturally specific ideas about the body, sexuality, and the relationship between social, sexual and emotional intimacy. How did placing yourself in all these different contexts affect your work?

Firstly, especially in Fukuoka, Japan, I met just the nicest, most generous people. I was doing a lot of research on the sex industry there: searching things out but mostly looking up things online, and what I discovered was super creative. It was like the working of soy in Taiwan: there are a thousand ways of handling a thing. Mostly it’s costuming: it’s really theatrical.

In the end, I really don’t have a clear sense of what sex is like in other parts of the world. In my experience, there are not enough people like Alfred Kinsey, who did research all of his life and was completely informed on everything he did. However, maybe his method is not the best regarding sex and sexuality internationally: Kinsey was a biologist and perhaps it’s not so great to be investigating everything all the time in such a standardized way. Still, he was brilliantly thorough, and I have a feeling that the relation to intimacy changes so much from culture to culture that it is important to know about it locally and in depth. What is it like in regard to language and social cues across cultures? What are other peoples’ relationships to the body? What are women’s relationships to themselves? What about expressions of autonomy in femme desire, and what do they look like now and historically?

These things cycle through time and I would like to see a greater representation of this kind of research. I don’t have the drive to investigate this in the same way that somebody like Kinsey investigated sex in America as well as he did: he was ingrained in it. I’m not interested in sex, really. Yes, it’s interesting, but I’m interested in power: emotional, relational, etc. Sex is one of the filters. As much as we have been able to scratch the surface, there is so much legwork to do. Perhaps there is a complicated ethical component in doing this kind of biological investigating, but I am curious. So I researched, I saw things and said, “Ok, I have to integrate this and think about the meaning.” Like so many things, it’s not so different from The United States but then it’s very different from The United States…

But as the idea and experience of “intimacy” is transformed by the many ways people connect today, your work communicates the power of these intersections, especially as once-isolated people collide. As you move forward, are you exploring a new language to speak of these issues, or are you investigating something new altogether.

Well from a personal position, the thing that I’m doing within my own work is… what is the expression…”physician, heal thy self?” Initially, I am interested in what is happening outside of myself, culturally, but in the end that investigation becomes a mirror for my personal development. If there is a place where I’m hiding, if there are any conditions that I need to focus on, then that’s what I’m invested in. It’s not possible to move forward in any other way. I think the question is still fundamentally the same. When I was working with the animal figures, I was using power animals in order to channel something: to give the images an energy so you can see into the figure, searching for transparency or the soul. There is something mystical about power and the animal, something intuitive and magical.

But this question, for me, requires a visual language. It has to belong to the visual. I really enjoy the freedom of color. I really enjoy the pleasure of play. I enjoy the child-like quality of recovering animal imagery. These are my personal icons and I’m returning to the relationship with myself, able to enjoy something like, “Yes, I’m the ‘Queen of Cats!” It’s a little bit selfish and I’ve often been critical of other work that has been so, but at this moment I feel that it’s maybe ok to do a little bit of that. I’m going to play with light, form, color and something that is not so explicit, not so literal in its expression.

My hope for the future is that we don’t have to belong as much to these segregated labels: just as national identity can afford specificity and community, it can become excessive, dangerous and dark, and I hope that within individual bodies we can have a sense of who we are and still play with a tribe in a gentle way. There is an evolutionary process at work and I can see the potential.