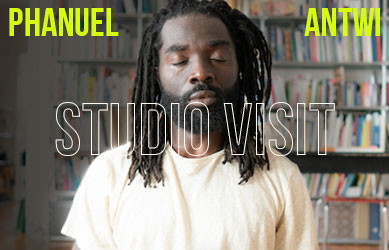

by Jayne Wilkinson, studio photos by Yuula Benivolski // Oct. 20, 2023

Whenever I visit John Monteith’s studio in Toronto, the first thing I’m always struck by is colour. He’s a fastidious colourist and his many series of abstractions are remarkable for their collective palettes. Recent works on paper, produced using coloured pencil on mylar transparencies, are hung across his studio walls at uniform height and size, highlighting their dynamic rhythms. His desktop is a rainbow of neatly organized pencils, markers, drafting tools. Among the most striking colour referents in his studio are tactile wool samples in every shade and combination, which he uses to produce commissioned rugs and weavings, and the new series of tufted-wool wall works he’s presenting at Toronto’s Hunt Gallery at the end of October.

His work explores expansive ideas about what drawing means, conceptually and literally, and suggests how repetitive mark-making in many media, including textiles, photography and video, can abstract what is inherently visible in the constructed world. In contrast to later work, his earliest drawings were figurative, a result of rigorous training in painting and drawing, and careful observation. During a previous studio visit, I was surprised as he pulled out several stunning, sensitive portraits, depictions of close friends rendered with dramatically assured linework. Surprised because, for much of his career, he’s experimented exclusively with abstract fluctuations in shape and colour. In many ways, he’s a modernist through and through, working in what he calls “referential abstraction”—a type of abstraction concerned with the observation and inclusion of real referents that are transformed through detailed, laborious work that disappears those same referents into abstract form. “Modernism was about denying an ideology of realism,” he tells me, “but for me it’s very much about identity, and about my own relationship to the built environment.”

Architecture is one of the most prominent influences in his work, the lines, shapes and grids of the modern city especially. His serial drawings take inspiration in global cities and aspects of memory and nostalgia that influence how we, individually and collectively, characterize our urban environments. New York, Berlin and Toronto are the cities he’s lived and worked in most, with time spent in Shanghai, Beijing, Kyoto, Taipei and London, and the influences of those cities overlap in ambiguous ways. “New York is additive, it’s vertical, at least that’s how it’s defined, it’s a city that grows upward. Berlin is like the opposite, it’s in the negative. When I was living there, it was very much a city of voids, of empty spaces and historical memory, a place to interject and imagine.” That interaction of positive and negative space plays out in the work: layered forms, transparencies and shapes relate to one another in vibrating compositions. Nothing is settled. There’s a restless rhythm that mimics the ever-changing nature of cities, even as his compositional structures are tight, flawless within each frame.

“Brutalism is an architecture of civic engagement, the architecture of universities, libraries, churches, court houses and civic institutions,” Monteith says. “Despite an often bunker-esque appearance, it’s a genre concerned with creating open, discursive spaces for the public; in contrast, we now have so many condos, bank buildings and corporate offices with these large transparent planes of glass, walled off, made entirely for private use.” We’re discussing a highly criticized plan to demolish a brutalist building designed by Raymond Moriyama—the much-loved Ontario Science Centre, which opened in 1969 to advance public education in the sciences—but the comment applies equally to many cities, where the familiar greens and blues of condo glass replicate themselves across city skylines.

When I meet Monteith in his studio, he’s finishing preparations for the Hunt Gallery exhibition, a collaborative project with sound artist and composer, Lou Sheppard. Titled ‘Signal to Noise,’ it will contain nine large textile works made of hand-tufted wool stretched over wooden frames and hung like paintings. As ever, an expanded definition of drawing-as-process is evident. The works originate with the tools of the architect (pencil, drafting transparencies, blueprints) and are translated through repeated individual acts of mark-making to become luminous, shimmering drawings that pull heavily from the shapes of the built environment. The drawings are then transformed again, enlarged in size and stitched into individual knots of wool.

As a material substrate, wool, with its warm textures and rough, imperfect qualities recalls the interiors of brutalist buildings, where corrugated concrete, natural wood and rich textiles are often used on the walls. Muted colours and uneven vertical lines (a relic of the tufting process) are tiny clues suggesting the surface is the verso of the weave, the side normally hidden from view. Monteith comments that while his drawings convey a cool opticality and operate somewhat like a façade, the weavings reveal imperfections and flaws—the fallibilities of the process are made visible.

A captivating part of this practice is how various influences hover just below the surface; another significant one is electronic music, particularly techno. Music defines the culture of a city, some more than others, and in the techno scenes of Berlin and house scenes of New York, London and Toronto, Monteith has forged many relationships and friendships, personal and professional. But he only started to consider this aspect of influence during the lockdowns of the pandemic when, alone in the studio for days and months on end, every aesthetic experience was heightened; he began to consider how the dimensional, spatial qualities of techno might influence how he intuitively works with form, even in two dimensions.

The collaboration with Lou Sheppard emerged after realizing their mutual shared interests in abstraction and modernist music composition—Brian Eno’s album Ambient 1: Music for Airports is one among many important works for them both, Iannis Xenakis and Le Corbusier’s collaboration another. Sheppard’s contribution to the exhibition is a nine-channel audio work created in direct conversation with the nine weavings. If the weavings gesture to the Brutalist buildings of mid-century, the sound work goes back much farther, almost gothic in its dissonance and cavernous in its syncopated sounds, suggesting an expansive environment that seems to develop vertically rather than horizontally. The audio adds another interpretation for the wall works: as functional acoustic sound panels that absorb and reflect the composition, they turn the gallery into a custom-designed space for listening.

After wrapping up in the studio, Monteith and I walk through the east-end Toronto neighborhood where his studio sits among a mix of old and new architecture: brick Victorian houses, soaring glass condos, postmodernist mid-rise co-ops, a block of mixed-use development that replaced a community of social housing, industrial and post-industrial lots. “I used to live here in the nineties,” he says, as we pass a former live/work studio building that housed a large community of artists and musicians. “Actually, everyone I knew from art school lived here at one point.” There’s a risk that comes from working in front of screens and growing accustomed to pandemic isolation, especially with so few physical spaces left for creative cross-pollination. It sounds cliché to say that the unexpected mixing of forms is what makes a city a city, which is why the sight of so many identical condos racing ever upward feels like a loss. Still, it’s heartening to consider that, even as cities change, what is erased or written over is somehow still embedded in the muscle memory of that place.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

Hunt Gallery

John Monteith and Lou Sheppard: ‘Signal to Noise’

Exhibition: Oct. 28–Dec. 2, 2023

huntgallery.info

1278 St. Clair Ave W Unit 8, Toronto, ON M6E 1B9, Canada, click here for map