Interview by Lucia Longhi // May 06, 2019

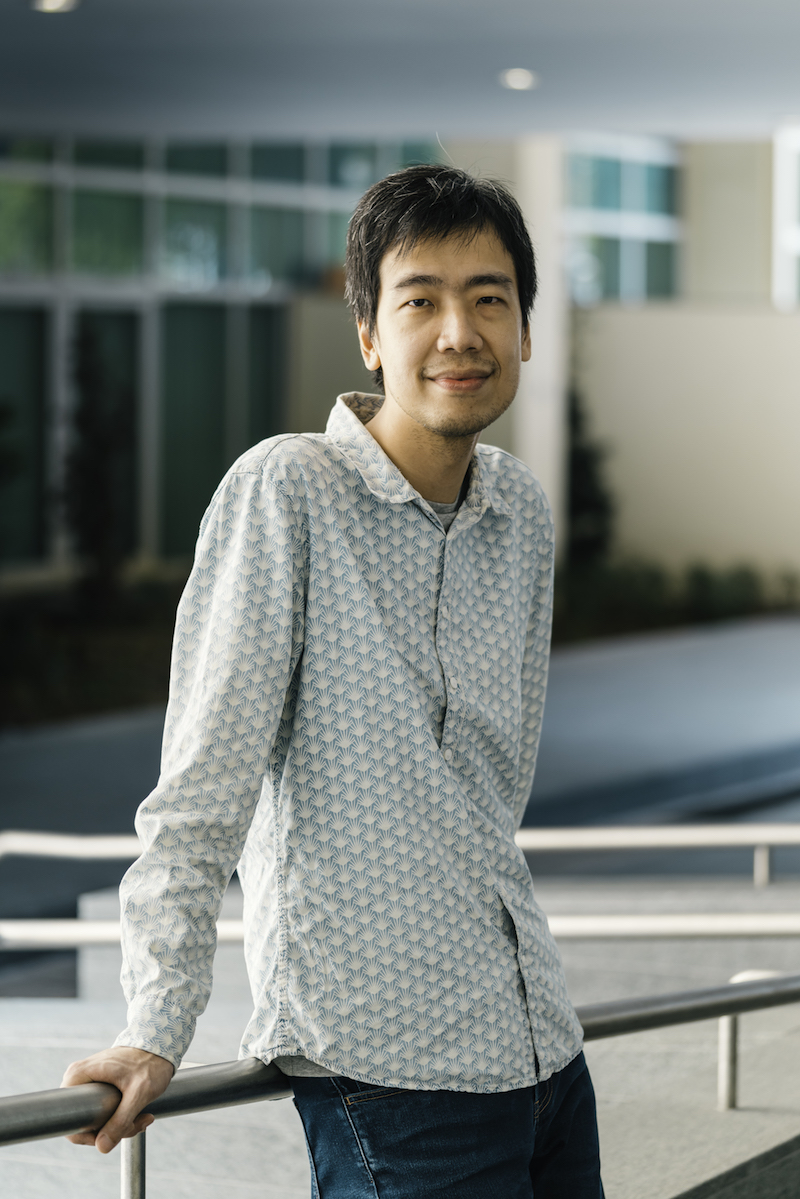

Singapore-born and Berlin-based artist Song-Ming Ang uses sound as a malleable material, producing artworks that ultimately embody the manifold ways we experience it. Music is the product of both manifest and hidden issues: a combination of—sometimes preordained, sometimes improvised—codes, conventions, rules, paradigms, expectations. Song-Ming Ang creates objects, videos and images that reflect on our multifaceted relationship to music, both as individuals and as a society.

Going through processes that are often complex, including archive research and audience participation, the artist undertakes an inward inspection of different subjects relating to the realm of music: instruments and objects, iconographies, traditions, attitudes, musical taste, personal life stories. He examines their formal and conceptual complexity, the layered accumulation of significances they contain, and then give them back to us under a different, often slightly witty perspective. His method often requires time and patience. He has, for example, disassembled and then perfectly reassembled a piano (‘Parts and Labour’, 2012); he repeatedly reproduced Justin Bieber’s signature until achieving its perfect imitation (‘Justin’, 2012); he played a famous Bach composition in reverse (‘Backwards Bach’, 2013); he asked former students to remember their school songs (‘Be true to your school’, 2010); he invented new music genre names from the future, and their related graphics (‘Postcards from the future’, 2018); and he is now creating a collective song which could change the world (‘A song to change the World’, 2018–).

Song-Ming Ang: ‘Parts and Labour,’ 2012, deconstructed piano and HD video, 26 mins // Courtesy of the artist

The final results of his practice are frequently rather minimal products, reduced to their essence. The artist does not add aesthetic or formal layers, but rather plays and reasons on the existing ones, exploring from within. He thus remains faithful to the object of departure, but at the same time questions its essence and the social role or perception attached to it by conventions and habits.

Song-Ming Ang will represent Singapore at the 58th Venice Biennale this year with a project that takes the musical tradition of his country as a starting point for a further development of his research on music as a collective and social medium.

Song-Ming Ang at the Singapore Conference Hall // Photo courtesy of Dylon Goh for National Arts Council Singapore

Lucia Longhi: Your artistic path started as an experimental musician and from that experience you started questioning some crucial subjects: the issue of originality in music; the definition of music genres; music as a collective creation rather than an individual expression; the contexts in which society undergoes music. How did you experience these issues in your routine as a musician? And how has the realm of visual arts allowed you to explore these topics in a different way?

Song-Ming Ang: As a musician, I was mostly interested in breaking down boundaries and synthesizing genres, to create something that I feel is original, at least to me. At some point, I started making works that weren’t exactly music but were about music, instead. So instead of recording music or playing concerts, I was working with weirder formats like live installations (‘Piece for 350 Onomatopoeic Molecules’) and listening parties (‘Guilty Pleasures’). It was all very organic – they just happened, and the works started to find an audience in contemporary art, which I feel is more open and accepting in terms of what’s allowed. In contemporary art, I think you can do pretty much what you want and it can legitimately be considered art. I enjoy this freedom of being able to work across disciplines, genres, material and media. And in terms of the scholarship, I feel that contemporary art, due to how it has absorbed critical theory, is more equipped to deal with certain methodologies that I work with, such as intertextuality or public participation. But the realm of music retains many charms – I still enjoy going to concerts a lot, for example, and remain fascinated by how fans generate their own forms of knowledge and expertise.

LL: You often investigate how habits related to sound shape our understanding of it. From a substantial point of view, for instance, you sometimes disclose the way sound gets stuck in our head and in our lives in various forms – the persistent visual or acoustic presence of certain musical iconographies. (I’m thinking of ‘Justin’ or ‘Be true to your school’). In your work we can see an attempt to inspect and then overturn these conventions, by subverting conventional codes and training our mind to un-learn them. Do you think a similar process of un-learning is necessary in order to re-learn a new approach to music and sound?

SMA: Yes, a lot of what I do involves trying to understand something by examining it in unusual ways. When I made ‘Parts and Labour’, I was aware that many people grow up with a piano at home, but despite having played it, they would never have had the experience of literally going into the instrument and interacting with it in a physical way. That’s why I apprenticed with a piano workshop and documented the entire process of refurbishing a disused piano. And with ‘Backwards Bach’, I knew that many people would recognize the Prelude but to hear it played backwards would be an uncanny experience, so that’s why I went ahead and learned how to play it backwards. I think unlearning is indeed an important part of learning – to challenge our existing ideas of how things are supposed to be. Fundamentally, it’s about being open to reconsidering my own perspectives. As an artist, I also feel that my main responsibility towards my audience is to offer them other ways of seeing, hearing and understanding things, so it’s something I enjoy doing.

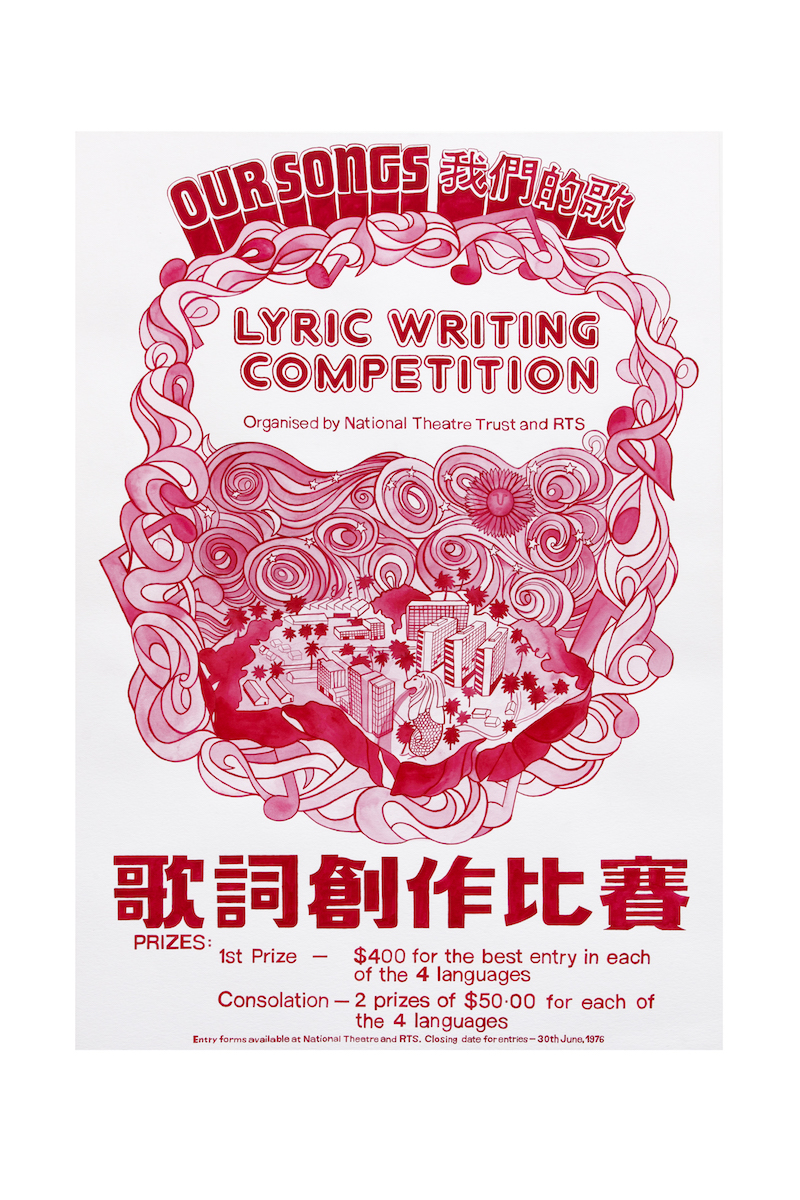

Song-Ming Ang: ‘Our Songs,’ 2019, watercolour on paper // Courtesy of the artist, photo by Mizuki Kin

LL: You seem to have a neat methodological approach: you stay true to the inner quality of the subject you are working with (whether it’s a musical instrument, paper scores or music itself) and the process you undertake is often long and layered, involving other people or even the public. When experimenting with a new project, do you seek a preordained final aesthetic result, or do you rather accept the unexpected? How do you perceive your role in your work?

SMA: As an artist, I do actively switch between various roles, like you point out. Sometimes I’m directing or orchestrating things, sometimes I work from the position of a fan or amateur, and sometimes I feel like a translator between different disciplines. Wearing different hats allows me to try out various ways of working and to discover new things. And sometimes I’m just a conduit or catalyst for things to happen. I try to do just enough to let the artworks make themselves, if that makes sense. With regards to outcomes, I usually have some idea about how things will work out, but it’s also about leaving enough space in the work to allow for productive accidents to happen. I try to make the best out of each situation, to find the right entry point into something, but also to avoid overwhelming my subject. Like you said, it’s about staying true to the inner qualities of the subject I’m working with.

LL: Two aspects seem crucial in your working method: the archive work and the focus on the process rather than the final result. Is this a way to keep your work open, as a sort of non-finito work, and in continuous communication with the public? Could you expand on this in relation to the Biennale works?

SMA: In a way, I do see the world around me as a big archive to sample from, particularly all phenomena relating to sound and music. That’s what I’ve built my entire art practice on, and it’s something that feels endless, since there’s just so much out there for me to look at – not just music itself but its histories across different times and continents, the people who produce and consume it, and the industry and invisible structures that surround it. I think what’s important is to keep finding new ways and processes and to keep things exciting and challenging for myself.

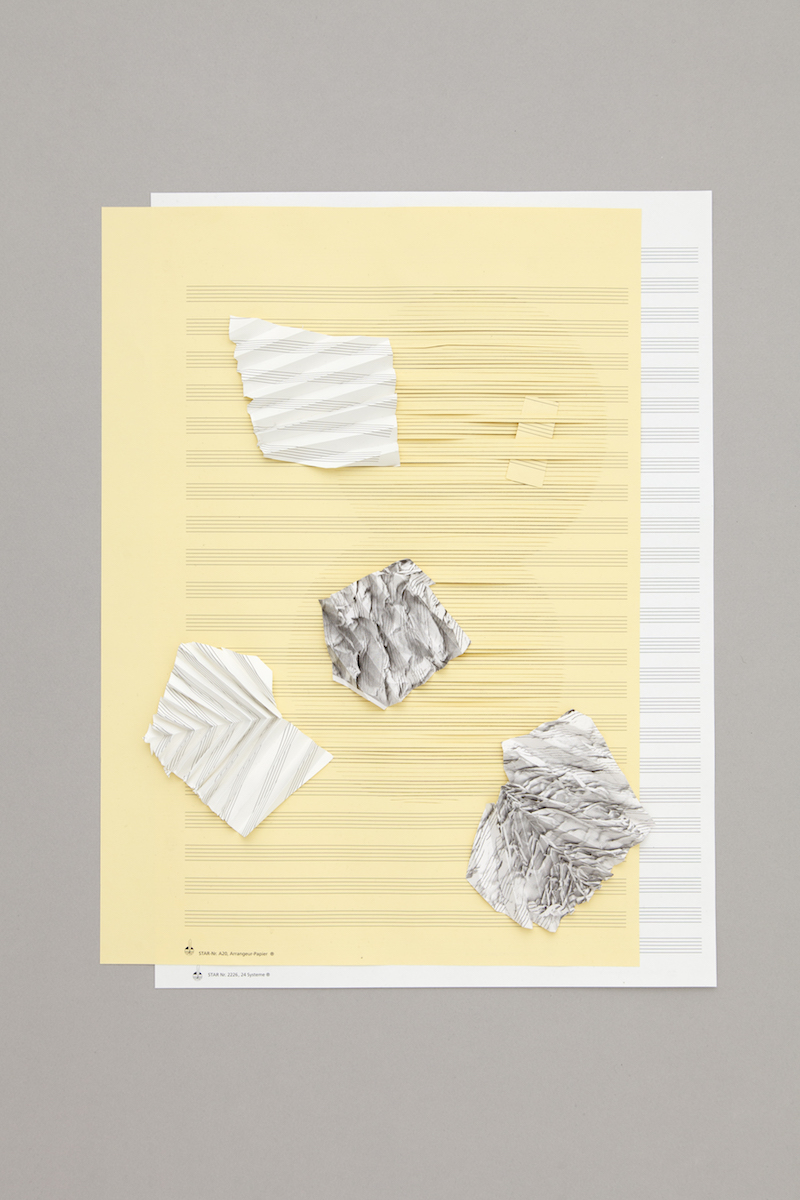

With regards to the works I’m showing at the Venice Biennale, I’d say they were all really fun to make. We’ve got big and colourful banners and watercolours, as well as a film, sculptures and collages that bear the mark of experimentation and play. Some of these works feel like they could go on forever because of how we’re just playing around with permutations, to try to find yet another way of stacking recorders or folding manuscript paper. So there is a sense of openness that comes with the process, definitely.

Song-Ming Ang: ‘Music Manuscripts,’ 2019, mixed techniques on paper // Courtesy of the artist, photo by Mizuki Kin

LL: The main work you are presenting at the Biennale, ‘Recorder Rewrite’, is a video focusing on the use of the recorder in Singapore’s music education since the 1970s. You dig in the tradition of Singapore culture, at the same time indicating that often there are no clear boundaries in the definition of cultural features. The recorder, for instance, could be seen as a melting pot symbol, an original Europe-born instrument that became Singapore’s national instrument. How did this instrument become a clue to explore the story of your country? What is the ultimate intention of your video work?

SMA: In Singapore, we inherited the recorder as part of our music education due to the legacy of British colonialism. However, the instrument actually found its way into many non-European countries, like Japan and the United States. The recorder regained popularity in the 20th century as it was seen by educators as a suitable instrument for children: it’s portable, affordable, sturdy and you don’t have to tune it. But if we look beyond the instrument’s history, what we see is that many people around the world actually share a common experience through it. This is basically the motivation of the film – to evoke an experience that is known to many of us, but at the same time create a feeling that feels foreign. Ideally, the audience should walk away feeling excited, thinking “ah, I didn’t know you could do that with the recorder!” It’s an instrument that can be quite divisive because not all of us who learnt it actually enjoyed learning it. But, as I mentioned earlier, it’s about finding the right entry point and offering an alternative perspective for my audience so that they can understand the instrument in a new way.

With all the artworks, my motivation is to think about what it means to make “music for everyone” – how to be inclusive and open. I think that any person or organization in a position to think about this question is already in a position of power or privilege, to decide what ‘music’ is and who ‘everyone’ is. I hope that the spirit of the artworks reflect this awareness.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

VENICE BIENNALE – SINGAPORE PAVILION

Song-Ming Ang: ‘Music for Everyone: Variations on a Theme’

Exhibition: May 11–Nov. 24, 2019

Opening Reception: Thurs. May 9, 2019

Arsenale, Campo della Tana 2169/F, 30122 Venice, Italy, click here for map

Song-Ming Ang: ‘Recorder Rewrite,’ 2019, film still // Courtesy of the artist