by William Kherbek // Jan. 7, 2022

The American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.” Living in the age of Web 2.0, this capacity feels almost like a prerequisite rather than a test. The 21st century’s third decade is feeling substantially more like an age ruled by Lewis Carroll’s White Queen from ‘Alice in Wonderland’: we are all required to believe at least six impossible things before breakfast, and, ideally, post about our experience, too. The contradictions, insolubilities and miasmas incubated by contemporary digital culture are the fuel on which the 0x Salon runs. Begun in the darkest days of the 2020 lockdown and organised by the artist and philosopher Wassim Alsindi, a trained physicist and chemist, the Salon has become a port of call for thinkers and creators across media and discourses to come together to engage with the strange attractions and repulsions of digital culture. Alsindi’s project is expanding from the salons themselves to a diverse range of cultural outputs in the new year. We spoke with Alsindi about the beginnings of the Salon and the infinite directions it may take.

‘The 0x Salon,’ Generated with VQGAN+CLIP from a photograph by Wassim Alsindi, 2021

William Kherbek: How has the 0x Salon opened up aspects of the digital culture discourse in your estimation? Have you been surprised at all at the directions it has taken in terms of discussions and viewpoints?

Wassim Alsindi: The 0x Salon is an upstart event series comprising intimate post-disciplinary discussions. We’ve been going since February 2020, holding offline and online conversations about unusual topics with diverse attendees. Starting an event series in a pandemic sounds like an unwise idea, but there you go. A community of researchers, artists and theorists has formed around the Salon, and we collectively author technical and creative works based on topics that are addressed in the events. In the past few months, we’ve launched a residency programme, developed a discourse card game, published speculative scripture and spawned an improvised radio play.

We’ve had some pretty fiery conversations about tokens, networks and blockchains. It is quite a natural topic for us to discuss given many of 0x Salon colleagues’ familiarity. We did our best to avoid the returning hype around crypto for quite a while, as initially we were hosting the salons to get away from our everyday preoccupations. It does seem that the zeitgeist has caught up with our daily lives, and seemingly everyone wants to talk about NFTs, crypto-art, DAOs, tokens and the rest of it.

Last winter, we hosted a series of ecologically-oriented conversations under the banner ‘The Forest from the Trees.’ All of a sudden, illustrious colleagues—such as Anna Tsing, Patricia Reed, Keller Easterling and Suhail Malik—were coming along to salons. In those conversations, I felt we were all pulling in the same direction: we all want a planetary ecology! However, when we moved onto discussing Bitcoin in the ‘The Indifference Engine’ topic things felt a little different. On one side is ecology and, the other, capital, and it’s almost as though Bitcoin, through proof-of-work, mediates a zero-sum game between the two. There are two sides to the same coin, in an epistemic sense.

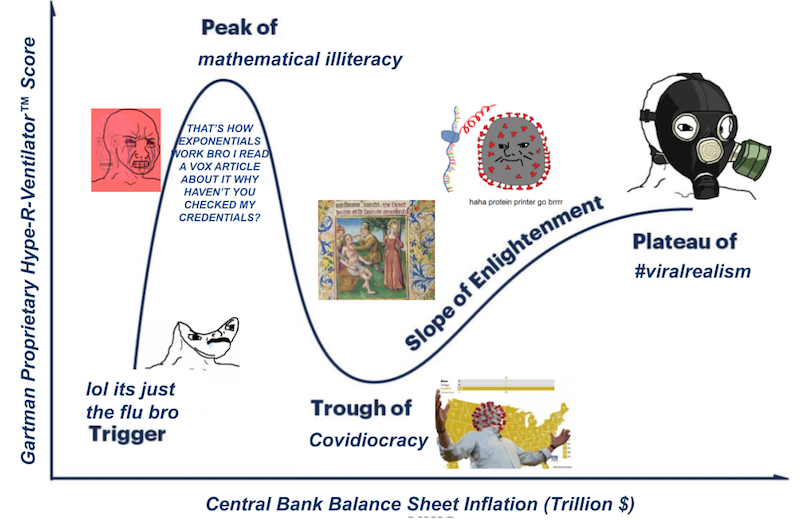

Wassim Alsindi: ‘Viral Realism Hype Cycle’, 2020 // Courtesy of the artist

WK: You recently held a Salon about memes. What were some of the takeaways you had about the ways memes are changing, and have already changed, the ways people communicate?

WA: It appears as though we’re in the midst of a post-linguistic paradigm shift, and something closer to a semantic and/or semiotic communication mode is emerging. Memetic discourse has been around in some form for a while, but far too often the conversation starts with Richard Dawkins and it proceeds through Susan Blackmore, and it goes wherever else filtered through those limiting, conservative “boomer” lenses. We’ve done three salons on memes, and each time as we unpick cultural, historical, semiotic, political stands, we uncover far more questions than answers.

Emojis and memes take on a great significance in bridging communication gaps and chasms across cultures and languages, and there are interesting cross-cultural analyses which, to me, seem to be a rich seam of contemporary, radical post-colonial perspectives. As with the legends, our forebears recounted sitting around the campfire, these modern meta-myths also give people a sense of belonging. Contemporary analysis of memes is still pretty new. Some members of the 0x Salon community also work at major cultural institutions as meme correspondents, and that might become a more common job description going forward. Perhaps the meme is the next generation of a quantum of culture, a yet-more-virulent strain of post-linguistic communication eating everything that went before it, just as cryptocurrencies are the most virulent strain of capitalist modes of exchange to date, eating everything that went before.

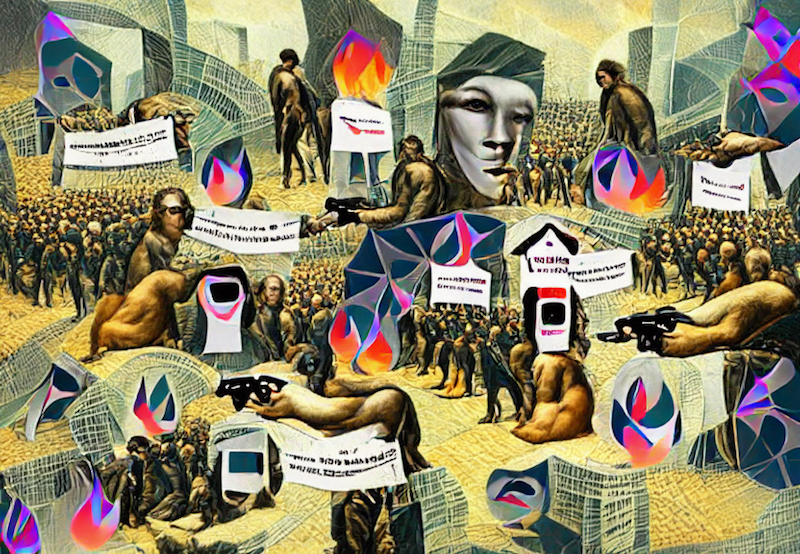

Wassim Alsindi: ‘The Revolution Will Not Be Tokenised,’ 2021, Generated with VQGAN+CLIP // Courtesy of the artist

WK: On NFTs, I wanted to ask about the fetishisation of ownership they seem to be fostering. The historical art discourse around collection has centred on connoisseurship. While there are definitely elements of connoisseurship to NFT collection—or at least recognisable features of “collector culture” about it—their true “value” often appears to be in the capacity to display “ownership” in a culture where increasingly people own fewer cultural products (e.g. playlists over vinyl, streaming rather than owning films). Could you speak about some of the potential consequences of this shift from your viewpoint?

WA: Mitchell Chan wrote a piece a few months ago where he suggested that NFTs have completed the separation of the art form from the commodity form. This might be why we’re seeing artworks of dubious merit trading as extremely valuable commodities. These two priorly entwined aspects have almost been disconnected: the artistic work from the speculative potential of the object.

A line of inquiry that I’d like to explore in the future lies within the interplay of the artwork, the collector, the curator and the creator in terms of the semantics around object ownership, scarcity and rights to interact, exhibit or transact. The relationships of these parties to the product, and to the process of creative production are rather peculiar. With today’s NFT culture, the concretised, reified object is the only thing that has any worth in the eyes of the market. By implication, anything outside of, or before, that is completely externalised, destroyed or ignored. The labour of the artist, the conceptual work, the technical work, the creative work; the “doing” has been largely removed from the bargain.

If you go back through the history of art more generally and look at the relationship between the artist and the patron—whether the artist wanted that or not, the patron might have been involved in the process: guiding the direction, the content and the dissemination. Today’s digital artist disappears into the void, creates work, it is transmitted onto a virtual platform, and then on to a secondary market. There’s often very little connection between the possessor of the object and the artist.

On the other hand, there are some exciting avenues, possibilities and affordances opening up that make new artistic interventions and strategies possible. A small number of artists are working on conceptually and aesthetically novel projects that I think are really exciting. I would point people towards several of Sarah Friend’s recent artworks, in particular ‘Off,’ which is an NFT series of black oblongs in the dimensions of different device screens. That, in itself, is all well and good, but what’s really interesting about this project is that each of the 255 NFTs also contains a fragment of a special “collective key.” Two thirds of the owners of the entire supply of ‘Off’ NFTs have to coordinate to unlock another, secret piece of art. The edition embeds within the collector community a coordination game that’s positive sum. To see advanced threshold cryptography like Shamir’s Secret Sharing (SSS) being used in crypto-art at this early juncture is, in my opinion, quite remarkable.

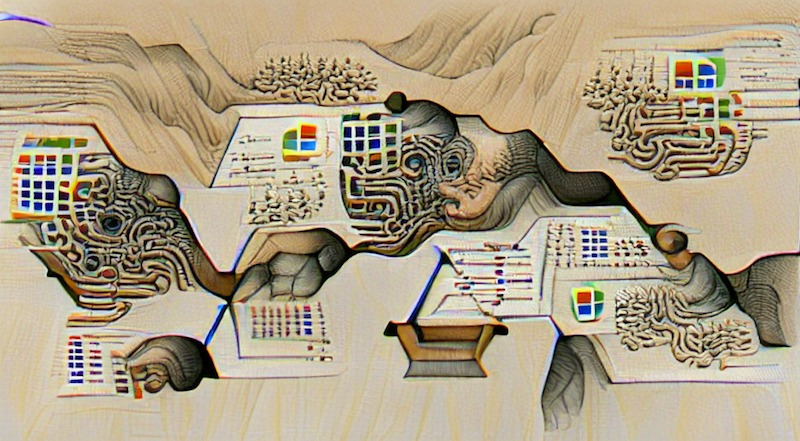

Wassim Alsindi: ‘The hidden bias of a machine learning training set,’ 2021, Generated with VQGAN+CLIP // Courtesy of the artist

WK: Your own production often involves GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks) and other machine learning-based technologies. These technologies have been used to challenge historic notions of creativity or individual authorship. I wonder how you view the creative potential of these entities as destabilising certain long-held and lionised conceptions of creativity?

WA: It’s somewhat disingenuous for a human to claim total ownership or creative agency over working in these process-based modes. It’s more a matter of having a machine and feeding it inputs. Having a background in experimental quantum physics, working with generative graphical learning systems gives me the sense of being back in the laboratory. A massive, complicated instrument, a literal or metaphorical black box, with which the machine operator intuitively navigates a parameter space. My doctoral research employed a technique called ultrafast spectroscopy where a laser is used to create an unstable piece of matter, and then another laser is used to interrogate and characterise the subject over very short time scales. In creating one of these ephemeral states, no one can know how it will behave or evolve. The machine operator is not in control of these phenomena.

I see machine learning tools functionally being somewhere between a looking glass and a mirror. What you tease out of them depends on what you bring to the party. This might be provocative, but it seems to me that there’s a reason why so much of the outputs generated through this co-poetic mode often with GPT-3 and GANs is so uninspiring and uninteresting: the ease of generation is accompanied by a lack of imagination. We get what we give: reflections of whatever the operator is providing it with.

I started experimenting with semantically-driven image generation in the summer, and got unusual, freakish results immediately. I assume one of the reasons for this is because I’ve been writing quite a lot of abstract text in the last 12 months, mostly poetic and philosophical critiques of technology. It’s been very interesting to provoke the algorithm with critiques about themselves, forcing them to address their own shortcomings. You can take a GAN head-on by instructing it to paint a picture of its own biases. I’m trying to confuse it, to disorient it. It sometimes feels like disarming a weapon, but we also need to retain some collective humility here. I don’t feel that anyone who uses a GAN could really be thought of as a “creative genius” by those outputs alone. The GAN-wrangler is more akin to a partner in a binary star system, two stars orbiting each other in a gravitational dance, or as a bystander regarding a black hole, towards which one is funnelling material and seeing what disordered forms emerge.

This article is part of our feature topic of ‘Digital.’ To read more from this topic, click here.