Article by Zoe Cooper in Berlin // Thursday, Mar. 8, 2018

The first thing you do when you visit the Embassy of Canada in Berlin—or any embassy, for that matter—is go through a security checkpoint. Once your body and belongings have been thoroughly examined, you continue on to the next room, the Marshall McLuhan Salon, a rotunda filled with an immersive installation by Canadian artist duo Bambitchell (Sharlene Bamboat and Alexis Mitchell). Multi-colored lights turn on and off as if in conversation with one another, accompanied by dialogue on a soundtrack and multiple videos.

Bambitchell: ‘Special Works School’, 2018, installation view at Marshall McLuhan Salon // Photo by Corrina Mehl

Part of the 2018 Berlinale’s ‘Forum Expanded’ exhibition and titled ‘Special Works School’, the piece takes its name from a group of artists employed by the British War Office from 1917 until 1919 to work as “camoufleurs,” people responsible for developing camouflage technology used by the military. The army employed visually astute creatives—painters, textile artists, scenographers, designers, sculptors, you name it—to render the visible invisible. Bambitchell’s immersive work implicates various senses, such as sight, hearing and smell, to encourage viewers to reflect on how it feels to be surveilled. The artists ask us to consider: what are the psychological implications of being surveilled? How does it feel to be the surveiller? In what ways do we surveil ourselves?

Berlin Art Link sat down with the artists to talk about the role of the artist in the military, the process of making an immersive installation, and what it means to show contemporary art inside an embassy.

Bambitchell: ‘Special Works School’, 2018, installation view at Marshall McLuhan Salon // Photo by Corrina Mehl

Zoe Cooper: How did your interest in surveillance and the military come about?

Alexis Mitchell: We read this book called ‘Hide and Seek’ by Hannah Rose Shell, which a book about the history of camouflage, and that’s specifically where the reference to the Special Works School came from.

Sharlene Bamboat: I think one of the more common things people know about are these things called “dazzleships.” Around the same time period, painters were also hired to paint these military ships. They’d paint these weird stripes and color them in different ways, so that torpedo couldn’t tell the difference between where the water ends and the sky begins and ship begins. The ships just look like these patterned things floating on the sea. We had talked about that at one point, because we wanted to add to conversation in a different way, but it is really nice to think about all the colors and patterns—it’s actually really fabulous! They look like dresses on the sea or something.

ZC: The installation doesn’t just focus on the aesthetics of the Special Works School but also the sounds. The soundtrack is an integral part of creating the kind of theatrical environment you’ve made. How did the sound piece come about?

AM: We’re starting to look at aesthetics in a broader way, in terms of sensory perception, how we perceive, and specifically how we perceive surveillance or camouflage. We wanted to get back to a more holistic or sensory feeling about what surveillance might feel like. In order to do that, we started to think about senses like smell, touch and taste. The script moves through each one of those senses, but very early on we knew we wanted the sound to be quite intense, because often we think about surveillance as a very visual medium yet it is very much also about sound and scent.

So we started working with Richy Carey, a composer who had done a lot of research on color and sound. It became very important for us in terms of thinking about aesthetics and surveillance and how color functions. We sent him the written script really early on and instead of creating a visual language for the film, we wrote the script and worked specifically with him to develop the sound before we did any of the images. We weren’t sure what the visuals were going to be—that’s how much we wanted the sound to take precedence.

SB: With the sound, each of the characters has a different frequency and background noise, some of which is audible, some of which is not, and only to some people. For example, purple, which is the voice of a god character in the film has a lower frequency called a “ghost frequency,” which is meant to create anxiety. They often use this frequency in horror films to make people feel creeped out. There are these subtleties of purple as the voice of god, such as it also being a regal color.

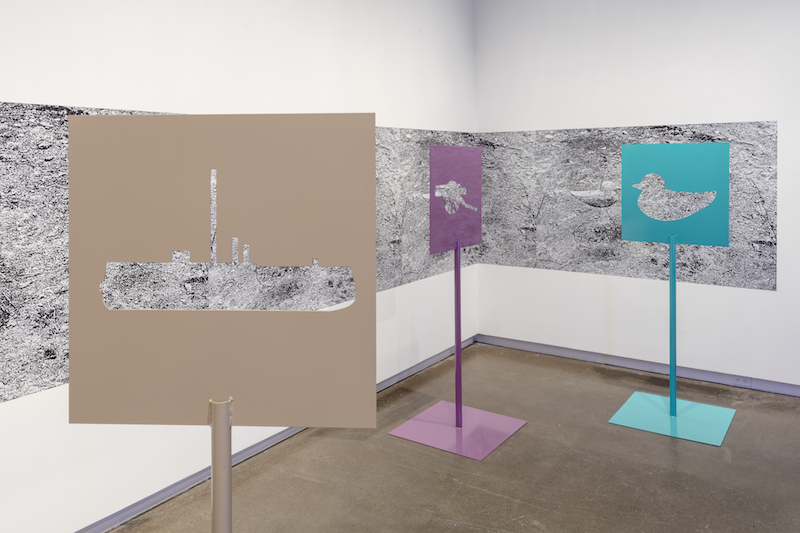

Installation view of ‘Special Works School’, 2018, installation view at Gallery TPW // Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid

ZC: What do you feel like this project might reveal about the relationship between politics or military action and art, specifically taking the location into account?

AM: I’m happy that it’s in the embassy. Often when you think about work in galleries it feels self-congratulatory or a pat on the back. I think, to both of us, art sometimes feels futile in a way that it’s hard to get.

SB: Galleries attract the same people all the time, so new perspectives don’t get brought in. Whereas in a space like this, in theory, people who would not just go to a regular gallery space can walk in and say “Oh, what’s this? Maybe this piece interests me.”

AM: Also having it in this space names what it means to be making art in this moment in time. We can supplement so many institutions for each other, you know? So many galleries are funded by governments and companies, and the logics of globalization and capitalism are quite inescapable. Somehow having it in this space like it’s just there…

SB: It just lays bare. There’s nothing to pretend. One thing we wanted to tease out is not just how surveillance is felt on the bodies of those who are surveilled, but what happens to the people do the surveilling themselves, because we all surveill ourselves all the time now. The most obvious example is social media, but we didn’t want to go down that road. Our character Sand is the surveiller, but at the film progresses, all of Sand’s senses disintegrate. What happens to our subjectivity when we’re watching and consuming and becoming other things constantly? There’s a phrase in the film, “camoflauge consciousness,” which means in order to blend in with your background, as one does with camouflage, you don’t have to blend in with the tree; you have to become the tree. So what happens to you when you have to become your background? Where does foreground and background end, where do you end and begin? That’s something we wanted to tease out. Sand’s voice in the film starts kind of straight up, and then it disintegrates and you just hear choppy electronic stuff.

Installation view of ‘Special Works School’, 2018, installation view at Gallery TPW // Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid

ZC: We’re so used to talking about art as a form of political protest. This almost shows the opposite, that artists can be on the government’s side too.

AM: Yes. It was important for us to show this has always been the case. The line between artist and citizen, or artist and government, it’s always blurred.

Bambitchell: ‘Special Works School’, 2018, installation view at Marshall McLuhan Salon // Photo by Corrina Mehl

ZC: People often incorrectly assume that artists are always on the side of the resistance to government action, and that’s not necessarily true. Artists are people and people don’t necessarily think all the same way.

AM: And there’s a certain level of experimentation that happens within artistic practice that gets co-opted by lots of things in many ways.

SB: By all powers! We were trying to show this area is way more grey, that nothing is black and white in this situation, and it hasn’t been. The Special Works School was around 100 years ago, during the First World War.

AM: And now we’re in the Canadian Embassy, being “the proud Canadian artists” supporting our nation.

SB: Or technically, our nation supporting us. Back and forth.

ZC: It’s less cut and dry than many think.

SB: And people want it to be cut and dry, because it’s easier to think that way.