by Berlin Art Link // July 21, 2021

In the words of German-Egyptian sculptor Dr. Gindi, “infinity is the main thing worth attaining in life.” The artist’s adopted name reflects her personal heritage as well as her professional training as a medical doctor, but sculpture is where she finds a way to explore and express the infinite aspects of humanity. Through clay and bronze, her works often reshape aspects of as well as the entire human body, and they bear titles like ‘Transfigured Immortality,’ ‘The Plague,’ and ‘The Fateful Choice.’ As such, the sculptures speak to our collective and individual—but nevertheless unavoidable—suffering. Beyond that, however, they also hint to what might come after, to infinity.

“The ancient Egyptians knew that humans have vast capacities and talents, and by cultivating them we become closer to the fulfilment of a magnificent human destiny,” Dr. Gindi says. “We can even create our own reality: a whole new cosmos that evolves its own stars.” Here, we speak to the Switzerland-based artist about how her medical training informs her practice, what brought her to the concept of infinity, and how her time living in Berlin continues to influence her work.

Dr. Gindi: ‘The Painter,’ 2020 // © Dr. Gindi

Berlin Art Link: We’re curious to know more about your chosen name, “Dr. Gindi.” Can you explain the significance of this name and why you chose to adopt it?

Dr. Gindi: I was brought up in Germany in a multicultural environment with Egyptian roots. “Dr. Gindi” captures the sense of my real name—“Gindi” is a common family name in Egypt—and in addition there is my doctoral title, as I am a trained medical doctor. Serendipitously, Egyptian culture is often an influencing factor in my sculptural practice. The remarkable gifts of the Nile, with its annual flood and unique fertility, encouraged the ancient Egyptians to strive for infinity to overcome chaos; this is a delicate thought that recurs in my work.

BAL: As you’ve just mentioned, you’re professionally trained in medicine but you’re also a trained sculptor. Which came first? How did one lead to the other?

DG: Mortality, and its grim forerunner called disease, had accompanied me ever since I studied and practiced medicine. An outburst of artistic necessity after working as physician in a hospital set me on the path to become a sculptor. I experienced humanity’s pain while succoring ailing bodies suspended in the netherworld between hope and surrender. With my sculptures I aspire to show that the infinite unravels both time and space, and I want to contrast the biological sphere of humanity with my own three-dimensional conceptions.

Dr. Gindi: ‘Beaufort 7,’ 2020 // © Dr. Gindi

BAL: How do you think the worlds of medicine and sculpture influence or inform each other, particularly in regard to your own practice?

DG: My works often exhibit a fascination with the human body in all its visceral detail, including an abundant use of flesh and bones. The connection between art and medicine has been made for millennia. It can even be found in ancient Egyptian mythology: Heka was the god of medicine and of the creative act. As such, he was viewed as deity of emphatic magic. Likewise, my sculptures have become a manifestation of duality, a balance of body and mind, of gravity and lightness, and most importantly, of essence and appearance. I am trying to lacerate the periphery of the human shell to reveal the core in order to understand what holds humanity together in its innermost folds.

BAL: What draws to you the subjects of immortality and infinity, especially in relation to the human body?

DG: Our bodies are fragile and transient chattels, but also cocoons to probe the unboxed future. Physical death is certainly inevitable: at one point, the pinworms will arrive and eat our flesh and only some ashen bones will remain. But what if we could choose our lifespan, and the moment we slide into infinity? What if we could choose an unending existence or even the absence of suffering? The ancient Egyptians believed that death is not the end of life but rather the assumption of a different dimension. When physically dead, our embodiments might still be in motion—but only if we want. It depends on us; it is not a given. My sculptures suggest that the roads to infinity must be fought for.

Dr. Gindi: ‘The Fateful Choice,’ 2021 // © Dr. Gindi

BAL: Your work is often rendered in clay and then bronze. What drew you, firstly, to sculpture (rather than, say, painting or drawing), and secondly, to clay and bronze as materials?

DG: Sculptures present themselves in the dimensions of height, width, and depth. They occupy physical space and can be perceived from all sides and angles. That’s what always fascinated me—I am drawn to three-dimensional work, to sculptural artefacts. You can touch the skin of your sculptures; it is part of you, and it embodies and imbues the personality and gesture of the sculptor. My hand-built figures are gestural and there is a give and take between the clay and me. Clay is a very assertive material: it behaves erratically, it debilitates me. But it gives so much back to me in its earthy permanence. The clay figure is then cast into bronze, which I chose for its permanence and its vibrational traits, as well as its ability to lock and reveal heightened zeal. Bronze expresses best the potential infinity of our existence.

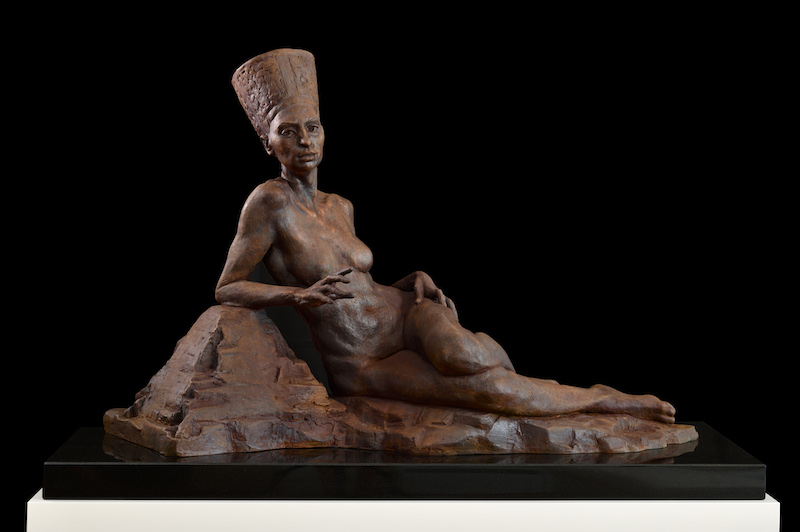

Dr. Gindi: ‘Transfigured Immortality,’ 2020 // © Dr. Gindi

BAL: We particularly like this quote of yours: “I have spent my entire life […] trying to understand why certain phenomena appear the way they do and why I interact with them the way I do.” Can you give an example of how you think this plays out in your sculptures?

DG: My work might be difficult to pin down, as I resist a signature style, but yes, I always try to understand why certain phenomena appear the way they do. Take ‘Transfigured Immortality,’ for instance: the piece originated in a phase of mourning after the death of a close Egyptian relative. I wanted to explore the essence of immortality in ancient Egyptian thought. The piece depicts a graceful lady—some might say a Pharaonic queen—in the prime of her life, leaning on her last place of rest. She reflects upon the dark spots of her existence, rimmed by scattered light glistening from the deep. By accepting the world beyond, she illuminates her present life in dignity. It is not eternal death but the lightness of infinity that I try to capture in that sculpture.

BAL: Although you currently live in Switzerland, you also lived in Berlin for a while. Can you talk about how Berlin was or continues to be inspiring and influential for you?

DG: I have lived in a number of countries for study and work, but my time in Berlin was extremely influencing. I lived there for seven years studying medicine—prior, during and after the fall of the wall. I remember strolling alongside the wall on a late summer evening when I suddenly conceived the thought of boundless infinity while physically enclosed by this hellacious barricade around me. And the thought to overcome outer and inner confinement in order to unfetter our creative will. The belief in infinity has gripped me ever since.

Artist Info

Dr. Gindi, ‘Interstellar Dilemma,’ 2020 // © Dr. Gindi