Contemporary art is no stranger to environmental issues, though the question of how artists engage in our ever more pressing crisis of nature is undergoing a fundamental shift. In the wake of the ‘anthropocene’—or ‘the age of man’—a new generation of thought is emerging, which no longer places humanity at the centre but rather re-engages with notions of species interconnectivity, exploring what it might mean to be ‘post-human’.

The Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology (LABAE) describes itself as a ‘multidisciplinary platform for planetary becoming’. Founded by Dea Antonsen and Ida Bencke, LABAE defies categorisation. Neither wholly a curatorial body nor a publishing house, they initiate experimental exhibition formats and work with researchers, writers and artists. Their events kicked off last year with the ‘Transspecies’ assembly in Copenhagen, held in the Dome of Visions, which hosted a series of talks, collaborations, conversations and artworks framed by the drive to establish an ethics of ecological care.

Naja Ankarfeldt: ‘Tale of the Non Human’, 2015 // Courtesy of the LABAE

The Laboratory embraces confusion, celebrating both the shared strategies between artistic and scientific research and the complexities and contradictions that these collaborations often expose. It is a space where anything is possible. I met Ida Bencke, the Laboratory’s co-founder, to unpack some of these ideas.

Rebecca Partridge: Could you tell me something about how the Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology began?

Ida Bencke: The Laboratory grew from a strange mix of deep environmental concern and curiosity towards contemporary attempts within art, literature and philosophy to radically rethink categories formative to our (western) thinking: humans versus animals, nature versus culture, etc. We were never sure whether approaching environmental issues from the perspective of experimental aesthetic practices was the right thing to do, and we are painfully aware of the privileged position we are talking from when attempting to grapple with very real issues, such as global warming, from a philosophical perspective. However, being educated within the fields of art and literature, this felt like the only thing we really knew how to do. Also, we wanted to work from within this fundamental insecurity itself, within a methodological space of doubt, which is why we chose the term ‘laboratory’. Art and literature often make use of the term ‘experimental’, but we wanted to inquire further into this word: what does it mean for aesthetic practices to take on an experimental attitude towards the world? Does that mean they can fail, and how do we identify such failures? This is what Donna Haraway‘s request for philosophy to ‘stay with the trouble’ means to us, and that has been a guiding principle in our work.

Rosemary Lee: ‘Sonic Cannibal’, 2015 // Courtesy of the LABAE

RP: Your own background is in literature and the Laboratory has collaborated with writers, and published books. Linguistic questions appear to be at the heart of what you are doing. Could you say something about that?

IB: Coming from the field of literature in general, and experimental poetics in particular, my thoughts are haunted by problems of representation: these assumed gaps between things and words, language and world, which tend to expand into discontinuities between (talking) humans and (mute) nature. This has been a fundamental trouble within western thinking and the problem of representation has been, and still is, a huge trauma for poetry attempting to engage or somehow include alterity. As Danish poet Inger Christensen puts it in one of her poems: ‘who knows whether the things themselves know that they are called something else?’. Experimental literary practices have begun to approach this problem in radical ways, creating interfaces for communicating with plants, co-writing poetry with bacteria, etc. While many of these experiments are problematic at their core—ultimately translating from a nonhuman semiotics to a human semantics—they still point towards the fact that ‘we’ are not alone in communicating and presenting our senses of the world.

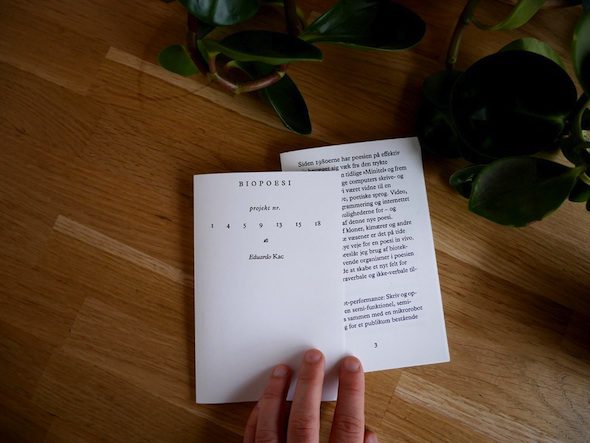

Publication: ‘Biopoesi’ by Eduardo Kac, published by Laboratory for Ecology and Aesthetics

RP: There is a lot of talk about embodied practice currently, as well as practices which blur disciplinary boundaries, both of which could be read as strategies to overcome this ‘problem of representation’. Could you say something about how issues of subject and object connect to ecology and our contemporary understanding of ‘nature’?

IB: I would approach this question from a different angle and say that from my perspective, there are no practices that are not embodied, and that embodied practice in whatever form is what makes the world, what constitutes ‘nature’ in the first place, if we are to hold on to that troubled and troubling term. Feminist philosopher and quantum physician Karen Barad introduces an exciting approach to such questions by insisting on the inseparability between matter and discourse: knowledge-making practices are all part of the world in its intra-active becoming, there are no entities, no identities prior to intra-action. We are all, in other words, becoming with each other. No practice, however ‘scientific’ and ‘objective,’ is able to separate itself from its environment. Knowledge is always situated, partial and directly engaging its ‘object’ of study. From this perspective, it really makes no sense to even distinguish between subject and object any longer, and this is where thinking gets really radical compared to the also very situated Western ontological dogmas through which we usually encounter the world. This recognition, ideally, could be a ground for rethinking ethics from a non-anthropocentric perspective. As Barad so beautifully puts it, it is not so much a matter of taking responsibility for the other, but of response-ability: of making the other able to respond. Making otherness able, I would say, is one of the great challenges and potentials for radical ecological practices.

Tue Greenfort: fungal-workshop // Courtesy of LABAE

RP: This is very exciting. Thinking about this idea of ‘intra-active becoming’, you have recently curated an ‘assembly’ in Copenhagen, which brought together writers, curators and scientists for a program of conversations, exhibitions and interactions. Were you surprised by what emerged from this?

IB: ‘Transspecies’ was an attempt to create a space, however tentative, temporary and flawed, for conversations about planetary interconnectedness. We were guided by Haraway’s question: ‘who do ‘we’ become when species meet’? Our goal was to establish a space of confusion in which we, the curators, ideally would be the most confused participants of all. ‘Transspecies’ was hosted by Dome of Visions, a temporary building and greenhouse situated by the Copenhagen waterfront and experimenting with creating alternative spaces within the city to ponder environmental issues. We called ‘Transspecies’ an assembly, gathering a number of artworks, thinkers and scientists all concerned with issues of trans- or multi-species collectives and identities. The idea was to initiate dialogue between unalike agents and fields of knowledge, and to create a space of curiosity and collaboration between disciplines. The best compliment the event was given was from a member of the audience who described it as an atmosphere of generosity. This was our goal; to create a non-judgmental space for exploring intimacies between species. It felt like, at least for a short period of time, we succeeded.

Lydperformance: ‘Inconsistent Attunements’, Marie Højlund og Morten Riis, 2015 // Courtesy of LABAE

RP: So what is coming up next?

IB: Our next project is a collaboration between the Laboratory, the Danish experimental poet Morten Søndegaard, the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences at Copenhagen University and the Medical Museum in Copenhagen. We’ve been invited to collaborate with medical scientists exploring sugar—one of the truly great evils in our health-concerned culture—as a both endo- and esosomatic substance and agent. That is: as a material working both within and without our bodies. Sugar, we have learned, is not ‘just’ a sweetener, but a fundamental building block of life. Sugar production, of course, plays a central role in the history of colonization and the building of the world economies we know today (as well as a great deal of European Art Institutions). In short, sugar as material turns out to be a quite ‘agential’ material, meaning that it actively does a number of things to ‘us’ that potentially challenges anthropocentric narratives in which humans are the sole actors and makers of history. The goal is to explore the various manners in which science and art know the world, and also the manners in which materiality itself—here, sugar—both troubles and co-operates with such inquiries.

Additional Info

Writer Info

Rebecca Partridge is an artist and writer based in Berlin.