by Berlin Art Link // Dec. 1, 2023

This article is part of our feature topic Myth.

The current exhibition ‘HOPE’ at Museion in Bolzano—curated by Bart van der Heide and Leonie Radine in collaboration with DeForrest Brown, Jr.—merges science and fiction to envision hope beyond a human-centric view. Fusing topics from the fields of humanities, technology, ecology and economy across four floors of the museum, the group show asks: Where do we come from and where do we want to go?

On the second floor of the museum, an extensive archive honors Drexciya’s Afrofuturist myth of the ‘Black Atlantic,’ stemming from Brown’s deep dive into techno history for his book ‘Assembling a Black Counter Culture’ (2022). The influential work of the Detroit electronic music duo Drexciya imagines an underwater utopia populated by unborn children of pregnant African women thrown overboard during the Transatlantic Slave Trade. This mythic deep-sea civilization has inspired a wave of artists dealing with the intergenerational trauma of slavery by reimagining Black history. Techno album covers and paintings by AbuQadim Haqq, who provided visuals for Drexciya and many other Detroit musicians over the past three decades, are presented in the exhibition space alongside maps and timelines, while a story in sound unfolds through the speakers.

Brown is a musician, theorist, journalist and curator whose work explores the links between the Black experience in industrialized labor systems and Black innovation in electronic music. We reached out to him to learn more about his contribution and personal connection to the show, the myths surrounding the origins of techno as well as how Afrofuturist mythology relates to today’s society.

‘HOPE,’ exhibition views, Museion Bozen/Bolzano, 30.09.2023 – 25.02.2024 // Photo by Lineematiche – L. Guadagnini, © Museion

Berlin Art Link: Can you shed light on some lesser-known facts about the beginnings of techno music and how ‘Make Techno Black Again,’ your campaign that calls for the dismantling of the myths surrounding techno’s origins, came to be?

DeForrest Brown, Jr.: In the liner notes for the album ‘Retro Techno/Detroit Definitive,’ which compiled Detroit techno recordings from 1982-1988, Juan Atkins defined techno to be “music that sounds like technology” and further defined music as “sound painting.” ‘Make Techno Black Again’ came out of conversations with my partner and her friend who were both ravers in Berlin and Brooklyn about what techno would and could have sounded like, without Eurocentric drug and nightlife economies. The virality of rave culture through social media and Web2 platform capitalism was of interest to me, as one of the few African Americans working as an electronic music journalist in the early 2010s. Having held positions as an editor at Mixmag and freelanced for many other sites in the dance music world like Resident Advisor, Electronic Beats, and Red Bull Music Academy, I had seen much of the American EDM boom bust cycle from beginning to end, as well as the reaction and backlash from British and European club culture. I found it odd that there was no real discussion around how the emergence of Skrillex’s brand of Dubstep—“Brostep”—coincided with the 30th anniversary of the Fall of the Berlin Wall and the re-popularization of rave culture for a very online and global millennial generation.

‘HOPE,’ exhibition views, Museion Bozen/Bolzano, 30.09.2023 – 25.02.2024 // Photo by Lineematiche – L. Guadagnini, © Museion

BAL: The afrofuturist mythology created by Drexciya plays a key role in the current exhibition at Museion, as well as in your overall work. Can you talk about the significance, for you, of this mythology?

DBJ: Much like how Plato speculates on the existence and civics of the lost city of Atlantis in ‘The Republic,’ Drexciya exists as a speculative civilization materialized into our reality through the interaction of electronic instruments, music player devices and human hearing and imagination. Afrofuturism is an operating system for Black people to engineer a future beyond the capitalist colonial system we currently live in. Juan Atkins’ vision of techno pre-dates the coining of the term Afrofuturism by a decade, but also sets the precedent for a more colloquially applicable approach to Black science fiction beyond the aesthetic and more as a radical techno-political perspective.

‘HOPE,’ exhibition views, Museion Bozen/Bolzano, 30.09.2023 – 25.02.2024 // Photo by Lineematiche – L. Guadagnini, © Museion

BAL: What is your personal connection to the electronic music duo Drexciya and how does their legacy resonate with a broader audience today?

DBJ: I can really relate to their vision and intent as a Black person who grew up in similar circumstances, as well as in the aftermath of racial segregation and economic inequality. I understand why they would try to rewrite history and imagine something different than the oppressive reality we faced as African Americans coming from political backgrounds and circumstances. I’ve been in conversation with Gerald Donald, the surviving member of Drexciya, for quite some time, and wouldn’t make any decisions or comments on the mythology without having been immersed in his understanding of the science and technology of this speculative civilization and worldview. I’ve also talked at length with James Stinson’s widow about what he had intended when he and Gerald were creating this music and world. From what I understand, Stinson’s final recordings were released as he was relocating from Detroit to Atlanta. I grew up in Birmingham, Alabama, a still pretty segregated city where much of the Civil Rights movement was organized in conversation with Black communities in Atlanta and other cities in the Black Belt region—my grandmother worked at the jail where Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote his infamous open letter as a call for unity in 1963. While working with Bart von der Heide and Leonie Radine on the ‘Hope: Techno Humanities’ exhibition at Museion, I wanted to show how the myth-scientific aspects of Drexciya could be applicable in our postmodern, post-historical society. It was important to me that the exhibition worked within the sonic fictional environment of “the Grid,” which was first conceptualized by Juan Atkins and inherited and built upon by musicians like Drexciya and Underground Resistance.

‘HOPE,’ exhibition views, Museion Bozen/Bolzano, 30.09.2023 – 25.02.2024 // Photo by Lineematiche – L. Guadagnini, © Museion

BAL: At Museion, your book titled ‘Assembling a Black Counter Culture’ is partly translated into space. Can you elaborate on its key ideas and arguments featured in the exhibition and explain how they interrelate with the other elements on display—AbuQadim Haqq’s techno album covers and paintings, and the music playing from the speakers?

DBJ: I’ve been working with AbuQadim Haqq, who illustrated the album covers for Detroit techno and adjacent electronic music, for over three decades. I approached him in 2018 about illustrating the cover of my book ‘Assembling a Black Counter Culture,’ which appears in the exhibition and depicts an alternate future in the year 2100. My album ‘Techxodus’ continues our collaboration by exploring the combination of the terms “technology” and “exodus,” but means to give less importance to technology and focus more on the physical impact and effect that it can have on the mind and body, taking inspiration from Rayvon Fouche and Nettrice Gaskin’s concept of “techno-vernacular creativity.”

Haqq’s paintings act as portals that depict entire modal realistic worlds, decolonial incursions beyond human experience, fragmented within the space and format of vinyl records and CD covers. Displaying his artworks in chronological order, alongside a timeline and collection of albums seemed to be the best way to take the elements that served as a blueprint for my book and display it as an immersive environment called ‘Third Earth Archive.’ Within this space, over four hours of audio plays on loop crafting a sonic fiction made up of my album ‘Techxodus’ as well as two mixes, ‘The Myth of Drexciya’ and ‘Stereomodernism,’ which collects many Detroit techno and related Black electronic music across the diaspora.

‘HOPE,’ exhibition views, Museion Bozen/Bolzano, 30.09.2023 – 25.02.2024 // Photo by Lineematiche – L. Guadagnini, © Museion

BAL: How do you see this project relating to the exhibition’s overarching topic of hope?

DBJ: Hope appears firstly in the form of diplomacy and compromise between myself and the institutional framework of the Museion and its staff. As Afrofuturist Ytasha L. Womack explains in an accompanying text for the exhibition, the term and contemporary usage of hope exists in a similar manner as techno, originating in the modernist Black Civil Rights Movement as a call for society to imagine more than war and oppression. The Western world has failed to prove its worth as a civilization, and this is evident through the military domination, global boiling events and economic collapses that have come to define our contemporary post-capitalist future.

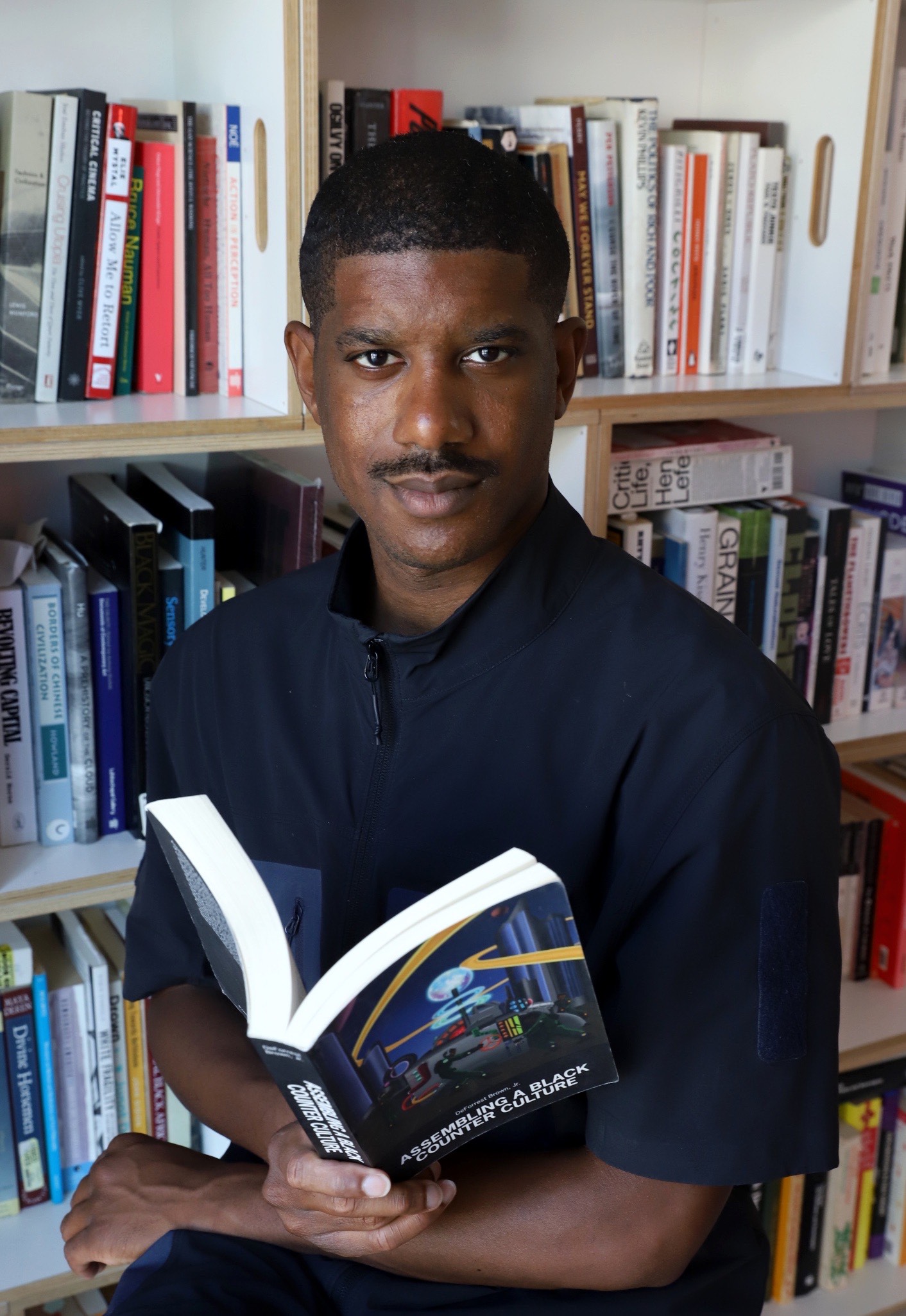

Portrait of DeForrest Brown Jr. // Photo by Ting Ding 丁汀

Exhibition Info

Museion

Group Show: ‘HOPE’

Exhibition: Sept. 30, 2023–Feb. 25, 2024

museion.it

Piazza Piero Siena, 1, 39100 Bolzano BZ, Italy, click here for map