by Ananyaa Sathyanarayana // June 7, 2024

This article is part of our feature topic Habitat.

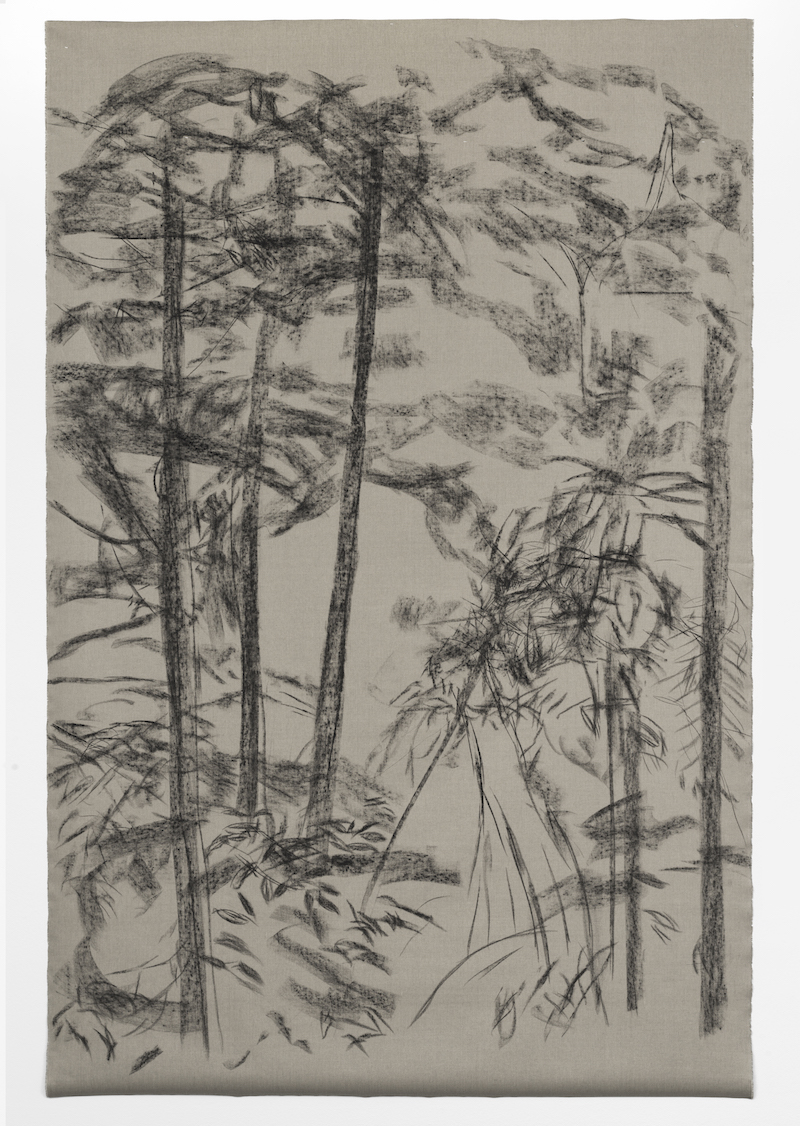

Mitte gallery Dittrich & Schlechtriem is currently showcasing works by American artist and conservationist, Haley Mellin. Mellin uses a variety of media in her works, sourcing those with non-toxic properties such gouache and charcoal and sometimes even coffee, in order to highlight her commitment to environmental justice and the conservation and sustainable evolution of diverse ecosystems. Her current exhibition, ‘Biodiversity and Betadiversity’ features a series of photorealistic paintings of arboraceous landscapes in countries such as Guatemala, as well as observational yet loose charcoal drawings reminiscent of Chinese handscrolls in their vertical structure and stylized line work. In a recently published letter to Nigerian-American writer, curator, theorist and facilitator, Enuma Okoro, Mellin writes: “Nature is somewhat of an enigma, there is so much unknown, so much mystery. Despite all our technologies and all our knowing, we still have only described (“known/recognized”) one out of eight living species, so it is thought. When one draws, one marks the passage of time.”

In 2017, Mellin founded Art into Acres—a nonprofit organization with the mission to promote engagement with local cultures in order to bring marginalized voices and artists to the forefront by taking action in regards to urgent environmental concerns. The foundation also underlines the importance of contemporary art and the art world’s impact on the environment. The exhibition at Dittrich & Schlechtriem delves into the notions of “legacy” and “permanence” by portraying preserved ecosystems through diverse conceptual lenses within the gallery space. We spoke to Mellin about the importance of integrating conservation into both the content and the concept of her work, and what we as humans can learn from attuning to the natural habitat we share with other species.

Haley Mellin: ‘Biodiversity and Betadiversity,’ 2024, exhibition view, DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM // © the artist, courtesy DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM, Berlin, 2024, photo by Jens Ziehe

Ananyaa Sathyanarayana: Your exhibition at Dittrich & Schlechtriem features paintings and drawings of old-growth landscapes. What is your aim in depicting these environments?

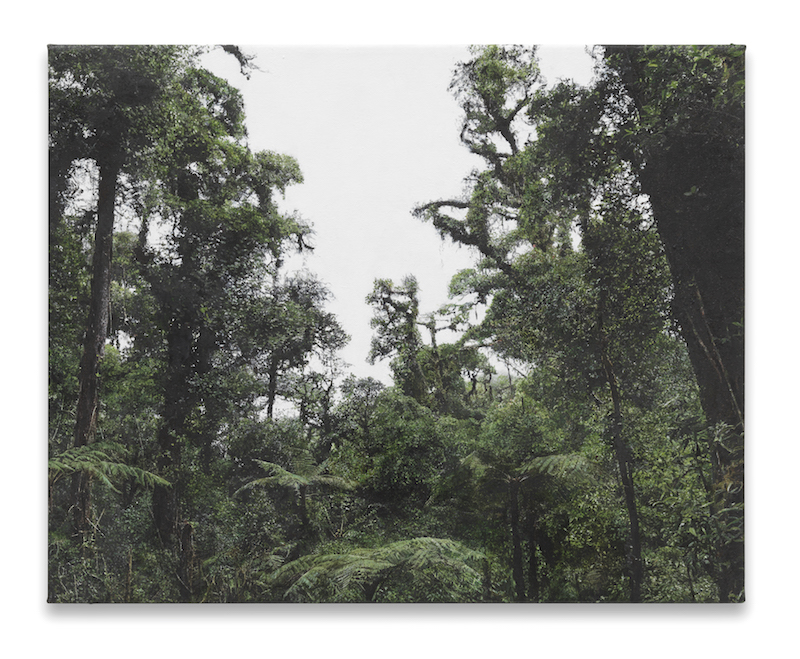

Haley Mellin: The paintings are of habitat—the homes of many, many species. The planet is not solely for us. There are about 8.7 million species, and the “canvas of land and water” is the basis of the “painting of life.” Habitat is a necessary ingredient for species to live and evolve, we all need a space to be. My paintings aim to be a gentle reminder that we are not superior, that all species share land and that we are not alone.

Haley Mellin: ‘Northern Highlands, Guatemala,’ 2024, gouache, acrylic, charcoal, and ink on canvas, 40.64 x 50.8 x 3.17 cm // Courtesy of DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM, Berlin, photo by Jens Ziehe

AS: The exhibition is titled ‘Biodiversity and Betadiversity,’ suggesting a nuanced understanding of the importance of diversity within ecosystems. Can you tell us about the meaning of the title and why you want to create the distinction between the two terms?

HM: Biodiversity is a shortened term for the words Biological Diversity—meaning the diversity of life. It signifies the vast, complex and intricate nature of the living ecosystems on this planet. It also signifies time, as time is an inherent ingredient in the complex development of life. Evolutionarily, the web of life is very much that: a web. The web’s structure and reinforced strength comes from the interactions between many species, and the intersections of the web represent the reliance between species. For example, a bird eats a frog, that eats a fly. Also, for example, a frog hides from the bird, in a burrow, created by a burrowing snake. As such, the web of life is a representation of our interconnectedness. Species are not independent of our reliance on one another. All species, taken in concert, together, make the possibility for life on this planet.

Betadiversity is a term that is defined as complex biodiversity. Imagine eight web-of-life’s stacked on top of each other. This refers to places on Earth where there is an abundance of many, many species that can play the role of one another. There is a redundancy of support, a redundancy of diversity, so that if a species is not present, another takes up the job of keeping that point in the web strong and intact. Betadiversity shows complex life in exceptional abundance, and this is important to protect for the future, as the Earth changes and warms. Places like Mount Kilimanjaro are betadiverse, I hear, though I have not been.

Haley Melin: ‘Biodiversity II,’ 2024, charcoal, wax and chalk on hand oil-primed linen, 330 x 215 cm // Courtesy of DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM, Berlin, photo by Jens Ziehe

AS: The process of using diverse materials such as charcoal and coffee in your artwork suggests a commitment to sustainability and eco-conscious practices. Can you talk about the relationship between the specific contexts of the paintings (ie. ‘Tree Fall’) and the materials you choose to employ in creating the works?

HM: Ah, this is an easy question. There was a talk on posthumanism recently that affected me and my choice of materials. I use materials that are affordable or freely available (burned charcoal, water) and non-toxic. I try to work with what is on hand rather than buying new materials. A container of paint lasts a very long time and I still have watercolors from the first set of paintings I ever made. At present, my studio has a “buy nothing” policy.

AS: The photorealism that you use in your paintings often blurs the line between reality and idealism. How do you use photorealism to prompt reflection on humanity’s impact on natural habitats and the urgency of conservation action?

HM: I’ve asked conservation mentors how they connect people with caring about conserving land, they always say: “take people there.” I engaged in photorealism in the show here at Dittrich & Schlechtriem, and it took a long time to complete. One of these paintings took about 200-250 hours of time. In this show, the paintings are more realistic to give people a sense of “being there.” I wanted there to be many dots, in a pointillist manner, to show the diverse specks of the nature of a forest, in daylight, over time.

Installing the exhibition, I thought about future ways of painting the same places that may be less realistic, and yet potentially “feel” more like the place. I will likely try this for the next show.

Lastly, you brought up idealism. I am not interested in idealism. Though nature itself can look ideal in some instances, often it does not. One of the beliefs I have in land conservation is to not focus on aesthetics. Don’t conserve a location because it is beautiful, as that is a human-centric notion, and it also limits the widening of our understanding of beauty. If you are a toad living in a mud pit, that mud pit is very beautiful to you since it is your home.

Haley Mellin: ‘Cloud Forrest II,’ 2024, gouache, acrylic, charcoal, and ink on canvas, 40.64 x 40.64 x 3.17 cm // Courtesy of DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM, Berlin, photo by Jens Ziehe

AS: In light of the urgent need to address climate crises and their disproportionate impacts on vulnerable communities, how do you see your role as an artist in advocating for environmental justice and equitable access to safe and healthy habitats?

HM: Since 2017, I have worked on land conservation for the majority of my time. My research and learning for the work began back in 2001 under the mentorship of Dr. John Hurst. Conservation is very important to me, as I find it to be the single most impactful thing I can do with my time. As an artist, it is my work. A painting is a certain expression of art. Land conservation is a certain expression of art. They both have specific aims.

The land conservation work aims to draw a new invisible line on a map that shows what local communities would like to protect. It involves legal diligence, communications and administration to see to it that this line on the map is respected, and that it is as permanent as possible. It is quiet work and when it is done, and a new permanent protected area is declared, nothing has changed on the ground—nature goes on as it has always been.

AS: How does your artistic exploration of “legacy” and “permanence” contribute to the broader conversation about the importance of preserving habitats within the context of environmental conservation?

HM: Both land conservation and art are about legacy, about what we leave behind.

Exhibition Info

Dittrich & Schlechtriem

Haley Mellin: ‘Biodiversity and Betadiversity’

Exhibition: Apr. 24–June 29, 2024

dittrich-schlechtriem.com

Linienstraße 23, 10178 Berlin, click here for map