Article by TL Andrews in Berlin // Monday, Aug. 08, 2016

Sholem Krishtalka remembers it vividly. He was waiting for his boyfriend in the lobby of the Kunstraum Kreuzberg exhibition space, where they were planning to visit an audio installation. Spring time had softened the air and the afternoon sun stooped through the arched windows of the 169 year-old building. An Israeli man with just enough stubble on his jaw to be a fragrance model walked through the doors. He noticed Krishtalka and did a cartoon-like double take. “Are you the guy who does the diaries?” The man went on to gush about Krishtalka’s work and how much he could identify with it. Krishtalka blushed; after eight years of art school in Montreal, he had become accustomed to taking critique but he hadn’t quite learned how to take a compliment.

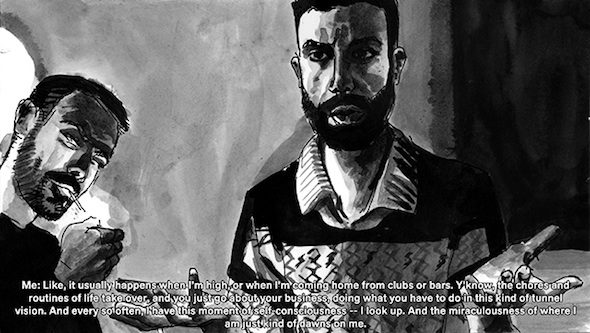

Sholem Krishtalka: ‘Weihnacht’, ink and wash and digital media, 2014 // Courtesy of the artist

That the man could recognize Krishtalka at all is quite remarkable. The diaries are shadowy ink sketches of his experiences in Berlin: non-indexical prints that don’t exactly lend themselves to creating celebrities. But their content is often so raw and vulnerable that people are beginning to identify with something below the surface.

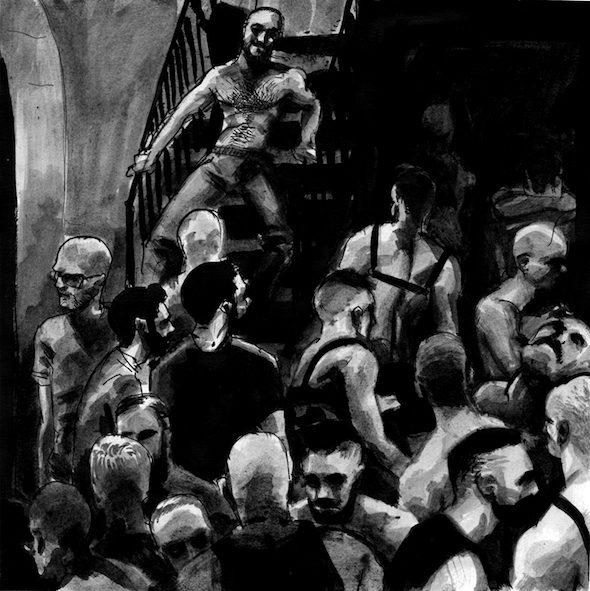

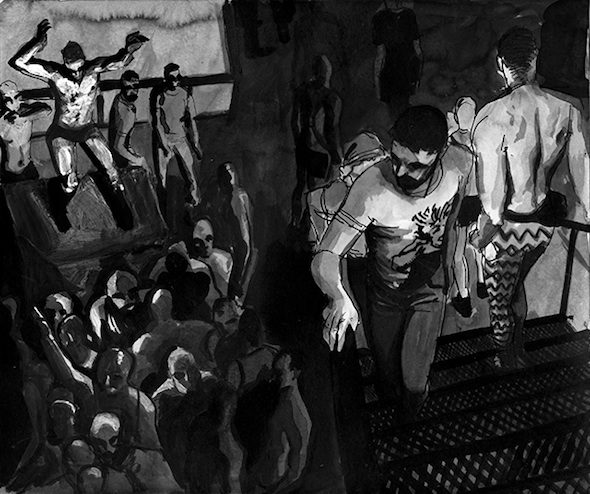

Like any other diaries, they document mundane events such as the search for an apartment or a visit to a clinic, but they also depict deeply intimate encounters with lovers. Not only are they a shrine of experiences that “range from the sad to the traumatic,” as Krishtalka puts it, but they also break boundaries in that they narrativise Berlin’s otherwise superlatively secretive queer scene, creatively breaking the ban on images at Berghain, for example. That is what people are so refreshed to see, that is why they are beginning to stop him on the street. It bothers him a little that some readers draw conclusions about his character from the content. “People think I’m a drugged out whore,” he says with resignation. But it’s a price he happily pays for his artistic archive.

Sholem Krishtalka: ‘Silvester’, ink and wash, 2014 // Courtesy of the artist

Krishtalka has been sketching throughout his entire life. “I’ve always doodled. I was that kid,” he says in his two room apartment that doubles as a studio. The native Canadian fiddles with his ankle as he lifts his bare feet onto the sofa in a scissors posture. “If no one gave a shit I’d still be doing it.” He says he does not track any of the traffic on his tumblr site, or even use analytics to figure out how many unique views he gets: “It’s easier to do this in an assumed vacuum.”

He remembers the scene with the Israeli man so comprehensively because making the diaries has forced him to mentally record everything in cinematic detail. Over the past three years he has turned ephemeral encounters into 47 episodic memoirs of his time in Berlin. He does not use technical recording devices, “I am a camera,” he says, quoting English writer, Christopher Isherwood, one of his influences. Isherwood famously wrote a book called ‘Goodbye to Berlin’ about his time in the German capital too. Krishtalka also lists Nan Goldin’s candid portraiture of the LGBT community in New York as another big influence.

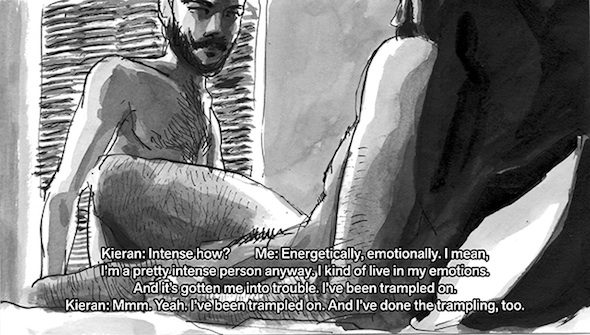

Sholem Krishtalka: ‘Boys of Summer (Kieran)’, ink and wash and digital media, 2015 // Courtesy of the artist

Krishtalka is very aware of the unreliability of memory as a documentary tool, which is why he asks his characters to corroborate and approve the sketches before he publishes. “I have a commitment to honesty,” he says, “as distinct from truth.” He is more interested in an account that does not distort, omit or subvert information rather than 100% fidelity to facts. Most characters affirm his accounts; if they don’t, he won’t publish. Still, it could be argued that his recollections do fictionalise events in the same way that all memory is a fiction of real occurrences, a faint mist on a choppy ocean of history. “It’s funny, the things I get wrong,” he says through a smile. Thinking back on older sketches he winces at how his memory invented windows where there were none before. The emotions, however, those are rock solid.

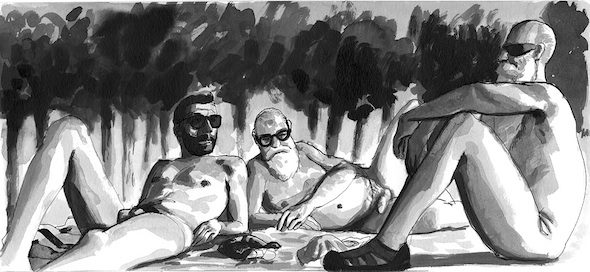

Sholem Krishtalka: ‘FKK’, ink and wash on paper, 2013 // Courtesy of the artist

Krishtalka is not comfortable associating his work exclusively with the gay scene, he prefers the term queer. “Gay art refers only to sexuality. Queer implies there is more to consider.” He also prefers queer because he sees homosexuality as a term defined in opposition to heterosexuality; queer is more self-sufficient.

He does not attempt to explain any of the events in his narratives, which he sees as a political decision. By treating the events with the same unqualified matter-of-factness that a straight white man might apply to heteronormative texts, Krishtalka asserts his self-evident right to be. And as he does that, he gives readers the permission to do the same.

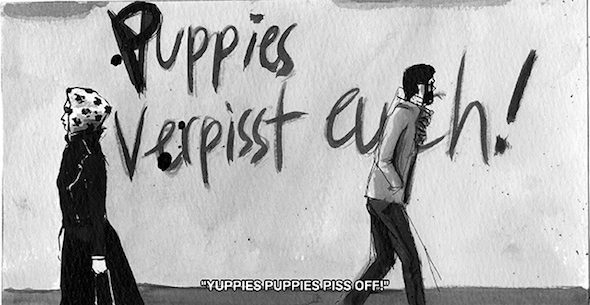

Sholem Krishtalka: ‘Flat’, ink and wash on paper and digital media, 2013 // Courtesy of the artist

Artist Info

Writer Info

TL Andrews is a multi-media journalist based in Berlin. He produces features for radio, television and print outlets with a focus on Berlin, Germany and European themes.