by Aurola Győrfy, studio photos by Benjamin Busch // Mar. 28, 2024

Can we compose together, or is it a solitary act? When we decide to have a rehearsal, we already take the first steps toward a collective process. Exploring the intersections of composition and community and re-imagining the sound of collaboration in his practice, Ari Benjamin Meyers first develops his projects in his studio, located in a quiet part of Kreuzberg. The surrounding buildings shield the studio from the sounds of the street, making it the perfect place for Meyers to rehearse, compose and write. In the bright room, the piano takes center stage. As we sit down on the sofa opposite the piano, he tells us about the building, which used to be a factory for making safes, and now houses a film production company as well as several artist and photography studios.

Meyers, an American composer and artist hailing from New York, has been based in Berlin for nearly 30 years. His work explores the ephemeral nature of sound and music, while redefining notions of collaboration and performativity, shifting the classical concert experiences into communal rituals. In particular, Meyers’ recent works—‘Forecast (LX23)’ and ‘UNLESS’ (2023)—are focused on climate crisis and urgent ways of reconnecting with nature and relocating ourselves in our environment.

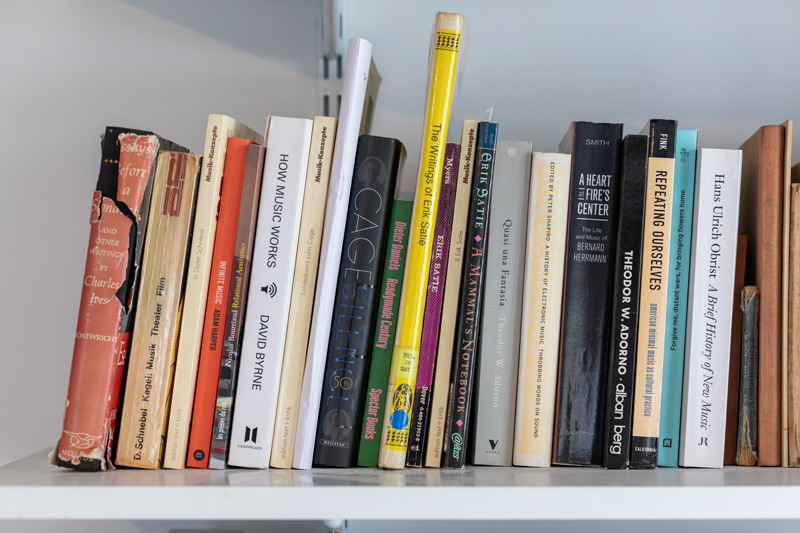

In his studio, we talked about our earliest memories of live music: his father was a jazz musician, so “there was always music in the house,” he tells us, revisiting the image of the piano in the living room of his family home and how he was drawn to play it at a young age. The piano in his current studio is one of the most important stations in it—during his work, Meyers moves from the piano to the writing desk, eventually opting to clear his head and consider the projects in a less tangible form on the couch. One of Meyers’ most constructive and memorable meetings with sound as a kid, he tells us, was when he saw the 1984 Talking Heads concert film ‘Stop Making Sense’ in a cinema. But he also recalls the influence of Leonard Bernstein (whom he later came to know personally) throughout his childhood. Both examples, though disparate in many ways, foreshadow his interest in transforming spaces into immersive musical worlds.

Meyers has worked in opera and experimental theatres, as well as organized projects with his “club orchestra,” and often creates exhibition-like spaces for experiencing sound and music. The seamless movement between conducting and composing, and experimental forms of collaboration allows him to discover and overlap different forms of musical self-expression in constant oscillation. He describes the rapid switch from one extreme to another as a bit like schizophrenia: Meyers studied classical music while playing in rock bands, and was always looking to find a way to create a dialogue between the more experimental music that he loved with the classical composers he was studying. His current role as an artist allows him to metaphorically shift between these areas with complete flexibility. “Moving in the direction of art was all about freedom,” he says.

I ask about the poster on the wall of Meyers’ studio that reads “The Name of This Band is The Art,” echoing a Talking Heads album title with a similar name. It was created for a project he’s revisited over the years, in which he exhibits a temporary rock band, a manufactured group whose members—made up of art school students who responded to an ad, in which the terms of the band’s existence are already set—are destined to play together only for duration of the show. The work follows the band from its first meeting, through the first rehearsals, to becoming a group, and, inevitably, breaking up—all of which takes place within the gallery. While the break-up is a pre-requisite of the piece, the process of collaboration—the work of becoming a band itself and the inevitable fleeting connections made by its members—is laid bare in the work, providing insights into some of the key elements of Meyers’ practice.

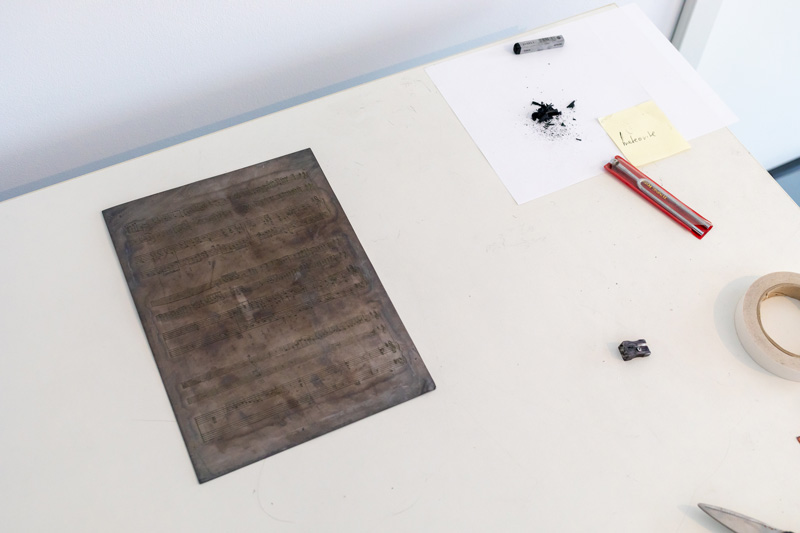

The act of getting together and practicing was also the focus of Meyers’ project ‘Rehearsing Philadelphia,’ which began in 2022 and brought experimental musical performances to public spaces: solos, interactive duets, ensembles and orchestra performances all focused on showcasing the process of rehearsal and the collaborative social power of music-making. In classical music, the role of rehearsal is a background process of perfection, which is necessary for the precision of the real performance—an invisible and hidden collaborative practice that overshadows the significance of coincidences and improvisation. ‘Rehearsing Philadelphia,’ however, foregrounds the process itself, legitimizing rehearsal as a community-building and shaping act. With changes in recording capabilities, the nature of music has also been entirely altered, and it’s something that we often take for granted. “Making music has been always a social act,” Meyers reminds us. As much as his studio is space for thinking through his projects, it’s also a place of collaboration. In a soundproof back room, equipped with instruments and microphones, he often rehearses with musicians and artists from different fields (visual artists, performers or filmmakers), finding a common language.

As an artist who is interested in exploring new strategies for the reception of music in spaces of contemporary art, a cornerstone of Meyers’ practice, for me, is his project ‘Kunsthalle for Music,’ a nomadic institution that reflects on the question of how can we redefine the classical concert format. ‘Kunsthalle for Music’—which will be making its museum debut (it has already appeared internationally in other types of art spaces) at the Museum Abteiberg in Mönchengladbach this spring—is a live exhibition, in which an ensemble performs a site-specific, choreographed musical score, drawn from an ever-growing collection or repertoire, known as the Songbook. In it, more than 40 selected pieces (and counting) by artists and composers, as well as some of Meyers’ own pieces, are archived. The work asks: are there other ways of experiencing live music? What formats might expand the listener’s freedom of movement and decision-making?

In a similar way, the liminal space between the classical concert experience and club night was brought to life in one of Meyers’ earlier projects with his 17-piece ‘club orchestra’—Redux Orchestra—which took place at Berlin’s nightclub Watergate between 2005–08. With the orchestra, he created live remixes of music by a variety of artists, from American minimalist composers to EDM producers. Meyers views the club setting as a hyper-theatrical space: we enter the club-like characters in a play, transforming into alternative personas with costumes and makeup. Our participation in the night is decoded not primarily through a system of speech and language, but through music, movement and ecstatic dance.

More recently, Meyers has been exploring encounters with sound and music in nature, through site-specific pieces that depict the experience of grief brought on by the collective trauma of climate change. ‘Forecast (LX23),’ looking closely at the phenomenon of weather and prediction, explores the insatiable and deconstructive human need to dominate nature. The piece also commemorates the American lawyer David Buckel, who committed suicide by self-immolation in New York in 2018, as a protest against the fossil fuel industry. One of the most memorable lines of the piece, for me, is the assertion that “a tree falling in a forest without anyone to hear it does make a sound.” The seemingly innocuous statement hammers home the fact that, if no one listens to the orchestra of nature, the diverse voices emanating from it will eventually become extinct. It’s a re-contextualization of the set-in-stone first rule of music theory, raising the question: Can something exist without being perceived by our consciousness? What does music mean if there is no one to hear it? The underlying theme of collaboration, and the ways in which Meyers’ practice exposes its inner-workings, might plant the seeds of a model for how we can approach other more difficult issues—a kind of activism, or at least a coming together that music can facilitate. In this vein, one of the early performances of ‘Forecast’ at Volksbühne ended with a public, collective rehearsal. “This is the beginning of action,” Meyers says.

Artist Info

aribenjaminmeyers.com

estherschipper.com

Exhibition Info

Fondazione In Between Art Film

Group Show: ‘Nebula’

Exhibition: Apr. 17–Nov. 24, 2024

inbetweenartfilm.com

Via dei Tre Orologi, 6, 00197 Roma RM, Italy, click here for map

Museum Abteiberg

Ari Benjamin Meyers: ‘Kunsthalle for Music in Mönchengladbach: Act II’

Exhibition: May 5–June 23, 2024

Opening Reception: Sunday, May 5; 3pm

museum-abteiberg.de

Abteistraße 27, 41061 Mönchengladbach, click here for map

Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne

Ari Benjamin Meyers: ‘Forecast (LX23)’

Performance: June 12–13, 2024

vidy.ch

Av. Emile-Henri-Jaques-Dalcroze 5, 1007 Lausanne, Switzerland, click here for map