by Annalisa Giacinti, studio photos by Laura Schaeffer // Aug. 4, 2023

By the time I reach Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s studio in Tegel, I’ve been travelling for about an hour and crossed half of Berlin, and I feel slightly worn out by the early July heat. As I walk in, she promptly offers me a glass of water and we chat for a bit while I catch my breath. She is friendly and hospitable, and her home matches her lively energy. We head to the studio, which is a small bustling room tucked away at the end of her apartment’s hall. Its surfaces are covered in images, drawings, sketches. Flags and printed cloths drape the walls and door; half of the floor is turned into a sort of altar, made of a bed of bright orange straw, on which are scattered more pictures, a crucifix, cosmetic products and make-up, a measuring stick and a medium-sized mirror that leans against the wall and reflects our shoeless feet. “I’ve been looking at religious iconography and why people are so drawn to religion and spirituality. A lot of trans people I know, especially, are drawn to a kind of spiritual way of seeing the world and talk about themselves as deities,” the artist elaborates. She’s been envisaging the idea of “a lost god returning to earth to change the physics of how everything works by centring Black trans people,” and her studio encapsulates the potential of such a prospect.

Brathwaite-Shirley’s practice encompasses film, animation, performance and video game development. A lot of her work is digital and made on screen, yet, she explains, there is a fundamentally analog and tangible component to it. “I work on the wall, I need to see everything and feel it in the room.” She starts every project with a sketch, moves on to collecting references and printing them off, compiling a sort of mood board in order to “gather a type of particular feeling of the direction the work is going in.” As someone who makes a lot of images, both online and offline, she has accumulated an extensive archive that she’s able to access anytime she needs inspiration or a visual input without resorting to external sources. “I wanna make my own book and be able to rip out images from it.”

Being able to visualise her work and let it exist in the environment around her is what helps the artist gauge the share-ability of a project. “When you’re making digital work you wanna make sure the person connects with it,” she says, stressing the importance of interactivity within the entirety of her practice, which is shaped by community and the unique outcomes of every joint experience she mediates. Every project develops twofold, including both a digital and a social game, to which players are invited to lend their voice, name or identity. By doing so, Brathwaite-Shirley ensures the audience feels truly invested in her art, and is willing to partake actively and meaningfully in the conversation stemming from it. She is outspokenly critical of passive art consumption, and bored of pieces that “wow” the public without challenging it. Art loses value over time, and meaning and resonance too, unless it elicits a degree of self-reflection when “it’s got your own name, talks about you and the decisions you make.”

The sociality of her work feeds on accountability and responsibility. Her practice centres the Black trans experience, and operates against its erasure and neglect via storytelling and archivization. The video games serve as a rendition of the latter—they represent Black trans people, document their lives and record their histories as a means of leaving markers in the present as references for the future. These are the terms and conditions of Brathwaite-Shirley’s practice, and the prerequisite to view and engage with her work. The actual games usually unravel in a quite unplanned and improvised way. At the Helsinki Biennial this year, she is staging a role-playing performance event where visitors are asked to embark on a pilgrimage; a journey through self-analysis and discovery fostered by collaborative decision-making. She will be orchestrating the game while remaining in the background and letting users’ choices determine its outcome, for “the main purpose is by the end they should be running it.” The whole point of what the artist does, she stresses, is facilitating a dialogue and a worthwhile exchange: “to generate opinions, entertain them and consider them through actions.”

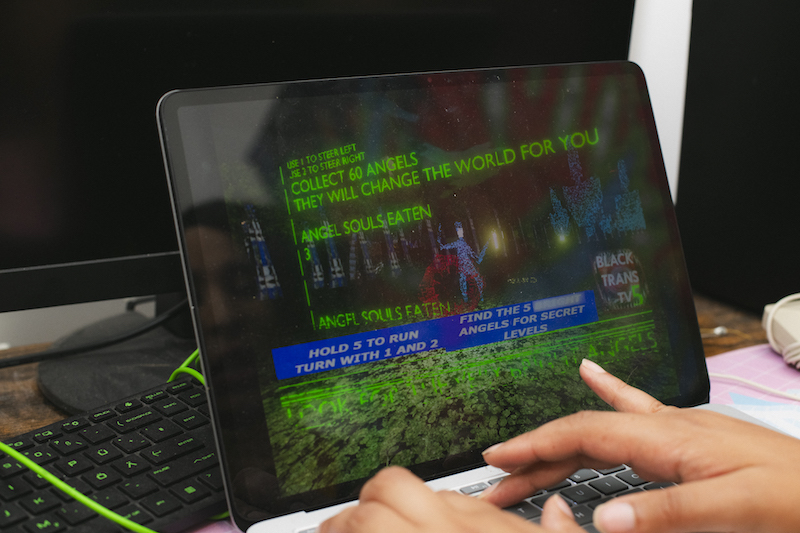

It takes a measure of selflessness to be able to make art and refrain from directing its reception. “Every time it’s a learning experience, it teaches me a lot about what people are likely to do, how people might interpret what you tell them,” she says, exposing a steadfast commitment to making her work accessible to everyone. Of course, Brathwaite-Shirley is still present in her own work, embedded in its very structure. She and the people in her life are the foundation of every immersive world she crafts; they constitute its textures, even though nobody is really able to see it. She shows me a video game whose interface weaves together images from her grandmother’s funeral: the very same church, clothes, flowers and grave feature in it. “Every texture has a purpose on why it’s actually in there, not just for texture reasons.” Every text does too, she adds. “These images are important to me, but don’t necessarily need to be the main focus of what I create.”

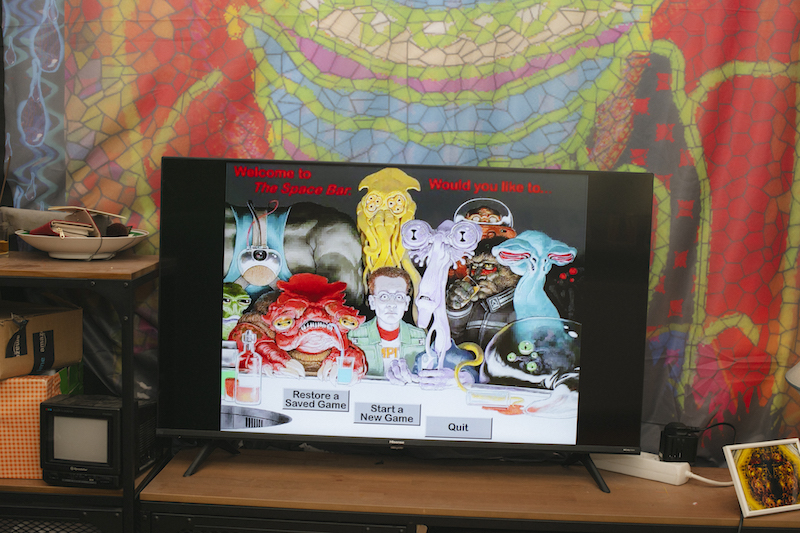

The movements are also taken from the real world: for the same game, she filmed two people for two hours and then took their motion and employed it using AI. A similar approach applies to sound design. For another film, all the voice acting and script was made over Zoom. “I gave people a scenario and asked them what they’d do over Zoom and then used what they said, editing the whole film around it.” If collaboration is a constant in her work, so are its nostalgic aesthetics. She likes old-style video games that aren’t highly rendered, soft and sleek, but “crunchy and strange” and have a textured feel to them. For her show in Dundee this year, ‘The Lack: I Knew Your Voice Before You Spoke,’ she made a game rendered at the resolution of Nintendo DS with small images of 256×256 pixels. For her next project, she will mix the DS look with that of PlayStation2. Overall, her style is informed by her painstaking research: “I’m a big nerd,” she jokes, when asked about her routine. She’s normally done with emails by noon, to then spend up to 10 hours daily at the computer rummaging through the archive.org, surveying hundreds of old games and drawing inspiration from them.

Brathwaite-Shirley makes everything herself in her studio. She works on multiple projects at once and it takes her, on average, about three months to put one together, and three more months prior to come up with a working idea. Recently, she’s branched out and teamed up with a sound designer, a conscious choice that somewhat affected her creative process. “It’s important to know what you want before you get people involved. They have their own practice that you need to respect, while allowing them to get on your wavelength and trusting them with the result.” From coding, through testing to performing, down to each game’s very texture, every segment of her work is the result of a collective endeavour and an attentive yet passionate exercise in mutual archiving. As part of her latest undertaking, she’ll release a free folder containing all the images, textures, sounds and text she has compiled. “I feel like I should give back,” she says, “so everything will be open source.” This is just one example of the early-internet era spirit of community that pervades Brathwaite-Shirley’s work, and an indication of the creative generosity running through her practice.