by Juan José Santos Mateo // Feb. 2, 2024

This article is part of our feature topic Utopia.

Imagine a bright future. Global social uprisings have taken place and all of our wishes have come true. There is no need for political or critical art anymore, and artists are solely focused on creating pleasant, beautiful looking artworks. What would this actually look like?

The Spanish collective PSJM (Cynthia Viera and Pablo San José) fantasized about this utopia in their work ‘Shapes for a Perfect World’ (2017). But don’t be fooled, the ironic paradisiac projection is nothing other than a strategic way to raise awareness about the dangers of the present.

PSJM’s first attempt at envisioning a better tomorrow was with ‘Hydrogen Island’ (2010-2012), a novel and a utopian monument showing a mini energy plant with a garden and pond, where you could listen to music or get a tan from UVA rays. For the previously mentioned ‘Shapes for a Perfect World,’ they conceived works designed as if they were aesthetic objects made within an imaginary world, constructivist reliefs produced with traditional and weighty materials such as mahogany or bronze and stainless steel. In ‘CO2 emissions from 2020 to 2050’ (part of their series ‘Clean Future,’ 2021) PSJM prophesied a planet in which high CO2 emissions disappeared. This work is soon to be on view in the group show ‘Swerving the Apocalyptic Angle into Hope,’ curated by Stefano Cagol, at Glenda Cinquegrana in Milan.

Their early works were a fierce criticism of capitalism, enacted through irony and over-identification. However, in their latest projects, they have taken a step towards political management and activism. In ‘Symbiotic. Mobile Eco-Participatory Intervention Unit’ (2020-2022), ‘Neighborhood Identity’ (2022-2023) or ‘The Horizontal Hoya’ (2018), for example, they have achieved something utopian: that a disjointed community could merge and accomplish things like repairing a city wall. PSJM create lasting bonds with residents of parts of the Canary Islands through participatory actions, in which neighbors diagnose, decide and execute the project. We spoke to the duo about how their work is entangled with the notion of utopia, both in the content and aesthetic of their museum-ready art objects and in the process and methodology they use to enact their more socially-engaged or activist works.

PSJM: ‘Symbiotica. Mobile Eco-Participatory Intervention Unit,’ 2020-2022, with Rita Rodríguez, Mireia Tramunt, Asiria Álvarez, Sara Rodríguez, Irene León and participants // Courtesy of the artists

Juan José Santos Mateo: You began your career with critical works focused on capitalism and corporations and gradually drifted towards activism, management and community-oriented practices. Have you become less incisive and more pragmatic? Are you less artists and more political agents?

PSJM: In her ‘Trojan Horses: Activist Art and Power,’ Lucy Lippard distinguished between political art—that which is concerned with the issues—and activist art, that which is involved in them. That is to say, the first thematizes politics and the second practices politics. It is true that we are now involved with activist art projects, but we also continue to make political art, that is, art that deals with political issues and that is part of the field of museums and galleries. The entire procedure of “social geometry,” through which minimalist works are generated based on statistical data, is part of that area of criticism within the institution that thematizes a political agenda.

In that sense, we continue to defend the thesis that we promulgated in our book ‘Friendly Fire’ (2014): “act with all the tactics and strategies at your disposal in all available areas.” By getting involved and intervening directly in society with community practices, we have expanded the pragmatic scope of our actions, but we have not stopped being incisive, since we continue to do critical work within the art institution and, on the other hand, many of the participatory projects also have a strong protest character.

As for the second part of your question: no, we have not stopped being artists or become less artists. In fact, we follow an old avant-garde tradition linked to the LEF [Soviet arts journal], which, for example, understood a demonstration as an artistic action. “The streets are our brushes, the squares our palettes,” said [Vladimir] Mayakovsky. Any activist art practice of intervention in public space maintains this tradition and is thus an artistic practice like any other. Furthermore, a feature that distinguishes our participatory work is that we strive to make the pieces work both in the neighborhood and in the museum. We always worry that the product of collective action can be “museable.” From the beginning, we have been moving in and out of the institution, placing objects and disciplines inside and taking the institution outside.

PSJM: ‘Symbiotica. Mobile Eco-Participatory Intervention Unit,’ 2020-2022, with Rita Rodríguez, Mireia Tramunt, Asiria Álvarez, Sara Rodríguez, Irene León and participants // Courtesy of the artists

JJSM: Perhaps the first work in which you openly think about utopia is ‘Hydrogen Island,’ wherein you imagine a future with no artists, but rather designers of experiences. Looking back, is reality going in the direction you imagined, or on the contrary, are we further away from your hopeful ideas?

PSJM: Things don’t look good, it’s clear. The military escalations, the dominance of the global extreme right and a climate emergency that leaves us on the verge of the sixth extinction, do not seem to want to show a world that comes even remotely close to any utopia, and even less to one based on empathy. In any case, the function of utopias is not to predict the future, but to set guidelines to follow so that this does not derail completely.

PSJM: ‘The Hydrogen Island,’ 2010, project illustration // Courtesy of the artists

JJSM: In ‘Shapes for a Perfect World,’ you speculate about that better future by—as in ‘Hydrogen Island’—fusing literature, sculpture and design. One of the things that brings me the most optimism about this work is that you can not only dream of utopia, but also, if you get there, by following your idea, the need to create art will remain (unlike in ‘Hydrogen Island.’)

PSJM: Well, in ‘Hydrogen Island’ the “need to create” was maintained, that is a human condition that cannot be suppressed, another different issue is the need to create “art” and what we call art. There we imagined a world in which creators generated objects, spaces and situations intended to provide an aesthetic and intellectual experience without these objects, spaces and situations being subject to the laws of the market, speculation, exclusivity, luxury and social exclusion. In short, “experience designs” were, if you like, “social art.” In ‘Shapes for a Perfect World’ the focus of enjoyment moves from the user of those experiences, to the producer of them. It’s about the pleasure of creating.

In reality, the project is nothing more than an excuse to create the type of work that we would like to do, without further ado. We would love to get up in the morning and get to work in the studio to simply make beautiful shapes, harmonious geometries, but reality, the social situation, the climate emergency, does not allow us to do such a thing. Along with the need to create, the need to transform, to fight for justice, acts with equal force. We have reflected on these issues in our article ‘The Aesthetic Imperative’, in which we related this to the ethical imperative. On the other hand, the appearance of ‘Shapes for a Perfect World’ refers back to the era of constructivism. Rogelio López Cuenca, when he stood before these works, said: “they seem real,” that is, taken from that time. The time of utopias, of great projects. Without a doubt, ‘Shapes for a Perfect World’ also affects the failure of those modern Promethean projects. It would seem that we can only understand utopia, ironically, by looking at the past. Now, after postmodernity, in the era of platform capitalism and the climate emergency, utopia is different.

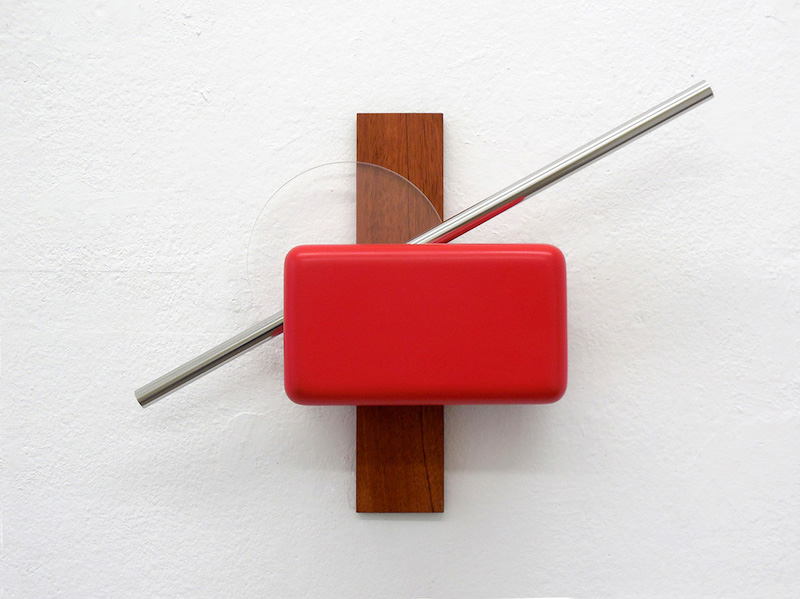

PSJM: ‘Shapes for a Perfect World. Shape 2,’ 2017, mahogany, steel, acrylic glass, painted and polished MDM

32 x 50 x 11,6 cm // Courtesy of the artists

PSJM: ‘Shapes for a Perfect World. Shape 1,’ 2017, mahogany, steel, bronze, 61 x 23 x 17 cm // Courtesy of the artists

JJSM: In your ‘Clean Future’ series you operate with a type of achievable utopia.

PSJM: It is a utopia of survival. For example, in the painting ‘CO2 emissions from 2020 to 2050,’ a graph based on predictive data indicates that emissions will disappear in 2050. A perhaps utopian future is shown, but if utopia always describes a perfect world, which must be achieved to mitigate the evils of the earth, in this case that happy goal must be achieved, not to perfect but to survive. Without utopia, in this case, there will not be a worse world, there will simply be no world to live in.

PSJM: ‘CO2 Emissions from 2020 to 2050 (cement, buildings, industry, transport, energy industry, electricity),’ 2022, ecological acrylic lacquer on canvas, 70 x 70 cm // Courtesy of the artists

JJSM: In more recent collective actions, such as ‘Symbiotic. Mobile Eco-Participatory Intervention Unit,’ ‘Neighborhood Identity’ or ‘The Horizontal Hoya,’ you already stop imagining and move decisively to try to carry out real micro-utopias. Considering the differences in ideology, origin and individual reality of each neighbor with whom you carry out the initiatives, is it easy to get an entire group of people to envision the same idea of utopia?

PSJM: No, it isn’t. It’s very hard. But that’s not exactly the purpose either. The various people participate in the project for a shared interest, which may be the naturalization of the neighborhood, the creation of common identity symbols or the fight to improve their living conditions, for example. Around this common objective, what is put into motion are democratic forms of creation and production. This is where micro-utopias are produced, acting in small laboratories of social and artistic innovation. The books we write, whether narrative (‘Hydrogen Island’) or essayistic (‘Art and Democratic Processes’) serve as a guide to lay the theoretical foundations. Our productive process consists of theorizing the practice and guiding it with the theory to then reflect again on the practice in the written medium and thus, in a feedback loop, try to correct the theory with practice and practice with the theory.

In ‘Art and Democratic Processes’ we analyzed the processes of participatory art based on the three categories of socialization of [Jürgen] Habermas: labour, language and power. When applying this scheme to our field of study, we find that each of these categories contains an ideal model-form: the working model is found in cooperation, the ideal type of communicative interaction would be deliberation and power is understood as empowerment or a horizontal power relationship. These three ideal axes, when they come up against human material reality and its cultural inertia, generate at least three dualities in tension: cooperation versus competition, deliberation versus negotiation, and empowerment (horizontal) versus authority (vertical). In the assemblies and workshops with neighbors, these tensions are managed in order to get closer to the ideal forms (or utopian, if you like) that we proposed as a guide in our theory: horizontal power relations, generalized deliberation and cooperation in search of a work well done.

PSJM and AC/AV: ‘Hoya de la Plata Original,’ 2019, La Hoya Original, Action 4, neighborhood performances, participatory process // Courtesy of the artists

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

Glenda Cinquegrana Art Consulting

Group Show: ‘Swerving the Apocalyptic Angle into Hope’

Exhibition: Feb. 13–Mar. 30, 2024

Opening Reception: Tuesday, Feb. 13; 6:30pm

glendacinquegrana.com

Via Luigi Settembrini, 17, 20124 Milano MI, Italy, click here for map