by Noushin Afzali, studio photos by Ériver Hijano // June 7, 2022

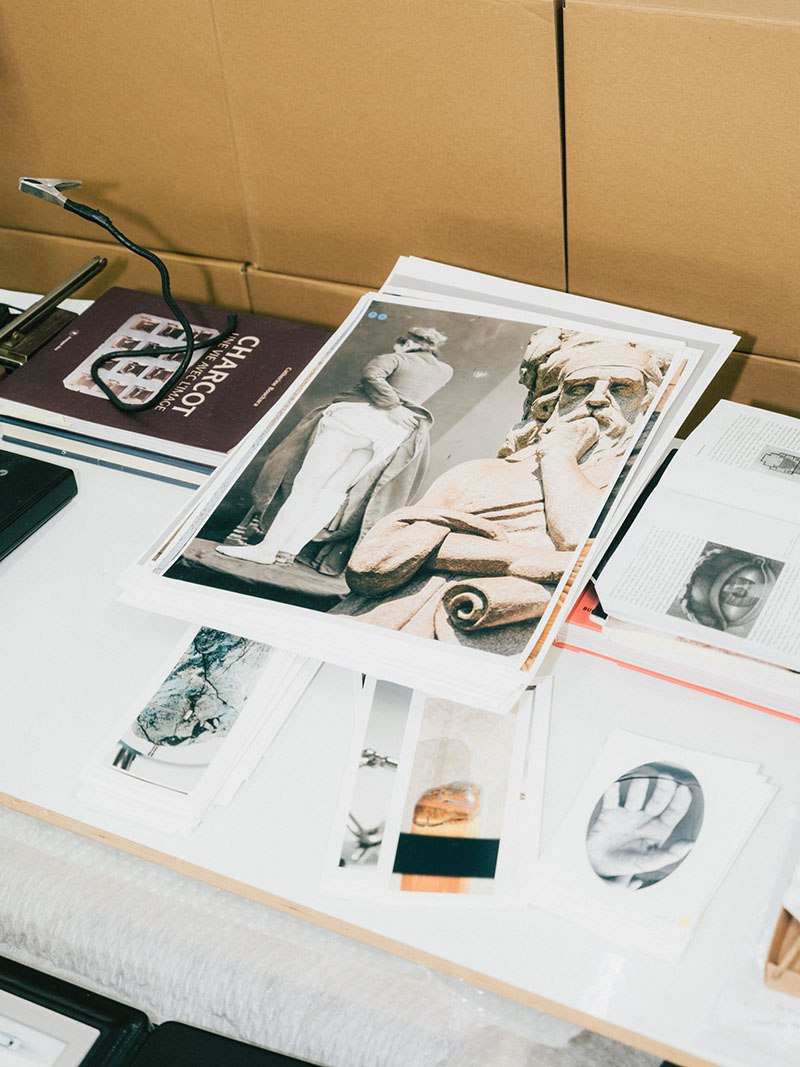

Ilit Azoulay’s well-lit studio space is a welcome contrast to the bleak Berlin sky outside. Upon entering the space, we hear the recording of a warm, powerful female voice singing in Arabic. Numerous plants animate the studio—several sitting on the windowsill, a couple hanging from the ceiling in the middle of the room. The studio walls are scrupulously bedecked with hundreds of black and white photos. These photos are the source material for ‘Queendom’ (2022), the artist’s exhibition in the Israel Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale curated by Dr. Shelley Harten. Curious to learn more about this and other projects, we sit down together over cups of freshly brewed cardamom coffee on this somewhat gloomy day in May.

‘Queendom’ is an exhibition of large-scale panoramic photomontages, a sound installation produced in collaboration with light-language channeller Maisoun Karaman, and architectural interventions. The source for the project was a nearly forgotten archive of photographs of mediaeval Islamic metal vessels taken and collected by the Austro-Jewish-British art historian David Storm Rice (1913-1962). Hundreds of archival boxes containing black and white silver prints and around ten thousand negatives of mainly macro photographs of vessels and objects are stored away in the Museum of Islamic Art in Jerusalem as part of the Rice archive. Azoulay first found out about the archive in 2020, when she received a call from Na’ama Brosh, curator emeritus for Islamic art at the Israel Museum, who told her that it was in danger of being thrown away.

Azoulay’s work often focuses on gaps in the historical record, both literal and perspectival. The soon-to-be lost Rice archive was an example of both. Compiled through a male, white, European perspective, Azoulay wished to subvert the gaze and give power to the “missing voices of history.” “As a new platform of opportunity to look at history, ‘Queendom’ recounts history from a feminine perspective,” says Azoulay. To achieve this, she engaged in a process of scanning, cropping, and editing the photos into new data carriers, then digitally “welding” them onto scanned metal plates. “‘Queendom’ challenges the male-dominated and national sets of knowledge and information transfer,” adds Azoulay.

This knowledge is also challenged architecturally, on the level of the Israel Pavilion itself, which Azoulay transfigures to become part of a discourse of female empowerment. Built in Bauhaus style in the early 1950s, shortly after the emergence of the Israeli state, the pavilion’s Eurocentric architecture is evidence of the country’s wish to be perceived as part of the Western art world, all the while ignoring its kinship to the Middle East. Azoulay explains that, as a Jewish person with Moroccan roots, she felt that the pavilion’s architecture “misses any representation of the Middle East, reflecting back to the flat idea of a melting pot instead of showing proudly the many cultures arising from all parts of the Middle East.” To counterbalance this, Azoulay added Middle Eastern elements to the space—covering the ceilings and columns to give them a softer, fabric-like appearance, opening a gateway to the eastern entrance, and adding a garden with a fountain to the rather neglected backyard of the building. For the artist “‘Queendom’ offers a non-patriarchal and non-territorial vision that transforms the pavilion into a place where art takes on power.”

As an interdisciplinary artist, Azoulay incorporates numerous mediums in her projects, including photography, concepts, architectural interventions, and elements of sound, video, and performance. Her artistic practice centres on composing images grounded on data collected from oral histories, storytelling, rigorous research and investigation. Her studio, with its full bookcase and piles of documents on tables, is evidence of her meticulous research methods. Azoulay draws our attention to an artwork situated on the right-hand side of the room to illuminate how she usually works with acquired information. ‘Vitrine No. 4: (Take, for instance, this) true story’ (2017) is a large-scale collage that depicts, among other things, a stone in the shape of a pomegranate. The photo is part of a project called ‘No Thing Dies,’ Azoulay’s first solo exhibition in the Israel Museum, Jerusalem. For this project, Azoulay engaged in three years of research in the archives and storage rooms of the museum (2014-2017) and collected individual and personal stories from the staff of various departments, including curators, archivists, and conservators. These conversations later gave shape to large-scale assemblages in which photographs of objects and artworks from the collection of the museum were collaged together. Most of the pictured items hadn’t been displayed in years; to this day they remain nearly forgotten in the institution’s storage spaces. By bringing attention to the forgotten objects Azoulay questions the power structures inherent in any system and stresses the importance of discovering “silenced histories”— a theme she returns to time and again in her other projects.

The aforementioned pomegranate—a recurring object in the “No Thing Dies” series—emphasises the significance of crediting an object with its actual history and the consequences of its removal. Made from a hippopotamus tusk in the form of a pomegranate and only 43-mm high, it bears an inscription in paleo-Hebrew that reads “Sacred to the priest of the House of God.” Considered once by many as “the Mona Lisa” of the Israel Museum, it was reputed to be the sole surviving relic of the first Temple of Jerusalem. Discovered in 1979, it gained national importance only to be discredited as an imitation years later. Since then it has been stowed away in a cardboard box in the museum’s archive.

Like Azoulay’s intricately archival practice, the conversation dives into one rabbit hole after another. Just as we are about to leave, a new conversation takes form as my eyes are drawn to a sturdy, greyish black frame that holding three pictures—a close-up of a hand on the left, an unrecognisable object under a magnifying glass on the right, and a half-naked woman facing a wall in the middle with the words “What is the matter? Where does it hurt?,” inscribed on the side. The photographic triptych belongs to ‘Mousework,’ (2021) Azoulay’s project made during lockdown in Berlin. Led by personal curiosity, the artist conducted extensive research on the history and documentation of “female hysteria.” Historically regarded as an exclusively female condition, the social construct of female hysteria was employed to maintain the patriarchal order. Though no longer recognised as a medical disorder, the word and its related imagery still occupy a significant place in the everyday discourse of domination. The French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot was a pioneer in the use of photography in documenting hysteria and established a photography lab at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital in Paris exactly for this purpose. Azoulay extensively investigated this phenomenon as depicted by Charcot in the 19th century. In the course of her research she also learned of the different ways that Charcot’s legacy survives to this day. Many images of “hysterical women” (over 3,000) are sold by stock photo companies, explains Azoulay, and used in advertising by, for example, pharmaceutical or insurance companies.

In total, ‘Mousework’ consists of 35 photographic triptychs presented in vacuum formed frames and made according to a predetermined logic: the left oval picture comes from the Salpêtrière hospital photography archives, in the centre are collages from online image banks, and photos of objects found by Azoulay on her walks in forests outside of Berlin are always on the right. Central to the project was the “brutal and manipulated use of the camera as a machine that provides proof and the connection to the medical financial system as a triangle that still supports old definitions and stigmatisation of women.” Here again, Azoulay brings to light “the missing voices of history” (close to 5,000 female patients were hospitalised against their will) and demands a new narration outside of the dominant patriarchal discourse.

For Azoulay, photographs, collages and installations can capture the ambiguity of objects detached from their original purpose. Relinquished from their old roles, they can serve to reconstruct histories and help us rethink their narration beyond the dominant patriarchal order. Creating “a multi-dimensional space of all possibilities,” her artistic practice encourages new ways of perception by questioning and re-examining how visual information is processed.