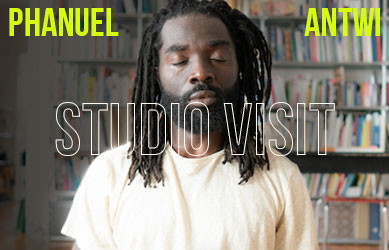

by Dagmara Genda, studio photos by Ériver Hijano // Apr. 11, 2024

The fine art landscape tradition is admittedly not the first place I would position Trevor Paglen, who is a writer and activist in addition to being an artist, and whose aesthetics tend toward espionage and surveillance rather than pastoral views. His now famous photographs of CIA military bases, for example, are blurry representations of classified sites, taken, as they are, at a five mile distance in the distorting heat of the Nevada desert. But, as Paglen explains during a visit to his Berlin studio, it was the landscape tradition that led him to seek out hidden environs and to complete a doctorate in Geography in the first place: “I wanted to understand landscape in a more nuanced and polyvalent way.” This nuance manifests in images of places that are rarely seen, and often not meant to be seen, as opposed to pictures of natural environments colonised by the conventions of depiction. Though, in its relation to power, Paglen’s work does find a place in the larger landscape tradition, which, as noted by art historian W.J.T. Mitchell, is a “particular historical formation associated with European imperialism.”

Imperial logic weaves through Paglen’s research into government deception programs, known as PSYOPS, or “psychological operations.” In a text accompanying ‘You’ve Just Been Fucked by PSYOPS,’ his 2023 solo show at Pace in New York City, Paglen writes “PSYOPS are designed to make people see what you want them to see, perceive what you want them to perceive.” Originally designed as a form of deceptive, psychological warfare, as with the “Ghost Army” of painters, designers and architects during WWII, PSYOPS are now fair game in the world of commerce, threading their way through AI and algorithm-supported media and communication technology. We are racing “into an era of ‘PSYOPS Capitalism,’” writes Paglen.

As our conversation in the studio turns toward an article Paglen is currently working on, the atmosphere starts to mirror the tone of discussion. The artist’s workspace itself feels like a secret site. It’s a renovated red-brick carriage house hidden in the back courtyard of an old Kreuzberg apartment building—a picturesque turn-of-the-century oasis nestled between drab, plastered walls. The production area, where we are sitting in black office swivel chairs, is an immaculate, grey-walled room filled with monitors and computers. A whiteboard bears cryptic remnants of a brainstorming session, the back wall is papered with photographs, print-outs and notes, one desk is covered by a large cutting board and equipped with drawing tools. There is nothing “artistic” about this studio; it could just as well be an office for investigative journalists or a working space for game designers.

Meanwhile, Paglen is explaining the connection between PSYOPS and past CIA mind control experiments like the famous MKULTRA. The logic that led the U.S. government to perform illegal LSD testing on unsuspecting people in the hopes of reprogramming human consciousness is, he asserts, the same logic used in TikTok and other increasingly AI-steered social media. “You can think of something like TikTok as being an influence operation, a media form that is designed to create a particular reality for you, that will be different than the one created for me,” he explains. When I ask about his take on the government’s move to ban the app, he weighs his words carefully, presumably knowing that in a smartphone-addicted world, his position might sound alarmist, technophobic or, worse, like a conspiracy theory. “I don’t want to go down the rabbit hole of that particular policy solution and whether it is the correct one,” he says and then takes a deep breath, “but there is a problem with [social media] that is much worse than generally accepted. I think that we need to start thinking about the media environments that we are creating and living in as an emerging health crisis of our collective brains.”

Avoiding data collection and the effects thereof, admits Paglen, is impossible, though the theme of privacy appears throughout his practice. Upstairs a circuit board stands on a plinth—it’s a “sculpture” that produces a secure internet connection and was once installed at KW in Berlin. Not only could users securely connect to the web while visiting the museum, but people from all over the world could take on the identity of the museum when online. Paglen spins in his chair to point to a computer that is never connected to the internet. “That’s where we work on sensitive projects.” Other security protocols include data encryption, secure web browsers as well as secure operating systems. In his private life, he will look up health issues on secure browsers, so that insurance companies cannot arbitrarily up his rates.

Software development for each project is also partly a security issue, though each piece of software is embedded into its project’s concept and is a stamp of artistic integrity. He motions to the desk where the software developers write the code that will become an artwork: “Formally and conceptually, that is something that I always strive for, to make things that are not so much about something, as much as they are that thing, or embody that idea.”

One such work is ‘Faces of ImageNet’ (2022), which is currently on show at KW’s ‘Poetics of Encryption’ and from which a dataset sample is printed and framed at the entrance door of the studio. The piece revealed the biases encoded in ImageNet, an online image dataset run by researchers from Stanford and Princeton universities, which was and remains a training set for AI recognition technology. Ever since Paglen trained his own AI on their data to show how people could automatically be labelled as “alcoholics,” “convicts” or “first-time offenders,” among other yet more derogatory terms, ImageNet has taken the offending material offline. And while these particular categories aren’t in use by ImageNet anymore, they are “still built into a lot of production systems,” warns Paglen. “One of the problems with AI is that you do not know where these datasets end up.”

Though only two years old, the training-set approach is already outdated in the artist’s practice. “Back then, that was still an interesting question. What training data do you use? How do you use it to make art?” says Paglen. Now, in preparation for an upcoming show in San Francisco, he and his team are developing new work where AI plays an invisible role, much like it does in our daily lives. Topics addressed will include mind control, UFOs, and, adds the artist with a smile, “magic will weirdly be a big part of this.” The goal is to “come up with a series of visions of worlds in which it is taken for granted that nothing is real and yet our minds are still sculpted by the unrealities that are continuously curated for us.”

When Paglen shows me his work ‘Fanon’ (2017), a large print hanging at the staircase landing on the first floor, it occurs to me that he not only pictures landscapes in his work, but materialises human beings as a type of landscape as well. ‘Fanon’ is what is called a “faceprint.” A computer was trained on many images of Frantz Fanon’s face in order to be able to reproduce or “recall” it, via a dispersal of visual elements, in this case pixels, based on probability. Presumably because images in the training set were of varying qualities, taken at varying angles and at various times of Fanon’s life, the portrait ends up being a blurred, ghostly semblance of the original person. This faceprint is in effect a map, or even a blueprint, which renders humans into a type of landscape for the machine eye. Mitchell argues that landscape should be understood not as a genre, but as a medium used to express value as well as a mode of communication, specifically between the human and non-human. In this case it would follow that humans are becoming the medium of machines. We are their Other, tamed into landscape, rendered into data that can be, according to algorithmic values, manipulated and deformed.

This process has very real consequences for society and for how we, as humans, perceive ourselves. Landscape requires a specific, cultured gaze to view—a gaze that becomes “naturalised” via the status of its subject matter as something beyond the human. It thus presents itself as a type of objective truth, functioning as an invisible frame that shapes what we see. Instead of a living ecosystem, we see territory, real estate or a site of extraction. With AI, this happens on an individual level. It naturalises the gaze of the machine, which is seen as emotionless, Other, potentially objective given a dataset that is big enough. When this gaze is applied to human beings, they become nothing more than data and sites of extraction, and yet this is enough to produce powerful results that in turn can change people’s views on free will, self-determination as well as democracy.

Paglen has often said that he wants art to not only “help us see the historical moment in which we are living,” but to also give us a glimpse into alternate futures, a prospect that seems less and less likely as our conversation progresses. When I ask if there is a way to envision futures outside these false realities, he becomes reflective, swivels slightly in his office chair. “I wonder if this question of imagination suddenly becomes more important? Our media environment is increasingly generated for us by machines and what machines cannot do is jump out of their own training data. They are not able to imagine different worlds. So much of what we might call “progress,” in regards to queer rights, feminism or political projects that have tried to extend representation to larger and larger groups of people, are hugely imaginative projects. They are trying to imagine a different conception of what it means to be human or what it means to be a political subject…To me that seems like the kind of thing that an algorithmic media environment cannot do.”

And yet, I am left to wonder how good humans are at looking beyond the frame. Is it even possible to do so? This is what I think Paglen points to in his strangely mute pictures of classified landscapes. They intimate a reality to which we have no access and perhaps never will. They only insinuate the frame, but by doing so they grasp at that unarticulated unknown—a reminder that there is a way out, even if we can’t reach it just yet.

Artist Info

Exhibition Info

KW Institute for Contemporary Art

Group Show: ‘Poetics of Encryption’

Exhibition: Feb. 17–May 26, 2024

kw-berlin.de

Auguststraße 69, 10117 Berlin, click here for map