by Urszula Usakowska-Wolff // Mar. 29, 2021

Art historian Tina Sauerlaender works internationally as an independent curator. She has curated exhibitions on virtual reality in New York (Parsons/The New School), Toronto (Goethe-Institut) and Basel (Haus der elektronischen Künste). She is the artistic director of the VR Art Prize, and co-founder and director of the international exhibition platform peer to space. Sauerlaender is also co-founder and CEO of the international online research database for VR art, Radiance VR. We spoke to her about how virtual reality can expand our understanding of traditional media.

Banz & Bowinkel: ‘Poly Mesh,’ 2020, nominated for the VR Art Prize by DKB in Cooperation with CAA Berlin // © the artists

Urszula Usakowska-Wolff: You were one of the first curators in Germany to discover the potential of VR art and, in 2010, you founded the international exhibition platform peer to space to give new artistic forms a space for presentation and to facilitate the exchange of opinions. As an art historian who also studied Bavarian ecclesiastical history, why did you venture into this unknown territory? Did you already have an inkling back then that digital art would prevail?

Tina Sauerlaender: As a historian, my understanding of new media is a very conscious one. I learned what it was like when photography, film or video were new and how they became established in the long run. Photography has taken over 60 years since its invention to slowly establish itself as an artistic medium. Artists always pick up the media of their time and start working with it. Computer art has been around since the late 1950s, as long as computers have existed. Internet art came into existence in the early 1990s, the same time as the internet became accessible to the public. However, many artists experimented with the possibilities of global communication decades before that.

When I started devoting myself to digital art in 2010, it was not new, but it was far from structurally embedded and established. Museums, art history departments and art universities started taking the medium seriously very late. In 2010, the former Viennese artist collective VVORK—consisting of Oliver Laric, Aleksandra Domanović, Georg Schnitzer, and Christoph Priglinger—curated the very first peer to space exhibition in Munich under the title ‘Multiplex.’ On the large windows of the exhibition space, they projected digital moving images of 31 international artists, including Paul Chan, Agnieszka Polska, Rafaël Rozendaal and Annika Larsson. It was clear to me at the time: as a contemporary witness of the digital transformation, I wanted to actively participate in what was happening and contribute to the establishment of new media in art, as well as to preserve this knowledge for future generations. Because this is important to me, I stuck with digital and continued to expand my activities. Virtual reality was the next logical step that came about quite automatically.

‘Multiplex,’ 2010, exhibition view, curated by VVORK, presented by peer to space, artworks by Billy Rennekamp, Agnieszka Polska, Carla Edwards, Paul Chan // © peer to space

UUW: In times of pandemic, private life is predominantly confined to one’s own four walls, and public life, including cultural life, takes place on the internet. The Word Wide Web has become a huge showcase. Opera houses and theaters use it to stream their performances and stay in touch with their audiences. Museums and other art institutions seem to be surprised by the new situation and rarely, if ever, use the possibilities of digital mediation. Why?

TS: It’s easier for opera houses and theaters because the stage and the audiences are usually separate, so the experience is similar to what it has always been: you sit in a chair and watch the performance, but now you do it from home. It’s also easier for users to participate because everyone knows how to play a video and how to scroll through a website. Those are big advantages. But when a museum is thinking about showing a virtual exhibition space on the internet, these simple skills are not enough. In a physical museum, everyone knows: you go to the ticket office, buy a ticket, and then you look at the exhibition. But online it’s different. You’re suddenly standing in the digital space and you have to move, but you don’t know how.

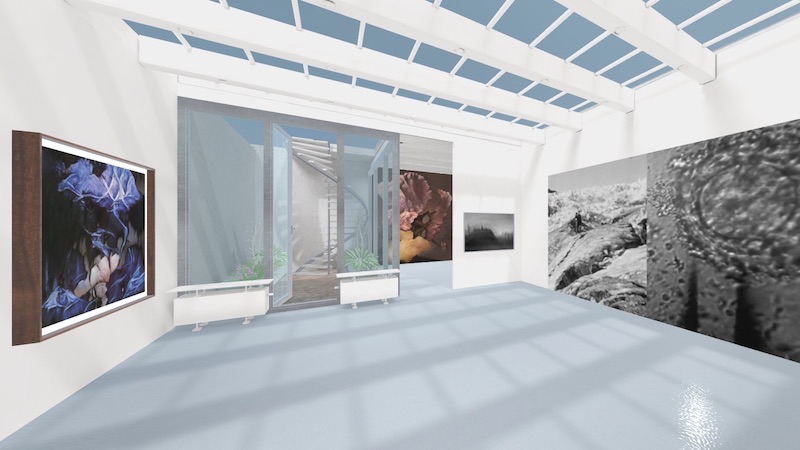

We opened the Priska Pasquer virtual gallery on the Mozilla Hubs WebVR platform in February, where I presented Berlin-based artist Ornella Fieres in the first exhibition in the One To One – one curator meets one artist series. We noticed that at the beginning the visitors didn’t know how to move in the virtual space. It sometimes takes up to ten minutes to get familiar with using the virtual room. As a curator, it is important to be aware of this and implement measures to ease the access to virtual spaces. However, I am happy to see that major museums are discovering digital and online tools to meet virtually, present exhibitions, or simply conduct an informal and spontaneous talk on Instagram. Museums are now looking to make up for years of neglect. Museums need to consider which virtual platforms are best for them, how much money they need to spend on them, who has the know-how, and where they can find experts to program their online exhibition spaces, etc. These are questions that have actually been around for 30 years and are only now becoming relevant to traditional museums.

Ornella Fieres: ‘Light shines through the Curtains of Time,’ exhibition curated by Tina Sauerlaender, Priska Pasquer virtual gallery // Courtesy Priska Pasquer

UUW: You are the artistic director of the VR Art Prize, which was announced for the first time on May 5th, 2020 by Deutsche Kreditbank AG (DKB) in cooperation with the Contemporary Arts Alliance Berlin (CAA Berlin). What is special about this art prize and the exhibition you curate at Berlin’s Haus am Lützowplatz, where the works of the nominees for the prize will be presented from April 17th to June 6th, 2021?

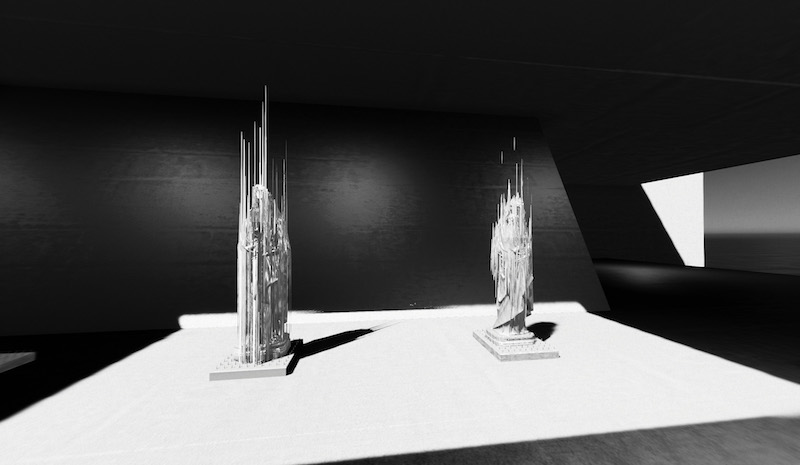

TS: The VR Art Prize of the DKB in cooperation with CAA Berlin is the first art award for virtual reality in the field of visual arts with an institutional exhibition in Germany. The focus is on the exploration of the artistic potential of new technologies as well as the exploration and critical reflection of their impact on the individual and society. From the 104 artists who applied, our jury of experts selected Banz & Bowinkel, Evelyn Bencicova, Patricia Detmering, Armin Keplinger and Lauren Moffatt, who each received working grants for four months at 1,000 Euros each and will show their work in the exhibition ‘Resonanz der Realitäten (Resonant Realities).’ On May 7th, three VR Art Prizes will be awarded, endowed with a total of 12,000 Euros each. The prize (including the working grants), endowed with a total of 32,000 Euros, and on top an institutional exhibition, is intended to contribute to the structural establishment of the medium in visual arts and to enable a museum institution to organize an appropriate exhibition. The VR Art Prize is to be continued in the coming years. And the response to the open call—104 exciting submissions—is really impressive for a medium that is still rarely taught at German art academies.

Armin Keplinger: ‘The ND-Serial,’ 2021, nominated for the VR Art Prize by DKB in Cooperation with CAA Berlin // © the artist

UUW: Is VR art the genre of the future?

TS: I wouldn’t necessarily call VR art a genre, I would just call it a new medium. Since 2015, the new generation of VR headsets from the U.S. technology company Oculus or the Taiwanese company HTC have been available and have developed rapidly. VR art, for example, is also experiencing a significant upswing. In the last few years, museums have been showing VR art, and art academies have started to set up corresponding degree programs. Darmstadt University of Applied Sciences now offers the degree program Experience and Narrative Design in Expanded Realities. I founded Radiance VR in 2017, together with Philip Hausmeier, who is a professor there. The international research platform for VR art presents documentations of over 170 VR experiences by international artists. To do justice to the history, we also created a separate section here about the pioneering works in VR art in the 1980s and 1990s.

UUW: Given the accelerated development of VR art, is traditional analog art a discontinued model?

TS: Digital media will not replace analog, but it is exciting for many artists from other fields, such as painting or sculpture, to work with virtual reality, because the laws of physics don’t apply there. Almost all artists who work with VR started with traditional media because they couldn’t study VR at art academies. They got into VR because they realized: Sculpture, installation, or painting function brilliantly in virtual space. There’s no gravity, you can choose the material completely, mimic the surfaces, you don’t have to work with toxic substances. And, in addition, virtual space offers new possibilities and interactive tools for artistic creation and expands the forms, aesthetics and comprehension of all traditional artistic media.