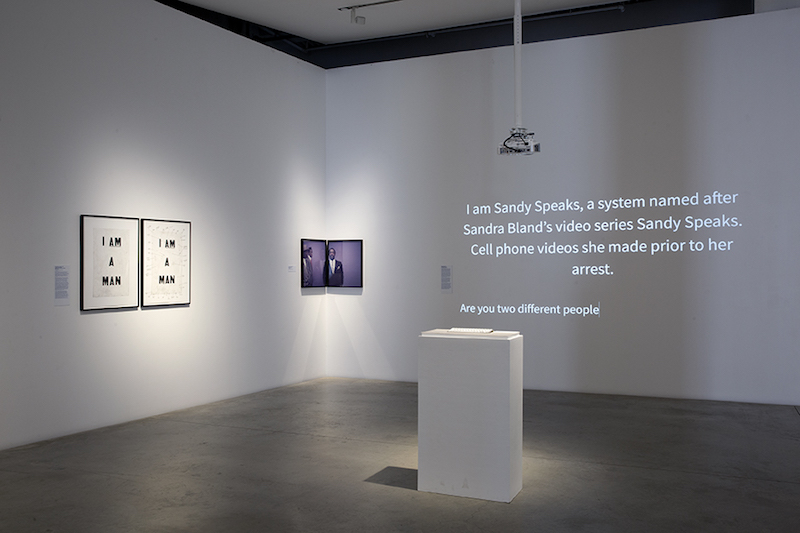

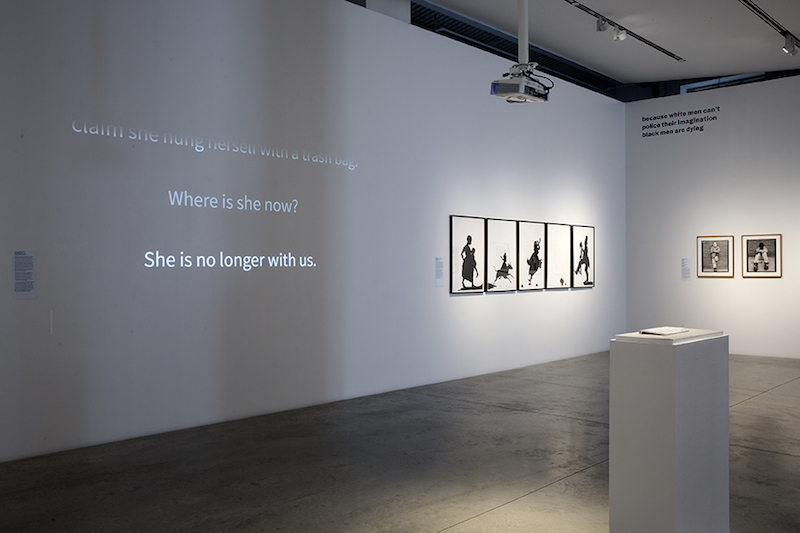

In 2015, a 28-year-old black woman named Sandra Bland was arrested after being pulled over for making an illegal lane change. Three days later, she was found dead in her Texas jail cell. This story, as well as her own video project ‘#SandySpeaks’, have since been distributed widely on social media platforms. In a recent project, also named ‘Sandy Speaks’, New York-based interdisciplinary artist American Artist created a chatbot to whom users can ask questions about police brutality and the prison surveillance system in America.

American Artist: ‘Sandy Speaks’, 2017, AI chat platform, installation view at Memory is a Tough Place // Courtesy of the artist and Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Gallery, NY, Photo by Marc Brems Tatti

I’ve been familiar with American Artist’s work for a few years, and have been consistently moved by the thoughtfulness with which they tackle topics around activism and race. American Artist’s legal name change acts as the basis of their practice. It insists on the visibility of Blackness as descriptive of an American artist while maintaining an anonymity in virtual spaces. In this interview, we spoke about the complicated relationships we have with technology today. In January, American Artist’s solo show ‘Black Gooey Universe’ opens at HOUSING in Brooklyn.

Ilyn Wong: I want to ask you about ‘Sandy Speaks’, a work for which you’ve created a chatbot named after Sandra Bland. As its creator, do you think about the bot as having a name, or, for lack of a better word, a personhood?

American Artist: I do refer to the bot as Sandy, and though this does give it personhood, I like to delineate between Sandra the person and Sandy the bot. It’s not my intention to say that technology such as this could recreate or recapacitate a person. I created Sandy as an agent to continue the conversation that Sandra had started, but also to capture the warmth and care that Sandra had when she spoke about these issues: her social media presence by the name Sandy Speaks where she talked about police violence towards Black people.

IW: Beyond how astutely the work tackles problems around surveillance, information, and power, there’s something heartbreaking about ‘Sandy Speaks’. I don’t usually think about information and its distribution as intrinsically having emotional weight. But, of course, it does. How do you see the role of information—including the bot’s formulation and distribution—as gestures of political subversion?

AA: I don’t think most users our age see data or its technologies as having emotional weight, or as capable of signifying much of the violence that’s embedded in them. It attests to the success of those creating technology that they’ve been able to promote an image of lightness, and transparency, which is simply not true.

In ‘Sandy Speaks’ the most obvious violence aside from Sandra’s case itself is the violence of bureaucracy. The chatbot as a device is often used to alienate people from the services they need, public and state services, for example. But I wanted to reframe that by offering people useful information to survive encounters with the police and to learn more about Sandra. If you might have a run in with the police, and saying the wrong thing could get you killed, that knowledge is vital.

American Artist: ‘Sandy Speaks’, 2017, AI chat platform, installation view at Memory is a Tough Place // Courtesy of the artist and Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Gallery, NY, Photo by Marc Brems Tatti

IW: I think what you’re saying is why I find this work emotionally jarring. There are a lot of complicated layers around technology, social media, and self-representation, which somehow relate to the way this very technology oppresses us and obscures a lot of pain. The questions I’ve been wanting to ask Sandy are in the vein of, ”how did this happen?” which is also “how does this continue to happen?” She, on the other hand, communicates in a sort of tidily packaged way, making it simultaneously a relief and frustration. What are your thoughts?

AA: I think having to read these events through text leaves space for people to feel the weight that they bring. In the media we are bombarded with viral imagery of Black death and it becomes a novelty, something to trade or exhibit in your feed before anyone else does. I’m interested in escaping that loop of visual consumption in order to engage in a deeper way. It was important for me to not show Sandra or to rely on her image in the work because I didn’t want to reinforce that cycle.

It is true that people want to ask Sandy the real existential questions. I’m not sure if it comes from a thought of, “this is the first non-bureaucratic bot I’ve ever talked to, maybe it will answer the tough questions!” or merely not understanding how a low-level AI works [laughs]. I don’t blame people for wanting an answer to why things are the way they are, but that’s not the type of answer you can give objectively. I think my favorite question someone has asked Sandy so far is: “What do we do after the prison system is abolished?”

IW: I typed in that question, and her response was, “What?” Maybe this is the failure of a low-level AI, but I chuckled when she said that. Maybe that’s telling.

AA: Actually, Sandy should have an answer for that: “We will write our own history books.”

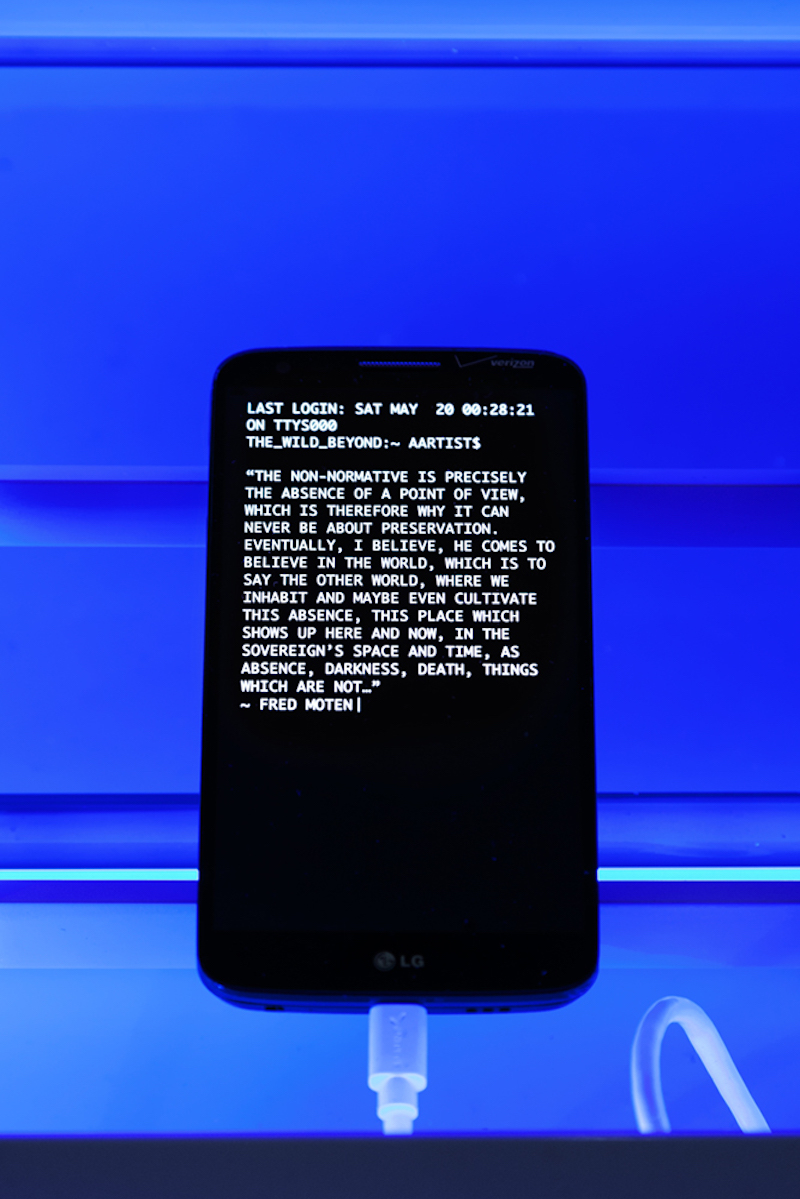

IW: Let’s talk about another work called ‘The Black Critique (Towards the Wild Beyond)’. I recently saw this work at The Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts in New York. The installation, which consists of a large metal case set atop trestles, emits this otherworldly blue light. Inside the case are different cellphones that type out quotes in white letters on black screens into a command-line. As the viewers read these lines of text, we realize that the quotes don’t actually successfully signify meaning as command lines, thus failing the function of the machine. Where is the moment of meaning-making in these equations when mechanical or automatic responses don’t amount to a codified direction?

AA: ‘The Black Critique’ is a mechanism for converting smartphones to a black interface. It’s an abstract machine. The large metal locker contains germicidal UV lights, and is based on a device that exists commercially to cleanse hardware, such as smartphones or laptops. I wanted to take it further and say that the machine could do something impossible, it could erase the white interface embedded in the screen.

Inside the locker are various models of smartphones, all displaying command-line on a black backdrop. One-by-one, quotes from different authors are typed into the command-line, quotes that speculate on blackness as an outside to power as such, but as something habitable. The technological devices we use are primarily designed and developed by white men, but they are tools for everyone’s everyday use. How might we consider Saidiya Hartman’s notion of “the hold” (of the slave ship) in the context of this relationship? And for Fred Moten, what does a fantasy within the hold look like?

The recognition of the quotes as malformed commands is indicative of a lack. In one sense, it signifies the impossibility of merely converting a white power structure into something hospitable to a Black user. In a more literal sense it conveys the inability for thought and emotion that doesn’t register as a command to be mobilized in an economy that only values innovation and efficiency.

American Artist: ‘The Black Critique (Towards the Wild Beyond)’, 2017, Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts, NY // Photo: Martha Fleming-Ives

IW: I’ve come to think of my smartphone as not just a mode of communication but maybe also sustenance, something like an organ (we can’t live without), but yet so quickly replaced by the next (better) model. I’m curious about the smartphones in ‘The Black Critique’.

AA: The smartphone is important because it represents the culmination of so many things. It’s essentially a computer, though somewhere down the line it was presented as a phone. I blame Apple for this because before the iPhone there were PDAs if you remember: Personal Digital Assistants or handheld PCs. The semantics changed, but the technology is the same. And I think that a computer with internet is the bare minimum of what’s necessary to access or distribute all information, potentially. So in that, minus ISPs and phone carriers and all that shit, there’s not much of a limit to what one person can do with a smartphone.

American Artist: ‘The Black Critique (Towards the Wild Beyond)’, 2017, Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts, NY // Photo: Martha Fleming-Ives

On the flipside, the phone is how you are surveyed: all of your personal information is in it, and it ultimately becomes a representation or a stand-in for you. If everyone has a smartphone and each phone has all the information on that person, each phone becomes a body double for a person, in a way. The analogy there is not lost on me, and in some way these phones in this work connote individual bodies.

But as much stake as I put into the smartphone as an image, I know it is a very temporary structure. It is just the current form for something that’s been developing for a long time and will continue to develop. In a few years, we won’t have them.

Artist Info

HOUSING

American Artist: ‘Black Gooey Universe’

Exhibition: Jan. 26 – Feb. 16, 2018

424 Gates Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11216, click here for map