by Dagmara Genda // Mar. 9, 2021

A ritual highlights a given social practice and renders it symbolic on another, often spiritual, level, thereby legitimizing and expanding certain structures or, at other times, rendering them powerless. For Michel Foucault, “rituals of punishment” legitimized and normalized the discipline of the “deviant” body, but in other contexts, like in indigenous resistance to colonial power, rituals can be healing and a source of community. Though art—due to its symbolism, affective qualities, its contemporary designation as a “practice,” among other things—can be compared to ritual, it also has the unique ability to be an individuating activity, one that questions the roles and symbols assumed through ritualistic processes. Rituals of sex or death, for example, can be subverted in art to allow for an experience that falls outside the limitations of social practice.

What could such an experience look like? This is the question that came to mind when I visited Julia Stoschek Collection’s latest show, ‘A Fire In My Belly,’ co-curated by Stoschek and Lisa Long. At the risk of navel-gazing, I will examine the show through the specificity of my experience, in the hope of glimpsing behind the ritual. Specificity is paramount for me because it is the prevalence of the body that stood out in the expansive 37-artist exhibition, whose theme of violence was presented as an existential condition rather than a problem to be solved. This body, however, was not The Body as context or theme, but each flesh and blood body, ecstatic body, pained body, loved body, unknown body, even my body (not “the viewer’s” but mine) as it moved through the show, confronted and was reflected in the art. I found myself embodying the intersections between my gender, sex, vulnerability, power, skin color, size and mortality, though this list could go on.

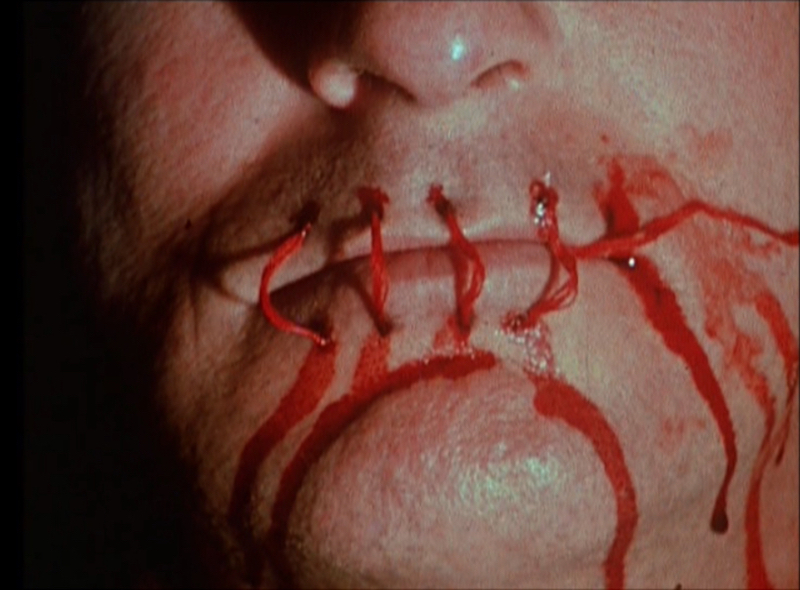

David Wojnarowicz: ‘A Fire In My Belly’ (Film In Progress) and ‘A Fire In My Belly’ (Excerpt), 1986–1987, Super-8-Film transferred to video, 13′06′′ & 7′, Color & S/W, no sound. Video still // Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and PPOW Gallery, New York

David Wojnarowicz: ‘A Fire In My Belly’ (Film In Progress) and ‘A Fire In My Belly’ (Excerpt), 1986–1987, Super-8-Film transferred to video, 13′06′′ & 7′, Color & B/W, no sound. Video still // Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz and PPOW Gallery, New York

The show’s title stems from David Wojnarowicz’s film-in-progress, ‘A Fire In My Belly’ (1986-87), which is one of the first works that visitors encounter. Featured are images of mutilated bodies: legless beggars hobbling across Mexican streets, a bloodied hand catching coins, Wojnarowicz himself sewing his lips shut with red string, the crucified figure of Jesus swarmed by fire ants, to name a few. For the artist, fire ants represented the aggressive machinations of human society, a society that instrumentalizes spirituality and fixes an external, often monetary, value on things so as to enforce its unquestioned norms. Wojnarowicz called these norms the “pre-invented world,” and they are secured by the scapegoating of deviation, of which the artist was a lifelong champion. He sought to undo the mainstream rituals of sex and gender in order to, as he put it in ‘Postcards for America: X Rays from Hell,’ make “room in the environment for my existence.”

Although, in the pre-invented world, my body does not bear the stigma of deviance, I am made aware of how, given the right conditions, it might. In Rindon Johnson’s ‘It is April (JSC)’ (2019), a television-set sits at just slightly below my eye level on a plinth. It features the back of a black man’s head, approximately life-size. I watch as a woman’s white hands slowly slide up to his face. They blindly feel their way across his cheeks, head, neck. He is not wearing a shirt. The effect is sensuous, often erotic, but sometimes investigative and harassing. I do not feel like a voyeur. I am not staring through a peephole but standing in close proximity behind a shirtless man. He would certainly be aware of my presence, if he were actually here facing the wall. The white hands, so similar to mine, continue to grasp at his face and I, all but breathing down his neck behind him, can’t help but think he is surrounded. I’m not sure I’ve ever perceived myself as a potential threat, but today images of violence against black men are common currency. One need only go two floors higher, where Arthur Jafa’s frenetic mash-up of black ecstasy and death strobes in an empty theatre. Then again, Johnson’s piece is also tender. The suggestion of aggression is followed by a touch of trusting intimacy. I can almost smell the scent of his scalp, an aroma that can be an aphrodisiac for lovers and a signal of trespassed boundaries between strangers. At the end of the piece, when he bends down, it’s not clear if the insistent hands pull or if he eagerly yields. Love’s rituals are supposed to bridge difference, but what barbs are placed in its path? What does systemic racism do to real relationships?

Rindon Johnson: ‘It Is April (JSC),’ 2019, HD video, 12’02’’, color, no sound, video still // Courtesy of the artist

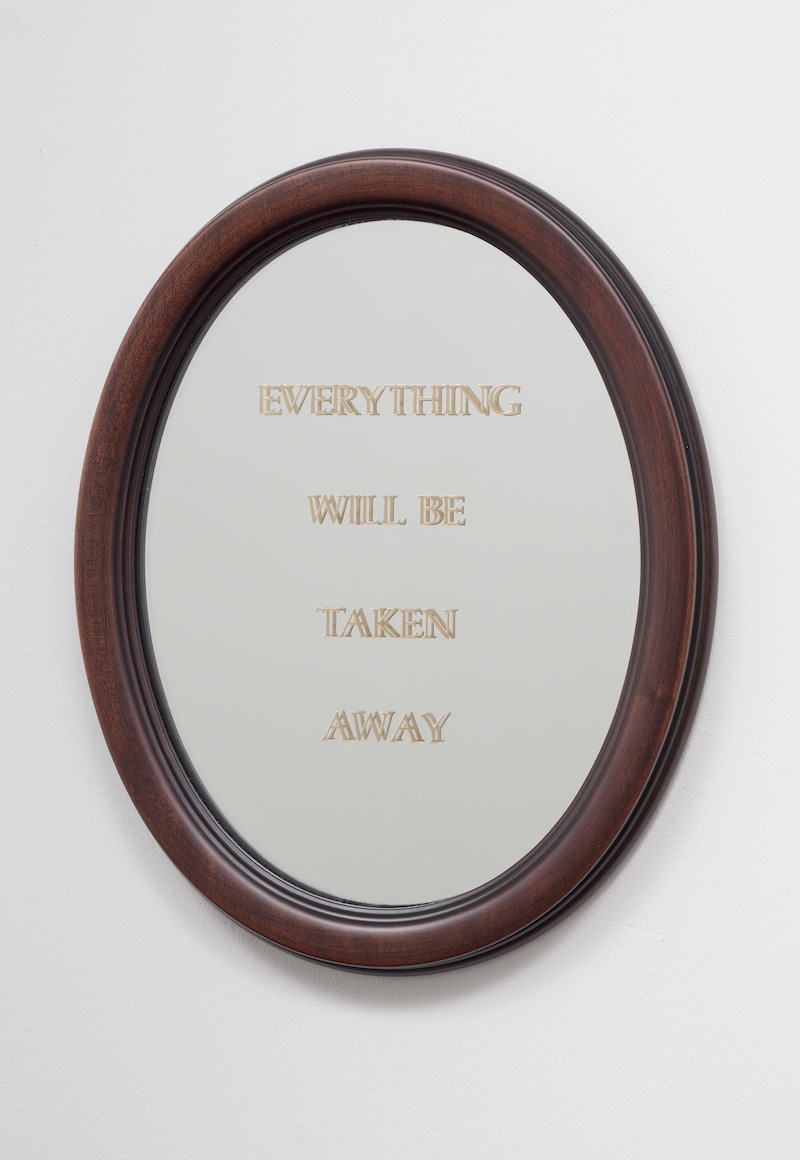

A work that evokes a similar bodily quality, though in a very different way, is Adrian Piper’s ‘Everything #4’ (2004). Though it is a small oval mirror hanging on a wall, it parallels Johnson’s work in that a central part of the piece is a head, this time my own. On the mirror’s surface the phrase “Everything will be taken away” has been engraved and highlighted with gold leaf. A spotlight illuminates the work, causing it to cast an oval light, with the words shadowed in reverse, on the floor. Though I usually find the use of mirrors in art a distracting seduction—the obvious enjoyment of an audience looking at its own reflection strikes me as obscenely exhibitionistic—this time it is different. My reflected image emerges as I approach, though it can never move in front of the golden text. I am stuck in a state of dissociation; there is a barrier between me and myself. Moreover the shape of the mirror reminds me of mourning portraits, which were often housed in oval frames. I linger in front of the work, until I become an integral part of it, and when I submerge back into the distance, it is not the artwork but I that disappears.

Adrian Piper: ‘Everything #4,’ 2004. Oval mirror with gold leaf engraved text in mahogany frame. Edition 8 of 8. 13″ x 10” (33 cm x 25,4 cm) // Collection of the Adrian Piper Research Archive (APRA) Foundation Berlin. © APRA Foundation Berlin. Photo credit: Timo Ohler

Representing the body, however, is not always a subversive or critical act. It won’t necessarily solve issues of prejudice or discrimination because the person is reduced to an image, which functions more like a brand, or a projection surface for fantasy. Visual art, in its lost monopoly on images, often appropriates the tools of fashion and pop culture not only as a pragmatic strategy but perhaps also as a sign of concession. This is the ambiguous position of Arthur Jafa and Cyprien Gaillard. Both use seductive soundtracks, extraordinary images and both seem to cultivate an aesthetic at least partially derived from youth and club culture. Though Jafa’s danceable media mash-up, ‘Love is the Message, the Message is Death’ (2016) might be understood to embody the cathartic coping mechanisms used to deal with the brutal reality of white supremacy, it also renders black suffering perversely aesthetic. Gaillard’s film, ‘Cities of Gold and Mirrors’ (2009), portrays crass white American teens during their traditional yearly ritual—the college Spring Break. Their aggressively empty faces and well-fed white bodies poised against a Cancun landscape easily dissolve into objects of contempt. And, though I feel savvy and even superior for not being a predatory tourist, I am lulled into enjoyment by an augmented soundtrack poached from a 1980s cartoon. Eventually, the film may as well just be a beautiful music video, complete with dolphins, the flashing lights of a nightclub, and what looks like an interpretative dancer in L.A. gang attire, twisting amidst Mayan ruins.

Arthur Jafa: ‘Love is the Message, The Message is Death,’ 2016, Video, 7′25″, Color, sound. Video still // Courtesy of the artist and Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, New York/Rome

Cyprien Gaillard: ‘Cities of Gold and Mirrors,’ 2009, 16-mm-Film, 8′52″, Color, sound. Film still // Courtesy of the artist and Sprüth Magers, Berlin/London/Los Angeles

Of course, art should not be about being on the right side, and, if anything, does better to complicate notions of wrong and right. Wojnarowicz’s ‘A Fire In My Belly,’ which features a generous helping of Mexican footage, is, like Gaillard and his American teens, also guilty of what Alexander Chee calls “aesthetic tourism.” In the accompanying catalogue, Chee writes that Wojnarowicz used “another culture’s symbols to say something about [his] own.” Indeed, in Cynthia Carr’s biography, Wojnarowicz is remembered as saying he found less of the “pre-invented world” in Mexico, which, as seems obvious now, had everything to do with his own foreignness rather than Mexico’s lack of societal structures. But if this is the case, can one experience life beyond the punishing rituals of Wojnarowicz’s pre-invented world?

To this end, the catalogue is a necessary supplement to the show. A different writer was tasked to respond to, with the exception of Trisha Donnelly, each artist’s work. The 36 responses result in a variety of texts, some of which are very critical. Rather than explaining or elevating the exhibition to a moral or activist position, the catalogue becomes a space of reaction and discussion. Together with the exhibited works, it creates a forum in which different types of violence are portrayed, refuted and even acted out. In this scheme art is fallible, but it is a safe space, perhaps even a ritualized space, where social practices and prejudices can be embodied, dismembered and even sublimated. However, rather than forming and reifying new rituals to replace them, art questions them and operates at their interstices.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Ritual.’ To read more from this topic, click here.

Exhibition Info

Julia Stoschek Collection Berlin

Group Show: ‘A Fire in My Belly’

Exhibition: Feb. 6, 2021–Dec. 12, 2021

Admission: € 5

jsc.art

Leipziger Straße 60, 10117 Berlin, click here for map