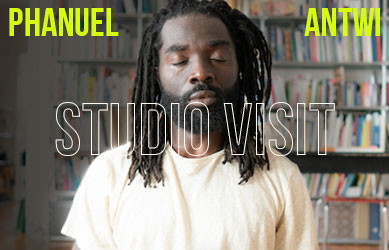

by William Kherbek // Nov. 24, 2023

This article is part of our feature topic Myth.

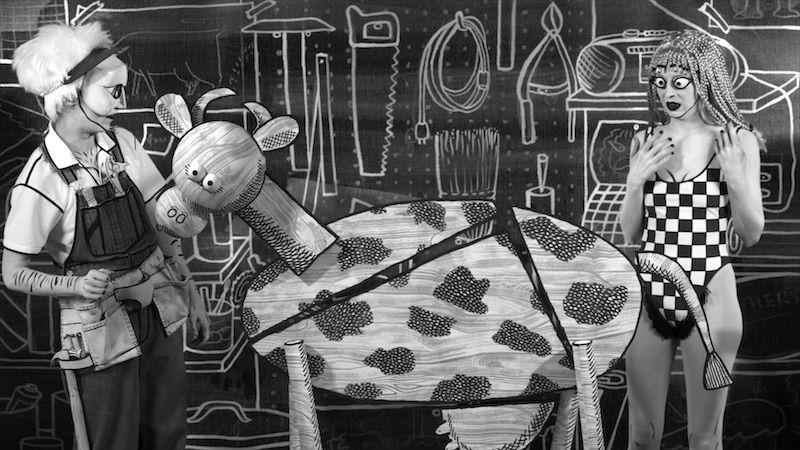

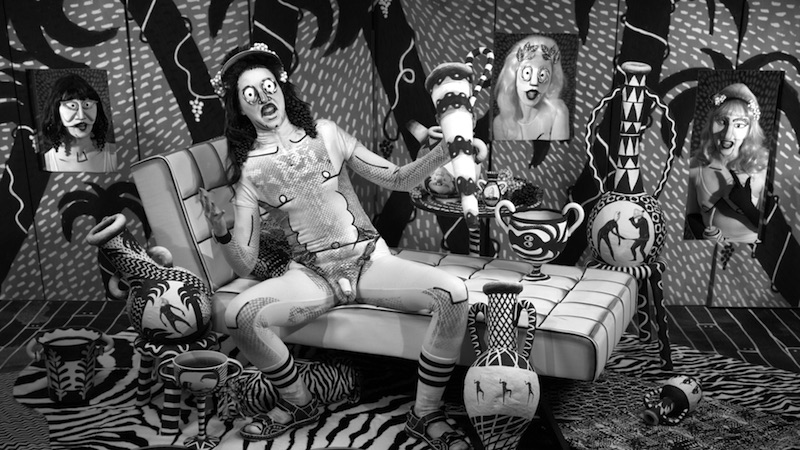

Mary Reid Kelley is an artist concerned with myths, both sacred and profane. The ‘Minotaur Trilogy’—consisting of the component films ‘Priapus Agonistes’ (2013), ‘Swinburne’s Pasiphae’ (2014) and ‘The Thong of Dionysus’ (2015) and realised in collaboration with her partner, Patrick Kelley—is their most sustained exploration of mythological themes; profoundly intertextual, the work draws on a range of artistic and poetic imaginings of the myth of the minotaur. The videos are rendered in stark black-and-white with imagery drawn from a range of visual sources, including Minoan pottery. The complex theatrical, cinematic and sonic landscapes they create involve elaborate linguistic narrations, as characters retell the myth of the doomed half-human, half-bull from a contemporary perspective. The density of references and registers are leavened with an anarchic flair for wordplay, and a sensibility that is more at home in a cabaret than in the pseudo-sacral spaces where the classical imaginary is encountered most commonly today. This demotic impulse enlivens these timeless stories, while also opening them up to critique and reinvention.

Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley: ‘Priapus Agonistes,’ 2013, HD video with sound, 15’9″ edition of 6 plus 2 artist’s proofs // Courtesy the artists and Pilar Corrias, London

William Kherbek: Could you speak to us about what got you interested in working with myths and mythologies?

Mary Reid Kelley: It’s been 10 years since we started the first of the ‘Minotaur Trilogy,’ and I feel that since then there has been a return on both of our parts to the idea of myth, but in a slightly different guise. Archetypes more generally have been on our minds for the past year. So it’s actually prompted some revision of why we chose that subject in the first place. I could maybe give you the answer I would have given you in 2013-15 when we were making the ‘Minotaur’ works but now I’m thinking of it in a different way. I think that artists choose myth as a kind of a pretext to escape their own personalities, and their own circumstances. The super dark sunglasses of your day-to-day life, myth might help you take those off. And when you jump into mythological work, especially something like the ‘Minotaur’ works, you’re immediately in this bacchanalia of other artists’ work, which is truly wonderful and inspiring. We gorged ourselves on the plays and the paintings and engravings, minotaurs, and labyrinths and everything.

Patrick Kelley: There was a sense of engaging something that feels authorless. There’s something kind of freeing [about myth] in that sense, which I think is why other artists engage with it: this authorless thing where you can’t find an origin.

MRK: Someone like Picasso worked with the minotaur for decades, but it’s not his invention. To pick it up now you pick it up for the same liberating reasons that any artist might: it’s not about you, in that moment. It frees you.

PK: One of the reasons to be drawn to it is the use of humour. There’s a humour in engaging something so archaic with a more or less contemporary voice, and that juxtaposition that occurs when you’re overlaying something that everyone has this archaic sensibility for, or some kind of overlap of understanding that people come with to these forms.

MRK: The essence of the minotaur, its archetype, to me, is that of rejection: powerful, powerful rejection. I think you can see that in Picasso’s etchings of the minotaur. They’re very sad. It’s a paradox: this powerful monster who is rejected, but for good reason! It will eat you!

Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley: ‘Swinburne’s Pasiphae,’ 2014, HD video, sound, 8’58” Edition of 6 plus 2 artist’s proofs // Courtesy the artists and Pilar Corrias, London

WK: Your myth-based works often have their own unique forms of language, often quite formal, which build on the ways in which language became a formal device for composing and transmitting myths. What were some of the considerations that came into your approach to using language in the works?

MRK: The feeling with mythology is that you’re liberated from the task of inventing everything. You don’t invent myth; you participate with it. You collaborate with the preexisting myth. You collaborate with the manifestation of the myth in different artists’ works. You discover along with everyone else who has done it over the centuries, what’s latent in the myth and what’s latent in you that connects to it.

That discovery over authorship does parallel my experience of writing wordplay and jokes and very often when I think of a wordplay or a joke, I google a version of it and see who else has discovered it, because you don’t invent a joke, you just discover it. Frequently, you see comedians accusing each other of stealing jokes—and I’m sure people do actually steal jokes—but it’s very possible just to discover things that are already there. Like Freud’s unconscious, archeologically-speaking. I think he used the city of Rome as his metaphor for the unconscious. In a mythological subject, you discover what’s already there. And I think there’s a similar process in writing wordplay. You just discover what’s latent in this natural abundance of synonyms.

Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley: ‘The Thong of Dionysus,’ 2015, HD video, sound 9’27” Edition of 6 plus 2 artist’s proofs // Courtesy the artists and Pilar Corrias, London

WK: Could you speak about the ways in which your approach to historical research versus research in relation to myth has developed? Myth and fact aren’t entirely opposites, but they’re certainly not synonymous. Perhaps the T.S. Eliot quotation from ‘Burnt Norton’ from the ‘Four Quartets’ touches on the need for myth in the conveyance of truth: “humankind cannot bear very much reality.” Having worked with historical subjects and mythic subjects for different works, how can the creative process lead to finding the space of truth that lies between facts?

PK: That made me think of how when we’re coming up with the kind of mise-en-scene of a shot, or the piece itself, we’re thinking about this realm of what would be thought of as a “fake fake.” The characters are on a set. We shoot everything on a green screen. Everything is fake, but the set itself we’re trying to make look like a theatre set, so it’s a clunky set. You have to suspend disbelief. I think that’s an analogous connection of avoiding reality, to convey what we want to convey, instead of shooting some kind of naturalist cinema. That wouldn’t work at all. It wouldn’t work with the language at all.

MRK: I love that line from Eliot. The beginning of the ‘Minotaur Trilogy’ is a parody of one of the Sweeney poems. I’m always turning to him for help. We’re working on a piece now about Marie Antoinette and that has a very historical aspect. We’re reading biographies, reading scholarship. The mythological research for the ‘Minotaur Trilogy’ was mainly engaging with artworks, but I think that they are the same in that they form, at bottom, a general pretext to get your limited intelligence, and your limited consciousness, your self-consciousness, over the barriers that it needs to surmount in order to drop into an archetypal stream, from which you then harvest what you need to harvest.

Again, it’s not really authorship. It’s just channeling and discovery. I think that does head-off falsehoods and lying, and it can prevent you from sounding like a dumbass or spreading misinformation. I think mainly it’s an emotional rinsing of the self. To circle back to TS Eliot, what he says in ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent,’ about the washing away of personality; art work isn’t a manifestation of the personality, but a suppression of it. I think that there’s something in the research process that launders the personality, and the intelligence of the encumbering author. You just drop into a channel, whether the channel is the minotaur or Marie Antoinette.

Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley: ‘The Thong of Dionysus,’ 2015, HD video, sound 9’27” Edition of 6 plus 2 artist’s proofs // Courtesy the artists and Pilar Corrias, London

WK: In the process of creating these works related to myth, there’s a critical dimension as well, challenging both the historical versions of myths and the archetypes they represent as well as the place and reverence for myths in “high culture.” Today, the rise of conspiracy theories could be a kind of manifestation of myth-making or collective authorship. I wonder if that’s been a phenomenon you’ve watched with a similar horror/fascination as me?

MRK: The way I think about it now, critique itself is an archetypal impulse that has its own contours: angry polemical dismantling or, conversely, building of narratives, like conspiracy theories.

This impulse to dismantle and rebuild and to reorder the shards of information is itself an archetypal impulse, a myth-making impulse. It’s not so much that I see, in contemporary theories, myth. It’s that I see the impulse to make conspiracy theories and narratives—which I share—as a mode. If you take the zodiac as 12 modes of teaching, or 12 modes of manifesting an archetype in the world, the conspiracy or dismantling critique taking-things-apart mode, belongs to Virgo, and that’s a mercurial archetype. It basically has to do with information. It’s more interested in the process of taking something apart and putting it back together than the morality of whether it’s right or wrong. It doesn’t care, it just does it. And everyone has some Virgo in them.

Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley: ‘Priapus Agonistes,’ 2013, HD video with sound, 15’9″ edition of 6 plus 2 artist’s proofs // Courtesy the artists and Pilar Corrias, London

WK: Could you speak about some of the ways in which you’ve sought to find new aspects of the myths you’ve worked with, and how you’ve sought to reimagine elements of these stories?

MRK: With the ‘Minotaur Trilogy,’ you could say that this myth is being critiqued because we have a female minotaur rather than the standard issue male minotaur. I feel like ‘The Thong of Dionysus’—that the whole project, really—was a pretext for me to write this scene where the minotaur is dead; she’s on the floor of the labyrinth, and Priapus—the hero who is kind of in the Theseus role—is looking for her, and he’s dying, too. He stumbles upon her dead body and he’s dying and lays down beside her, and the last thing he does before he dies is declare his love for her. Earlier, I was saying the minotaur is the symbol of rejection and the piece concludes, in part, with telling the dead and rejected minotaur that she’s loved, although in this very grotesque fashion.

Now, 10 years later, I think that that was the heart of the piece, this declaration of love, and this overcoming of death and rejection. I keep coming back to this idea of research as a pretext, or myth itself as pretext. I’m not denigrating either research or myth, because it’s our job as artists and writers to somehow find the pretext that will liberate what it is we actually have to declare. Research works. Myth works.