by William Kherbek // May 26, 2023

This article is part of our feature topic Aging.

The passage of time is the occluded subject of every film. The person who arrives at the beginning of a film is never exactly the same person who leaves at the end of it. Thus, every filmmaker becomes a more or less conscious temporal philosopher. What does being within the strange temporality of film mean? And what does the passage of time for the viewer and the maker of a film mean within and beyond the creative work itself? This relationship is what has always fascinated me about the ways in which John Smith’s films deal with time, memory and the process of aging. Smith has been making films for more than half a century now, and his works examine how time inscribes itself on a work, on a place and on the body itself.

John Smith: ‘The Girl Chewing Gum,’ 1976 16mm film, transferred to HD video, black-and-white, sound, 12 minutes // Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles

Time and film (and art more generally) are uneasy companions. A film ages, both physically and discursively, but the time represented in the film or artwork remains stable. The image, for example, of a corner in Dalston in east London as featured in Smith’s early work ‘The Girl Chewing Gum’ (1976). The city depicted in the image is recognisable, but only just, and indeed the distance in time is perhaps the most palpable element of the film to someone who knows that corner. In fact, one would have a heroic task in connecting the past version of the city with the contemporary one. This is an idea that occurred to Smith himself, who revisited the same corner where ‘The Girl Chewing Gum’ was filmed in 2011. The resulting film, ‘The Man Phoning Mum’ overlays new footage from the site with the original film. Discontinuities become literally written into the fabric of the new film, and pose a fundamental question about the difference between the way time affects people and places: people age, but do cities age?

John Smith: ‘The Girl Chewing Gum,’ 1976, 16mm film, transferred to HD video, black-and-white, sound, 12 minutes // Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles

John Smith: ‘The Man Phoning Mum,’ 2011, HD Video Super Imposition on Blu-ray disc 11 mins 35 secs // Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles

Cities accrue history, or they erase it according to the vagaries of capital. Berlin, too, is no stranger to the kind of “luxury blight-scape” that has disfigured parts of London. The bulldozing of history in favour of a modernity that will be obsolete before the plaster is even dry on a new building is something that is increasingly familiar across most art metropoles. ‘The Girl Chewing Gum’ and ‘Man Phoning Mum’—as well as a number of other films by Smith, notably ‘The Black Tower’—examine these forms of urban botoxing. “Renewal” is the term regularly used to distinguish changes in urban built environments but this “renewal” comes at a price, and the forms of denial “renewal” entails are not merely psychological. New shiny buildings make no difference to the ancient ground on which London is built. But to those who live there—much like the contemporary Berliners facing what appears to be a permanent construction void in Neukölln—the memories and familiar spaces in which a part of their earlier lives were lived are exiled from the material world entirely.

John Smith: ‘The Man Phoning Mum,’ 2011, HD Video Super Imposition on Blu-ray disc 11 mins 35 secs // Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles

These exiled subjectivities are also central to Smith’s film ‘Blight’ (1996). Ostensibly centring on the construction of a motorway in east London and the ensuing destruction of homes and other buildings to make way, the film combines the voices of local people describing their memories and experiences with images of wrecked buildings appearing on screen. Sometimes the images connect directly, almost (but not quite) illustrating what is discussed. The recurring phrase “kill the spiders” menacingly forms a kind of punctuation for the narrative. A female voice recounts what seems to be a memory of someone killing spiders in a bathroom (in one instance, a broken toilet appears in a frame during this narration), but the “spiders” refrain seems to come unmoored from the status of personal memory and becomes a kind of intrusive thought throughout the film. It is a haunting work. Images flash by of the active destruction of buildings and voices intrude again: “we are sorry that we’ve got to move your mother,” “we’re sorry that we’ve got to destroy the community.” The whole of the work in some ways seems to mimic the manner in which powerful memories imprint themselves in our minds, even as the context from which they emerge fades. Voices in the film that sound “older” reinforce this sense of time and certainties fading away—a materialised forgetting, if such a thing can exist. The sense—which many who have lived with older relatives describe—of the distant past seeming clearer to them than the present moment, infuses the ruinscape of ‘Blight.’

John Smith: ‘Blight,’ 1996, 16mm film transferred to video, colour, sound, 14 mins // Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles

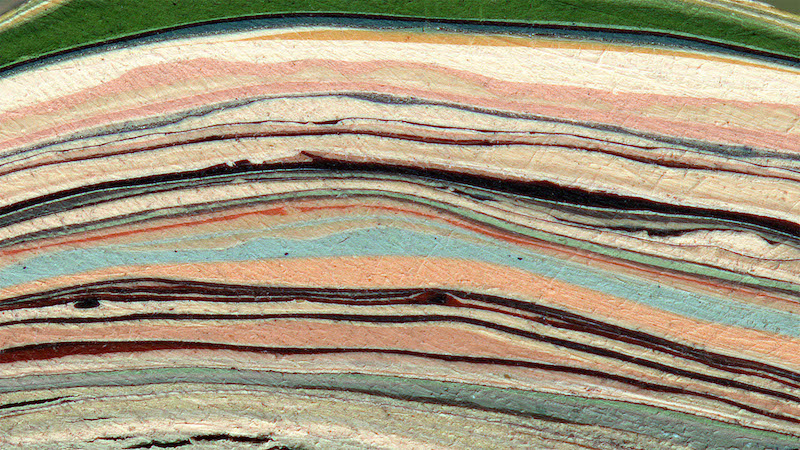

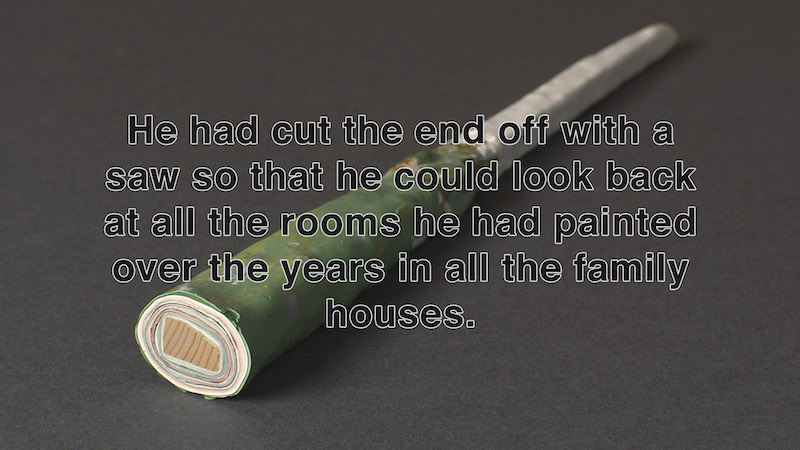

The personalised consequences of aging also feature prominently across Smith’s oeuvre. Smith dissects the experiential ambiguities between “aging” and “growing up.” This occurs, for instance, in his evocative ‘Dad’s Stick’ (2012), which emerged from a conversation between Smith and his father that took place after the elder Smith made a cross-section cut through a stick he’d used to stir various shades of paint over the years, as he redecorated the rooms of their family home. The stick had accreted layers of pigment corresponding to times in young Smith’s life and, in the film, he recounts memories from his childhood as he “grew up” and his father “aged.” The end of childhood and the spectre of mortality looms closer with every jaunty shade in the layers of the stick. The narration consists of random snatches of song—including an ironic rewording of the Socialist anthem ‘The Internationale’ featuring the lyric “the working class can kiss my arse / I’ve got the foreman’s job at last”—performed by Smith as the narrator. Onscreen, text also appears, including tellingly ambiguous phrases that purport to describe his father’s painting choices and styles, but which invite more metaphorical readings, such as the following: “As time passed by, his colours became more muted and his edges became softer.” The aging father becomes mellower with age, or perhaps simply more indistinct in the memory of an aging narrator.

John Smith: ‘Dad’s Stick,’ 2012, HD video, colour, sound, 5 minutes // Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles

Smith’s films often face the anxieties and indignities of aging with a sense of humour, not least the recent ‘State of Grace’ (2019). The film is visually comprised of drawings and diagrammatic images that mimic airline safety guides. Again, Smith narrates an ostensible history of his first time travelling to Ireland by plane and how this experience led him to contemplate all the ill acts he had committed in his life, deducing that he is a “true sinner.” The narrator finds potential redemption in the pilot’s instruction to lean forward and say “Grace! Grace!” in the event of an emergency. The aging narrator of the film, looking back on a lifetime of misdeeds, is relieved by the possibility of grace, but of course the viewer is to understand—and is later informed by the narrator—that the pilot, in fact, is instructing the passengers to “brace” in the event of an emergency landing. Thus, the loss of sensory acuity that comes with age-related physical decline provides a kind of comfort, a capacity to let go. If aging gracefully is in part a matter of learning to let go of things, Smith’s films offer not merely a documentation of that process, but an intense examination of what it means at a human scale.